COMET OF THE WEEK

WEEK 12: MARCH 15-21

THE GREAT COMET OF 1843

Perihelion: 1843 February 27.91, q = 0.006 AU

In addition to being called the “Great Comet of 1843,” this object is sometimes called the “Great March Comet,” and its formal designations are 1843 I (old style) and C/1843 D1 (new style). The earliest reported observation was apparently made on the evening of February 5, with an additional observation on the 11th; unfortunately, there are no details as to who and where (the “source” being a newspaper story at the time), although the comet must have been at least somewhat bright to have been casually noticed and would also have been low in the southwestern sky after dusk.

Normally the orbits of Kreutz sungrazers strongly favor viewing from the southern hemisphere, but this comet came at the right time of the year such that the northern hemisphere was able to obtain decent views as well, at least, after perihelion. Shortly after the beginning of March it began emerging into the evening sky during dusk, and its elongation rapidly increased as it passed closest to Earth (0.84 AU) on March 6, and afterwards. It was a bright object, perhaps around 1st magnitude, when it first appeared, and although it faded as it receded from perihelion, it maintained its brightness rather well, and remained a conspicuous naked-eye object throughout March. The main distinctive feature, meanwhile, of the Great Comet of 1843 was its long, straight, bright dust tail: this was measured as being 35 to 45 degrees long -- with some measurements being as long as 65 degrees -- throughout the entire month.

Although the comet was still a conspicuous object at the end of March, it apparently faded rapidly thereafter. It appears to have dropped below naked-eye visibility just after the first few days of April, and the final observations were reported on April 19.

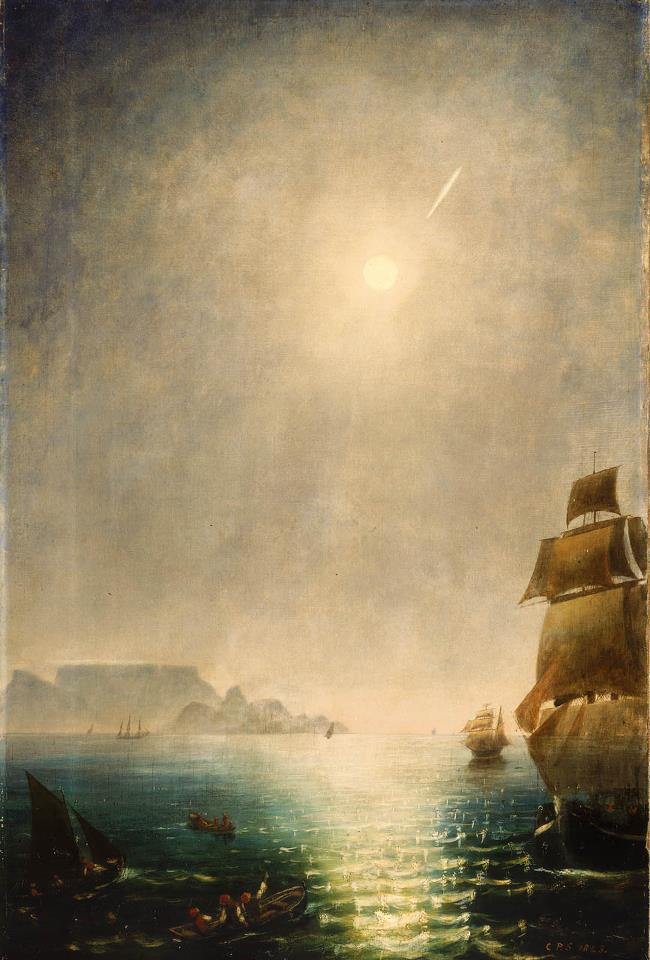

Nighttime views of the Great Comet of 1843. Left: Painting by Charles Piazzi Smith, from eyewitness accounts. The date is unclear, but would have been around March 6, 1843. Right: A painting of the comet around March 23, 1843, attributed to D.A. Hardy. The constellation of Orion is above the comet’s tail to the upper right of center.

Nighttime views of the Great Comet of 1843. Left: Painting by Charles Piazzi Smith, from eyewitness accounts. The date is unclear, but would have been around March 6, 1843. Right: A painting of the comet around March 23, 1843, attributed to D.A. Hardy. The constellation of Orion is above the comet’s tail to the upper right of center.

The comet's long dust tail that was apparent in the nighttime sky was also long in physical terms – over 2 AU. This is the longest cometary tail that has ever been detected optically, although spacecraft observations of Comet Hyakutake C/1996 B2 indicate that its ion tail was even longer; this is next week’s “Comet of the Week.”

“Comet of the Week” archive

Ice and Stone 2020 home page

Earthrise Institute home page