COMET OF THE WEEK

WEEK 45: NOVEMBER 1-7

COMET 17P/HOLMES

Perihelion: 2007 May 4.50, q = 2.053 AU

With the light pollution that is endemic to large metropolitan areas, it would seem difficult to believe that any significant astronomical observational activities could be conducted from cities like London these days. But things were different during the late 19th Century . . . On the evening of November 6, 1892, an amateur astronomer in London, Edwin Holmes, was finishing up a night of observations when he decided to finish by taking a look at the Andromeda Galaxy M31. Nearby he happened across a similarly bright (4th magnitude) diffuse object a few arcminutes across . . . which turned out to be a previously-unknown comet.

The sudden appearance of such a bright comet in such a well-observed part of the sky was initially a mystery, but it soon became clear that Holmes’ comet had undergone a massive outburst, presumably of several magnitudes, shortly before its discovery. For the next few weeks it maintained this overall brightness, but the coma expanded dramatically, until shortly before the end of November it was close to 30 arcminutes across. After that it began a rapid fading, and by the end of the year it was close to 10th magnitude, however in mid-January 1893 it underwent another outburst of at least five

Holmes’ comet was found to be periodic, with an orbital period of close to seven years. It was duly recovered in 1899 but remained faint, never getting brighter than 13th magnitude, and was even fainter in 1906, when it only reached 15th magnitude and was only photographed on a handful of occasions. After that it was missed on the next several subsequent returns, and the general consensus was that it had disintegrated – the major outbursts in 1892-93 perhaps having been its death throes. However, in his landmark 1963 study on “lost” periodic comets – already mentioned in the “Comet of the Week” Presentation of Comet 9P/Tempel 1 – then-Yale University graduate student Brian Marsden analyzed the motion of Comet Holmes, and determined that it should be returning to perihelion in November 1964. Elizabeth Roemer, then at the U.S. Naval Observatory’s station in Flagstaff, Arizona, successfully photographed it in July and September of that year as a very faint object of 19th magnitude, verifying that the comet indeed still existed.

Comet Holmes was duly recovered at each of the next several subsequent returns, and remained a faint and entirely unremarkable object never getting any brighter than 17th or 18th magnitude. When it was recovered in May 2007 around the time of that return’s perihelion passage it was somewhat brighter, around 15th magnitude, but faded steadily from that point, and by September and October was back around 17th magnitude.

On October 24 a Spanish astronomer from near Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Juan Antonio Henriquez Santana, reported that the comet was apparently undergoing a massive outburst and was close to 8th magnitude, which was quickly verified by other Spanish observers (who reported it as having brightened to 7th magnitude). After reading their report a few hours later I observed it as a star-like object of 4th magnitude, and within about half a day it had reached close to its peak brightness of almost 2nd magnitude. It was obvious that the comet was experiencing an outburst similar to that of 1892, and the overall brightness change of almost 15 magnitudes, corresponding to an increase in brightness by a factor of approximately 600,000, is the largest cometary outburst ever recorded.

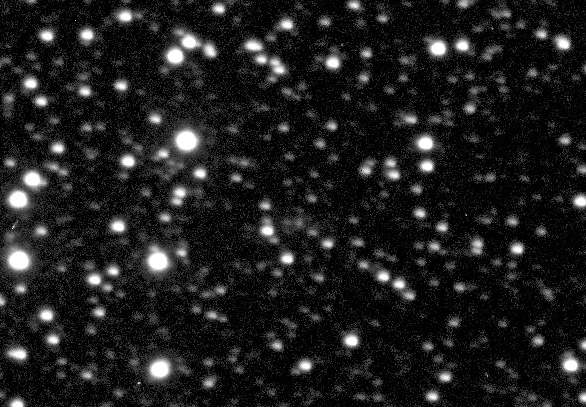

The early stages of Comet Holmes’ 2007 outburst. Left: Image taken on October 24 -- shortly after the outburst began -- by Ernesto Guido and Giovanni Sostero in Italy, utilizing a remotely-controlled telescope in New Mexico. Right: The comet on October 29. Courtesy Mike Holloway in Arkansas.

The early stages of Comet Holmes’ 2007 outburst. Left: Image taken on October 24 -- shortly after the outburst began -- by Ernesto Guido and Giovanni Sostero in Italy, utilizing a remotely-controlled telescope in New Mexico. Right: The comet on October 29. Courtesy Mike Holloway in Arkansas.

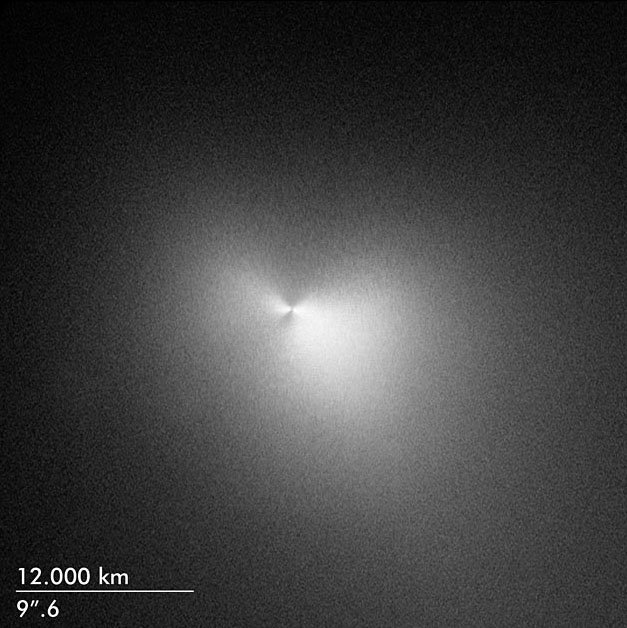

The evolution of the new outburst was similar to that of 1892; within a week the comet appeared as a dense inner coma about 15 arcminutes across enshrouded within a dimmer outer “halo” half a degree in diameter, and within another week this “halo” was almost a full degree across. By December this “halo” had all but dispersed, however the inner coma itself expanded, being over a degree across by late in the year. The comet itself slowly faded, being close to 4th magnitude in late December and 5th magnitude in March 2008, by which time the coma was only dimly detectable to the unaided eye as a pale diffuse cloud about 80 arcminutes in diameter. The entire comet exhibited numerous features over both large scales and small scales, from strong jets off the nucleus that were visible in images taken with the Hubble Space Telescope, to “streamers” within the coma which itself took on a “bow in a wake” appearance, and to faint streams of an ion tail, which was mostly directed away from Earth.

LEFT: The inner coma of Comet Holmes on November 4, 2007, as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Courtesy NASA. Right: A wide-field image of Comet Holmes I took on the evening of December 2, 2007. The Alpha Persei Cluster (Melotte 20) is below the comet.

LEFT: The inner coma of Comet Holmes on November 4, 2007, as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Courtesy NASA. Right: A wide-field image of Comet Holmes I took on the evening of December 2, 2007. The Alpha Persei Cluster (Melotte 20) is below the comet.

Several possible explanations for Comet Holmes’ outburst activity have been proposed. One of these held that the 2007 outburst might have been due to a companion nucleus being jettisoned from the primary nucleus and then undergoing a “cataclysmic” disintegration. Another explanation proposed that the outburst was due to an airtight dust cover over the nucleus that was broken up by water sublimation going on underneath it. In truth, no explanation seems entirely satisfactory, given the unique nature of the outbursts in both 1892-3 and in 2007, and the fact that while other comets have clearly exhibited outbursts, those of Comet Holmes are pretty much in a class by themselves.

Later stages of Comet Holmes’ 2007 outburst. Left: The comet on November 28, 2007. The coma’s parabolic shape and the “wake”-like structure in the inner coma are prominent. Right: Comet Holmes and the California Nebula (NGC 1499) on the evening of March 4, 2008. Both images courtesy Mike Holloway in Arkansas.

Later stages of Comet Holmes’ 2007 outburst. Left: The comet on November 28, 2007. The coma’s parabolic shape and the “wake”-like structure in the inner coma are prominent. Right: Comet Holmes and the California Nebula (NGC 1499) on the evening of March 4, 2008. Both images courtesy Mike Holloway in Arkansas.

After the 2007 outburst subsided large telescopes continued to follow the comet, through its aphelion in late 2010. At its next return in 2014 (perihelion late March) it underwent a couple of small outbursts, to magnitude 12½ in late May/early June and another one to about magnitude 14½ in late January 2015 -- ten months after perihelion passage -- but nothing close to what it underwent in 2007. It has now been picked up en route to its next perihelion passage on February 19, 2021 and, not unexpectedly, has thus far remained rather faint (currently about 17th magnitude). Meanwhile, it should be returning every seven years hearafter for at least the near-term foreseeable future; perhaps some day it may burst forth yet again in another major outburst, and maybe at that time we might be able to determine just what is causing this bizarre behavior.

“Comet of the Week” archive

Ice and Stone 2020 home page

Earthrise Institute home page