COMET OF THE WEEK

WEEK 42: OCTOBER 11-17

THE GREAT COMET OF 1811

Perihelion: 1811 September 12.76, q = 1.035 AU

Once the orbital calculations for Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1 were made and it appeared that it would be making a “Great Comet” display a year and a half in the future, it was natural for those of us at the time to search for historical analogs. A very good historical analog was the Great Comet of 1811, which – although there is clearly no relationship between the two objects – shares several characteristics with Hale-Bopp, including a high intrinsic brightness, a moderately large perihelion distance, and a rather far distance from Earth. Both comets were visible for a long period of time and both of them were among the brightest and most-observed comets of their respective timeframes.

Although it was never formally named for him, the Great Comet of 1811 was discovered by a French astronomer, Honore Flaugergues, on the evening of March 25 of that year. At that time it was somewhat deep in the southern sky at a declination of -30 degrees in what is now the constellation Puppis, and although located at a heliocentric distance of 2.72 AU and almost six months away from perihelion passage it was already close to naked-eye visibility. By the latter part of May it had brightened to 5th magnitude, although it was also starting to get low in the southwest after dusk, and the last observations before conjunction with the sun were obtained around the middle of June.

After being hidden in sunlight for two months the comet began emerging into twilight around mid-August, already as bright as 2nd or 3rd magnitude. It continued moving northward from that point, and by early September was easily visible from throughout the northern hemisphere as a bright object of 1st or 2nd magnitude with a tail well over ten degrees long.

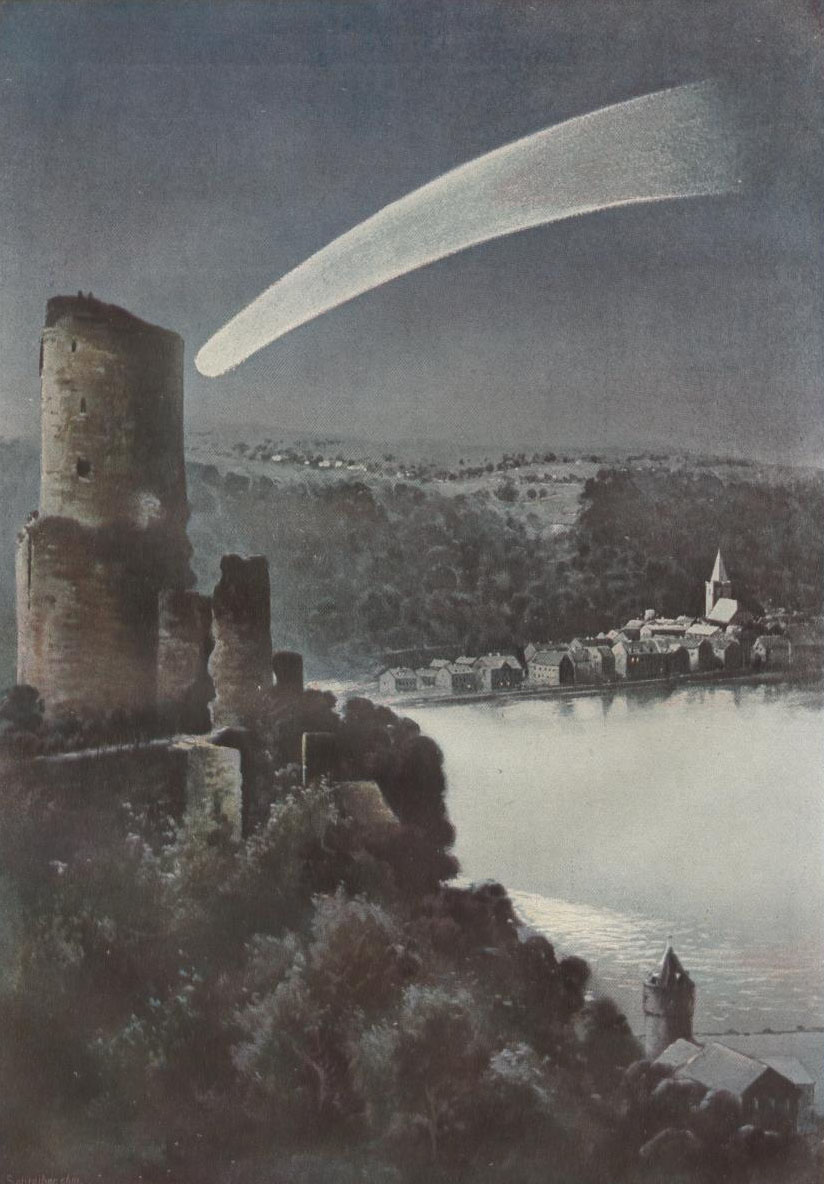

The comet was at its best during early October, when it was a spectacular object high in the northwestern evening sky located south and east of the “handle” of the Big Dipper, as bright as magnitude 1 or 0 with a bright dust tail 25 degrees long or longer. It was closest to Earth on October 16, still at a relatively distant 1.22 AU, and displayed a coma half a degree in diameter -- indicating a physical size larger than the sun. It began a slow fading after that as it traveled southward, although the tail remained moderately long and conspicuous for some time thereafter, and even in December the comet was still 3rd to 4th magnitude and exhibiting a 5-degree-long tail.

The bright and long-lasting appearance of the Great Comet of 1811 seems to have had a profound effect on the non-astronomers of the time. Like other bright comets of the past, it was associated with – perhaps even said to have “predicted” – some of the major historical events that occurred then, such as the series of New Madrid earthquakes that occurred in what is now Missouri in the U.S. during late 1811 and early 1812, as well as wars such as the U.S. War of 1812 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Russia that same year; indeed, in some quarters it was apparently even referred to as “Napoleon’s Comet.” At one point in his novel “War and Peace” – which centers to some extent on Napoleon’s invasion of Russia – Leo Tolstoy has his character Pierre Buzukhov observing this “enormous and brilliant comet,” and this incident is also featured in the 2012 musical production “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812” which is based upon this segment of “War and Peace.” Among other references to the comet in the literature and art of the time, it is apparently featured in the British artist William Blake’s painting “The Ghost of a Flea.”

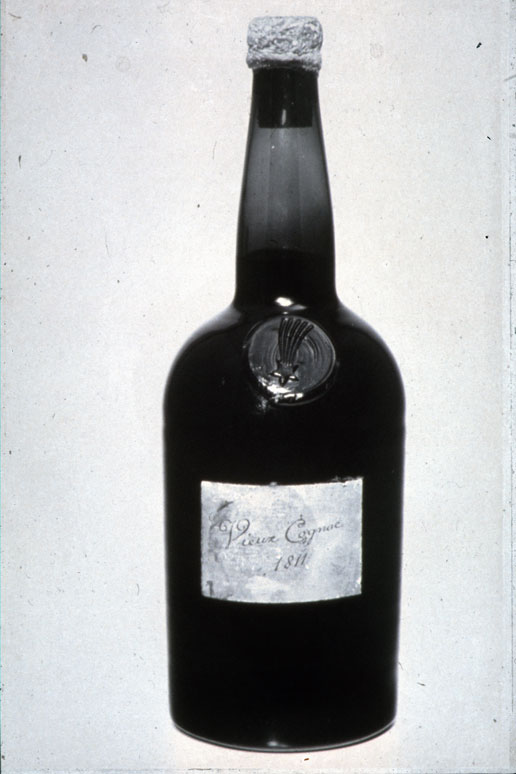

LEFT: “The Ghost of a Flea,” painted by British artist William Blake in 1819-20. The Great Comet of 1811 is apparently represented in the starry background. RIGHT: A bottle of “Comet Wine.” From Patrick Moore's photograph collection.

LEFT: “The Ghost of a Flea,” painted by British artist William Blake in 1819-20. The Great Comet of 1811 is apparently represented in the starry background. RIGHT: A bottle of “Comet Wine.” From Patrick Moore's photograph collection.

The port wine vintage from Portugal and France seems to have been exceptionally good in 1811, and while there is clearly no causal relationship between that and the Great Comet of 1811, the winemakers and merchants of the time realized a good marketing opportunity when they saw one, and “Comet Wine” was sold at high prices for many years thereafter. Like the comet itself, “Comet Wine” from 1811 has also been featured as minor – and sometimes even major – plot elements in several stories, including Ernst Junger’s 1939 novel “On the Marble Cliffs;” one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories (“The Adventure of the Stockbroker’s Clerk”); in one of the stories in the 1986 Isaac Asimov, et al. “Comets” anthology mentioned in a previous “Special Topics” presentation; and even in the 1992 movie “Year of the Comet.” At least one bottle of “Comet Wine” was not opened and tasted until 1996, and in the meantime I am not aware if any other unopened bottles remain.

“Comet of the Week” archive

Ice and Stone 2020 home page

Earthrise Institute home page