TALLY ENTRIES 651-660

We have known for some time that the difference, in physical terms, between "comets" and "asteroids" is rather nebulous (and there is admittedly a pun in saying this). Indeed, that awareness began almost a century ago, when in 1920 the German astronomer Walter Baade (who, two to three decades later after relocating to southern California, would become one of the pioneers in the study of stellar populations) discovered an apparently asteroidal object with an orbital period of just under 14 years, a perihelion distance close to 2 AU, and an aphelion distance almost as far out as Saturn's orbit. Despite careful scrutiny over several subsequent returns, this object -- now known as (944) Hidalgo -- has never exhibited any clear signs of cometary activity, although there is nevertheless a moderately strong consensus among cometary astronomers that it is an extinct cometary nucleus. I managed to observe Hidalgo during its returns in 1991 and 2005, and I have just now picked it up on an additional return; it will pass through perihelion in late October 2018 and should reach 14th magnitude.

During the decades that have elapsed since Hidalgo's discovery many additional apparent asteroids in distinct cometary orbits have been discovered, and the consensus is that many, if not almost all, of these objects are also extinct (or perhaps dormant) cometary nuclei. Indeed, the late planetary scientist Eugene Shoemaker once estimated that, for every active Jupiter-family comet, there may be as many as eighteen to twenty extinct Jupiter-family comets. It is conceivable that some of these objects might still exhibit weak cometary activity on occasion, and I do attempt to observe any which become bright enough for visual observations (partially in the hope that I might be able to add them to my tally retroactively). The classic case is (3552) Don Quixote, originally discovered in 1983 and which has a perihelion distance of approximately 1.2 AU and an orbital period of slightly under nine years. During its 2009 return (during which I managed to observe it on two occasions as a stellar 15th-magnitude object) the infrared-sensitive Spitzer Space Telescope detected a weak coma and tail; when this was announced some years later I retroactively added Don Quixote to my tally (no. 562). During its return earlier this year Don Quixote once again exhibited weak cometary activity.

Over the past decade or so another type of object has demonstrated the "nebulous" boundary between "comet" and "asteroid." There are the objects once called "main belt comets" but now more generally known as "active asteroids." As these terms suggest, these are objects that travel in low-eccentricity (and low-inclination) orbits like those of asteroids in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, but which have on one or more occasions exhibited some type of cometary activity. Some of these objects -- for example, the object now designated as 133P/Elst-Pizarro -- have exhibited such activity on several occasions and it appears to be genuinely due to water-ice sublimation just as in more "traditional" comets. However, other mechanisms seem to be responsible for the activity in other objects. Some of these have nevertheless been formally designated as short-period comets; the activity in 311P/PANSTARRS has been apparently due to dust clouds ejected by a very rapid sunlight-driven rotation, while the activity in 354P/LINEAR was apparently due to debris created by an impact from a smaller asteroid.

In December 2010 the large main-belt asteroid (596) Scheila exhibited a comet-like coma and tail that were very likely caused by an impacting smaller asteroid. I have been observing Scheila on a semi-regular basis ever since that occasion, and it has never exhibited any repeat of that activity; nevertheless, after the official designation of "Comet" 354P/LINEAR last year I retroactively added Scheila to my tally (no. 623), as I explain in its entry. Following Scheila's aphelion in late 2014 I have continued to follow it from time to time (no. 624), and it is presently near opposition and close to magnitude 13.5.

Another large main-belt asteroid has now been seen to exhibit a one-time burst of cometary activity. This is (493) Griseldis, originally discovered from Heidelberg Observatory in Germany in September 1902 by the German astronomer Max Wolf, and which is about 46 km (29 miles) in diameter and which has an orbital period of 5.5 years. (Wolf was one of the top astronomers of his era and pioneered the then-emerging art of astrophotography; during a career that spanned four decades in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries he discovered almost 250 asteroids -- a record for the time -- and three comets, two of which are short-period comets and one of which, 43P/Wolf-Harrington, I've observed on five returns. He has the distinction of recovering (in September 1909) Comet 1P/Halley during its 1910 return.) The name "Griseldis" is a feminine personification of the quality of virtue, and appears in some medieval and classical novels and operas.

On March 17, 2015, astronomers Dave Tholen, Scott Sheppard, and Chad Trujillo detected a short tail on Griseldis in images taken with the 8.2-meter Subaru Telescope located on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. Additional images obtained with one of the twin 6.5-meter Magellan Telescopes (based at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile) four nights later also show this feature, albeit weaker, but it has not been detected on any subsequent images. At the time these images were taken Griseldis was a little over 1 1/2 years past its perihelion passage (and thus slightly closer to aphelion), and in light of all the available evidence Tholen and his colleagues have concluded that the activity Griseldis exhibited is very probably the result of an impact event, just as was the case with Scheila.

Based upon the precedent I established with Scheila, I have concluded that I am justified in including Griseldis as a comet for tally purposes. It was at opposition in early July 2017 and I made one unsuccessful attempt for it in late June of that year; while it was probably too faint for me to detect then, its location within rich Milky Way star fields didn't help. During its present period of visibility I made my first attempt for it on the evening of September 8 and successully detected it as a stellar object of magnitude 14 1/2 that exhibited distinct motion over an interval of an hour.

At present Griseldis is located in south-central Pisces some three degrees west of the star Delta Piscium and is traveling almost due westward at just under 15 arcminutes per day. It is at opposition at the very beginning of October when it should be a few tenths of a magnitude brighter than it is now, and I should be able to follow it until sometime in November (when it will be located some 1 1/2 degrees north of the star Omega Piscium), at which time it should fade beyond my range. Following its perihelion passage next February it is in conjunction with the sun during the latter part of May; meanwhile, it is possible it may be just bright enough for me to detect around the time of the next opposition in early February 2020, at which time it will be located in southern Lynx. I do not expect Griseldis to exhibit any repeat of its previous cometary activity during this time, although I suppose the possibility exists that I could be pleasantly surprised.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 September 9.24 UT, m1 = 14.5, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (October 2, 2019): Following conjunction with the sun this past May, Griseldis has now emerged into the morning sky, and according to recent CCD observation reports I have seen it is currently around 16th magnitude, about where it should be. I remain cautiously optimistic that I'll be able to observe it visually around the time of its next opposition in early February 2020.

On October 30, 2019, Griseldis is predicted to occult the 6th-magnitude star HD 77660 in northeastern Cancer (located 45 arcminutes east of the star 66 Cancri). The occultation, which should occur between 7:32 and 7:38 UT, will last a maximum of 2.6 seconds and will feature a drop in the star's brightness of almost 10 magnitudes. The current predicted path of the occultation crosses northwestern Mexico, the central U.S. from Texas to Michigan, and southeastern Canada. (For what it's worth, my home location is 200 km northwest of the predicted path, and McDonald Observatory, where one of the nodes of the Las Cumbres Observatory is located, is less than 90 km southeast of the center of the path and is just outside the formal region of uncertainty.)

UPDATE (January 19, 2020): Griseldis is now less than two weeks away from being at opposition at the beginning of February, and I successfully picked it up on the evening of January 18 as an extremely faint, stellar object of 15th magnitude. It is currently located in southeastern Lynx four degrees northwest of the star Alpha Lyncis and is traveling westward at slightly under 15 arcminutes per day; it is probably as bright as it is going to get during this opposition season, and should maintain its present brightness for another couple of weeks before starting to fade. I hope to observe it another time or two before it fades beyond my range.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 January 19.16 UT, m1 = 15.1, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

652. COMET ATLAS C/2018 L2 Perihelion: 2018 December 2.58, q = 1.712 AU

Another ATLAS-discovered comet enters my tally. This one was discovered by the Mauna Loa telescope on June 6, 2018, and was reported as being around magnitude 15 1/2 to 16 -- rather bright for a survey discovery these days. Although it was located fairly far south at a declination of -42 degrees, it was otherwise accessible without much difficulty from my observing site, but my visual attempt for it a few days after its discovery was unsuccessful. I did, however, successfully image it with the Las Cumbres Observatory telescope at Siding Spring while it was still listed on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page.

The comet is traveling in a moderately high-inclination (67 degrees) direct orbit and, having already passed through opposition in early May, has remained in the evening sky ever since its discovery while steadily climbing northward. Due in significant part to our summer monsoon as well as to the health issues I described in an earlier entry, I did not attempt it again until early September, by which time its declination had reached -8 degrees. I possibly saw "something" during my first attempt, but it was located in a very poor star field and I couldn't convince myself that I was actually seeing anything. Finally, on the evening of September 10 -- when it was located in a better star field -- I clearly saw the comet as a diffuse, slightly condensed object just a bit fainter than 13th magnitude.

This more recent Comet ATLAS is presently located fairly low in my southwestern sky after dusk, in northern Libra some five degrees northwest of the star Beta Librae, and is traveling towards the east-northeast at slightly less than half a degree per day. Despite the fact that it is still 2 1/2 months away from perihelion passage and is continuing its northward climb, I will probably not be able to obtain many observations of it; it was closest to Earth (1.95 AU) in mid-June and is now moving over to the far side of the sun, and accordingly will be sinking lower and lower into the western sky. At present its elongation is 50 degrees, with this decreasing to 40 degrees in early October and reaching a minimum of 32 degrees in mid-November. By that time it will be in near-conjunction with the sun (although well to the north of it), where it will remain well into 2019, with the actual moment of conjunction coming in mid-January, when it will be 45 degrees north of the sun and located in Vulpecula. The elongation reaches a maximum of only 47 degrees in mid-February (while passing directly across the central portions of the Veil Nebula in Cygnus during the first week of that month) before shrinking again, reaching a minimum of 35 degrees in mid-May -- before which time it passes some four degrees north of the Andromeda Galaxy M31 shortly after mid-April -- and then it finally begins to increase again. I suspect the comet will be long past the point of visual detectability by then; while it might reach perhaps 12th magnitude around the time of perihelion, it will likely fade beyond visual range within one to two months after the beginning of 2019.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 September 11.11 UT, m1 = 13.3, 1.2' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

653. COMET 46P/WIRTANEN Perihelion: 2018 December 12.94, q = 1.055 AU

In one of my tally entries from a year ago I commented that, ever since I relocated to 16 Springs Canyon in 1995, I have managed to add at least one comet to my tally during the month of September every year. I have now continued that remarkable string for the 24th consecutive year, and indeed did so in rather dramatic fashion by adding three comets to my tally over a span of only four nights during this month of September 2018. And there is still a bit of September left to go, although with the upcoming full moon -- the Harvest Moon, in fact, with its long series of bright moonlit evenings -- and no strong candidates for tally additions at this time, I doubt if I'll add any more comets before month's end.

The third comet of this "trio" is an old friend that I am now seeing for the sixth time. I observed it during its 2008 return (no. 416) as a part of "Countdown" and I discuss its observational history, and my own history with it, in its "Countdown" entry. As I predicted there, the intervening return in 2013 was very unfavorable and I did not look for it, but it is now back for the best return it will ever make. It was recovered on June 18, 2018 by a team led by Lori Feaga from the University of Maryland while utilizing the Discovery Channel Telescope based at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. (An earlier apparent recovery on May 8 reported by members of the same team turned out to be a false alarm, as the "comet" turned out to be a faint main-belt asteroid that, coincidentally, was located close to P/Wirtanen's expected position and that exhibited its expected motion. Once this was recognized, the comet -- fainter than expected -- was belatedly recognized on the same images.) I made my first attempt for it in early September but didn't see anything convincing, however on the morning of September 12 I successfully observed the comet as a small, diffuse object of 14th magnitude. It has brightened rapidly since then, by over half a magnitude when I observed it again six mornings later.

On December 16 Comet P/Wirtanen passes only 0.077 AU from Earth -- the eighth-closest approach to our planet of all the comets on my tally. (Curiously, this encounter takes place exactly one year, to the very day, after the seventh-closest approach to Earth of the comets on my tally.) Because of this close approach and the accompanying very favorable viewing circumstances, the comet is the target of a special NASA-coordinated observing campaign during this return. I am involved with this campaign and will be contributing both visual observations as well as images taken with the Las Cumbres Observatory network -- indeed, I have already obtained one such image, taken about two weeks ago -- and possibly some DSLR photographs. Although I am not quite to the point where I am working with students yet, it is conceivable that I might have some working with me by the time of the close approach to Earth.

At present Comet 46P/Wirtanen is located in southern Cetus three degrees southwest of the star Upsilon Ceti (and some seven degrees south of the nearby solar-type star Tau Ceti). It is traveling towards the southeast at a present rate of 20 arcminutes per day, crossing into northwestern Fornax within a few days and being at opposition during the third week of October, when its declination will be -31 degrees. After reaching a peak southerly declination of -33 degrees in early November the comet begins a rapid climb to the north-northeast, back into Cetus and then into Eridanus and (during the second week of December) Taurus. At the time of its closest approach to Earth it will be located four degrees southeast of the Pleiades star cluster (M45) and will be traveling (still towards the north-northeast) at a little over four degrees per day. Based upon the brightness I've observed during previous returns, it may be 11th to 12th magnitude during October, brightening from 10th to 9th and possibly 8th magnitude during November, and could well be a naked-eye object of 4th or 5th magnitude (but with a very large, diffuse coma) around the time of its closest approach.

Following it passage by Earth the comet continues its rapid north-northeast climb, crossing into Perseus, Auriga (passing one degree southeast of the bright star Capella on December 23), and Lynx, where it will be located when it goes through opposition again just before the end of December. Having slowed down to one degree per day (and continuing to decrease), it reaches its farthest north point, declination +59.5 degrees, during the second week of January 2019, at which time it crosses into western Ursa Major. The comet then begins dropping towards the south-southeast, being at opposition yet again in mid-February (by which time its motion will have decreased back to 20 arcminutes per day) and then crossing into Leo Minor in mid-March and into north-central Leo around mid-May. While it may still be as bright as 7th or 8th magnitude at the beginning of January, I expect that it will fade fairly rapidly, perhaps to 11th magnitude during February, and I will probably lose it by sometime in March.

This is quite probably the last return during which I will observe Comet P/Wirtanen, although it is certainly going out with a "bang!" With its current orbital period of 5.4 years the next return (perihelion May 2024) is very unfavorable, while the return after that (perihelion October 2029) is reasonably good. The comet has another decent return in 2040 (perihelion early October), during which time I would be 82 years old. After that a pair of close approaches to Jupiter will conspire to keep it unfavorably placed for quite some time, and not until 2066 is there even a moderately decent return, however by that time its perihelion distance will have increased to 2.0 AU and its orbital period will have increased to 7.3 years. Even the 2029 return is after the "retirement" timeframe I have discussed in previous entries, although I suppose time will tell.

Meanwhile, I am continuing my recovery from the health issues I experienced a few months ago, although I still have quite a ways to go. I am happy to say that I am more-or-less back to my regular observing activity, and I have started working out again on a limited basis. My biggest priority right now is fundraising so that Earthrise can carry out the activities and fulfill the vision that I have described elsewhere on this web site. Perhaps the observations I will be making of Comet P/Wirtanen during this unique return and my involvement in the observing campaign will help towards that end.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 September 12.35 UT, m1 = 13.9, 0.6' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (November 20, 2018): Comet P/Wirtanen has brightened rapidly since I first picked it up, and by mid-November was easily detectable in binoculars as a large diffuse cloud half a degree in diameter and 7th magnitude. The moon has interfered since then, however according to observers in the southern hemisphere (who, for the time being, can see it much higher in their sky and could continue observing it after moonset) it has now reached the point where it is flirting with naked-eye brightness. At this writing it seems quite likely that the comet will be an easy naked-eye object when it is closest to Earth next month.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 November 14.23 UT, m1 = 6.8, 32' coma, DC = 4 (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (November 29, 2018): By the time the moon had cleared out of the evening sky in late November Comet Wirtanen had reached naked-eye visibility at 6th magnitude, and in binoculars was displaying a large and slightly condensed coma over half a degree in diameter. At this point I would predict a peak brightness somewhere around 4th magnitude when it is nearest Earth in mid-December.

I took this "camera-on-tripod" DSLR photo on the evening of November 27, at which time the comet was located 0.134 AU from Earth.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 November 28.11 UT, m1 = 5.9, 36' coma, DC = 4 (10x50 binoculars)

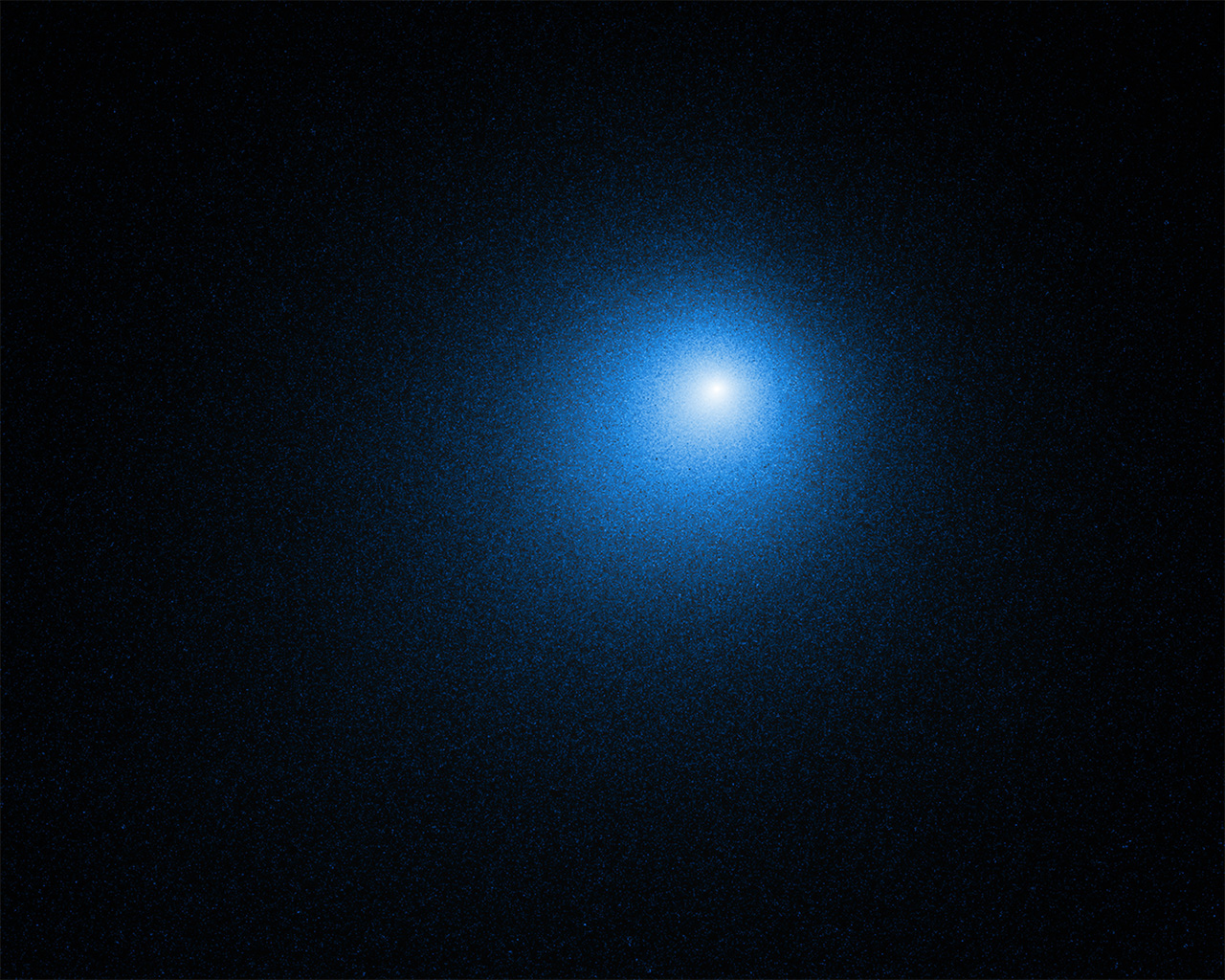

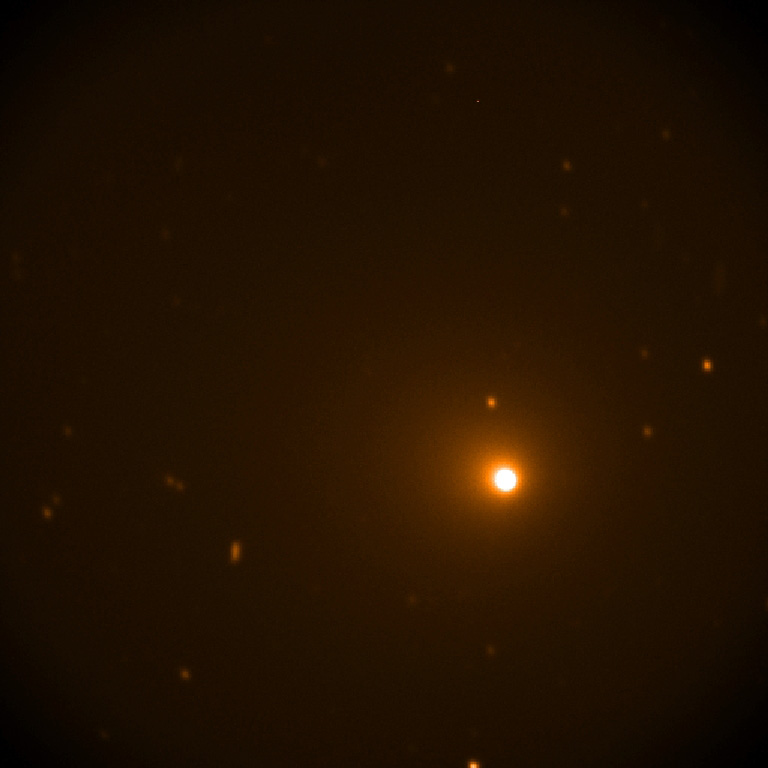

A recent NASA press release exhibits images of Comet 46P taken by the Hubble Space Telescope on December 13 (left) and with the visible-light guide telescope of the airborne infrared SOFIA observatory on December 16 and 17 (right). (Both images courtesy NASA.)

When nearest Earth Comet 46P became as bright as 4th magnitude and exhibited a naked-eye coma up to 1 1/2 degrees in diameter. At this writing the full moon is interfering with observations, although once the moon clears from the evening sky the comet will again be easily observable. Now that it is receding from the sun and Earth it should be fading, although it should remain visible to the unaided eye for perhaps another two to three weeks.

BRIGHTEST OBSERVATION: 2018 December 14.21, m1 = 3.9, 1.6 degree coma, DC = 3-4 (naked eye)

654. COMET 78P/GEHRELS 2 Perihelion: 2019 April 2.76, q = 2.014 AU

At the beginning of the previous entry -- my third tally addition during the month of September 2018 -- I commented that I probably would not be adding any more comets to my tally that month. It turns out that September wasn't quite finished with me after all . . . And as I commented at the end of this particular comet's "Countdown" entry for its 2012 return (no. 492), its current return is rather unfavorable, and I never expected to look for it, let alone observe it. However, once the Harvest Moon had cleared out from the evening sky the last few nights of September were very clear -- a situation which changed shortly after the beginning of October when moisture from the remnants of Hurricane Rosa flowed into the area, bringing clouds and rain -- and after seeing some recent CCD images and brightness measurements that suggested the comet might be worth attempting, I decided to try for it on the evening of the 29th -- and was rather surprised when I saw a very dim and diffuse but nevertheless distinct 14th-magnitude object at the correct position. I successfully observed the comet again on the following night.

On this time around P/Gehrels 2 was recovered on May 15, 2018 by Japanese amateur astronomer Toshihiko Ikemura, and independently a day later by the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona. It went through opposition just after mid-August and at present is located in western Aquarius four degrees southwest of the star Beta Aquarii, where it will go through its stationary point during the first week of October and resume direct (eastward) motion. After traveling through northeastern Capricornus the comet crosses back into Aquarius during late November, and continues traveling east-northeastward through that constellation -- passing some six degrees south of the "water jar" in late December -- before entering Pisces during the second week of January 2019, where it remains until it disappears into the dusk a month and a half or so later. I don't expect much change in brightness -- at most, a slight brightening of a few tenths of a magnitude -- during this period, and to be truthful I doubt if I'll be getting more than a handful of observations of it.

In its "Countdown" entry I noted that P/Gehrels 2's return in 2026 is also quite unfavorable, although it might potentially be bright enough for visual observations in the morning sky after its perihelion passage in late June of that year. As I have commented in several previous entries, however, that is after my currently-planned "retirement" from visual comet observing, so, I suppose we'll see . . . In any event, my days of observing this comet are numbered regardless of whether or not I see it in 2026; its "Countdown" entry mentions the close approach to Jupiter in 2029 and the subsequent much larger orbit, and another close approach to Jupiter in 2046 increases the perihelion distance even further to 5.1 AU and the orbital period to approximately 40 years.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 September 30.13 UT, m1 = 14.1, 1.0' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

655. COMET MACHHOLZ-FUJIKAWA-IWAMOTO C/2018 V1 Perihelion: 2018 December 3.51, q = 0.387 AU

It has been over eight years since there had been a comet visually discovered by amateur astronomers (Comet 332P/Ikeya-Murakami P/2010 V1 (no. 481)), and I honestly felt that those days were probably gone forever. While I knew of a few would-be comet discoverers who were still sweeping the skies for comets, with all the automated surveys that are operating nowadays I considered it very unlikely that any of these individuals would ever meet with success.

But I am very happy to be proven wrong! On the morning of November 7, 2018, my friend Don Machholz in California -- although he plans to relocate to Arizona by the end of this year -- visually discovered his 12th comet, which he reported as being about 10th magnitude. I had seen Don this past May when my girlfriend Vickie and I attended the 50th anniversary Riverside Telescope Makers' Conference, and he told me then that he still continued to hunt for comets regularly. He reports that when he found his latest comet he had completed almost 750 hours of visual comet hunting since his previous discovery (Comet Machholz C/2010 F4 (no. 471)).

A few hours after Don's discovery, two Japanese amateur astronomers who are also veteran comet discoverers, Shigehisa Fujikawa and Masayuki Iwamoto, independently discovered the same comet; both of them were using CCDs when they made their respective discoveries. Fujikawa visually discovered six comets between 1969 and 2002 (as well as two more in 1968 for which his reports were too late for him to receive credit); I successfully observed three of these, Mori-Sato-Fujikawa 1975j (no. 18), Sugano-Saigusa-Fujikawa 1983e (no. 58) (which passed 0.06 AU from Earth in June of that year), and Kudo-Fujikawa C/2002 X5 (no. 324). (Another one of his discoveries is the sometimes-lost, sometimes-found periodic Comet 72P/Denning-Fujikawa, which I've searched for unsuccessfully on two returns, most recently in 2014.) Iwamoto has one previous comet discovery to his credit, Comet Iwamoto C/2013 E2 (no. 522).

According to the preliminary orbit calculation available at this writing, the comet is traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 144 degrees). It had been hidden in sunlight for a few months, being in conjunction with the sun in late August, and has only recently emerged into the morning sky. I learned of the comet's discovery on the 8th and unfortunately was clouded out the following morning; the morning after that -- the 10th -- was clear, however, and Vickie and I successfully observed it as a relatively condensed object low in the eastern sky in the zodiacal light. The comet was bright enough that I could dimly detect it in 10x50 binoculars as a faint, slightly fuzzy "star" near magnitude 9 1/2, and through the 41-cm telescope I could perhaps just barely see the beginnings of a faint westward-pointing tail.

At the time of its discovery the comet was right at its maximum elongation from the sun of just under 40 degrees. At this writing its elongation is still 39 degrees, being located in central Virgo 1 1/2 degrees east of the star Gamma Virginis (Porrima); presently it is traveling almost due eastward at 1 1/2 degrees per day, but this accelerates over the coming days as the elongation rapidly starts to decrease. This drops below 30 degrees on November 21 (with the corresponding motion being 3 1/2 degrees per day) and below 25 degrees three days later (the motion having by then increased to over 4 degrees per day). The comet is nearest Earth (0.67 AU) on November 27 and is in inferior conjunction with the sun (18 1/2 degrees north of it) two days later.

If the comet survives its relatively close perihelion passage it should emerge into evening twilight near the end of the first week of December, when it will be located in Serpens Cauda and traveling towards the east-southeast at a little over two degrees per day (although this rapidly decreases over the subsequent weeks). The elongation reaches a maximum of just over 24 1/2 degrees on December 10 and 11 (during which time the comet is traveling through Scutum) but then steadily decreases, dropping below 20 degrees on December 21. The comet is again in conjunction with the sun (6 degrees south of it, and on the far side as seen from Earth) shortly after mid-January 2019 and begins to emerge into the southern hemisphere's morning sky towards the end of February.

I have not seen the comet since my initial sighting on the morning of the 10th, however I have read reports from other observers that suggest it may be brightening rather rapidly. This would not seem to be too surprising, especially if the comet has become active relatively recently; furthermore, the viewing geometry over the next three weeks or so is quite favorable for brightness enhancement due to forward scattering of sunlight (even though the small elongation will preclude easy viewing of it). If such a brightness trend continues, then the comet may be as bright as 7th magnitude, or even brighter, by the time it is lost in twilight towards the end of November, and -- provided it survives perihelion passage -- it could be as bright as 5th or 6th magnitude during its brief evening-sky appearance in December (although the small elongation will probably keep it from being detectable with the unaided eye). It will likely be quite faint -- quite possibly beyond the range of visual detectability -- when it emerges into the morning sky next year.

The appearance of this surprise comet -- that has the potential of becoming at least somewhat bright -- and its reassurance that the days of visual comet discoveries are not entirely over yet comes at a time when there should be some interesting occurrences in my life within the not-too-distant future. I'll write more about these in future entries . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 November 10.49 UT, m1 = 9.4, 2.5' coma, DC = 5-6 (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (November 20, 2018): I have observed this comet fairly frequently ever since I first picked it up, and it has brightened -- although perhaps not by as much as to give a sense of optimism for a bright display next month. I obtained what will probably be my last pre-perihelion sighting this morning, and in twilight it appeared as a moderately condensed -- although less so than it was initially -- object of approximate magnitude 8 1/2. With the full moon now imminent and the comet's elongation (presently 31 degrees) rapidly decreasing, I probably won't be able to look for it again until its evening-sky appearance in December -- provided, of course, that it survives perihelion passage.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 November 20.52 UT, m1 = 8.5:, 4' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (December 10, 2018): The comet did survive perihelion passage, and for the past week or so has been visible low in the southwestern evening sky during dusk; it is not bright, however, with most observers reporting it at somewhere between 9th and 10th magnitude. After some cloudy nights I successfully saw it on the evening of December 8 as a diffuse but somewhat condensed object near magnitude 9 1/2. It is already at its maximum elongation of 24.7 degrees, and thus over the coming days it will sink back deeper into twilight, and also should be fading as it recedes from the sun and Earth; with the moon now entering the evening sky I suspect that I am almost certainly finished with this comet.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2018 December 9.05 UT, m1 = 9.5, 2.7' coma, DC = 3 (20 cm reflector, 47x)

656. COMET 60P/TSUCHINSHAN 2 Perihelion 2018 December 11.23, q = 1.623 AU

In my tally entry for last year's return of Comet 62P/Tsuchinshan 1 (no. 630) I discuss the discovery of two periodic comets from China's Tsuchinshan, or Purple Mountain, Observatory in January 1965. As I discuss in that entry, I have now successfully observed the first of these (62P) on four returns, but had at that point unsuccessfully attempted the second one (60P) on three returns (those of 1992, 1999, and 2005). As I also mention there, I considered it possible that I might end that string of non-successes this year, thanks to a close approach to Jupiter a decade ago (0.33 AU in December 2008) and the resulting decreased perihelion distance (from the previous 1.77 AU), together with favorable viewing geometry. That possibility has now become a reality.

The comet was recovered on September 6, 2018 by amateur astronomer Denis Buczynski -- the current Secretary of the Comet Section of the British Astronomical Association -- at his private Tarbatness Observatory in Portmahomack, Scotland. Reported as being about 18th magnitude at that time, it has brightened steadily since then, and various CCD images I have seen have shown it as a small condensed object with a distinct dust tail. After one unsuccessful attempt earlier in November I successfully picked it up on the morning of November 16; it appeared as a very faint, small, and moderately condensed object of 14th magnitude that exhibited distinct motion over a half-hour interval. The appearance was similar -- perhaps just marginally brighter -- when I observed the comet again four mornings later. I could not see any sign of the tail -- this being too faint for me to pick up visually -- but it does show up well on a Las Cumbres Observatory image that I took on the morning after my initial sighting.

At present the comet is located in western Leo some two degrees southwest of the bright star Regulus, in the morning sky at an elongation near 90 degrees. It is traveling towards the east-southeast through the southern regions of that constellation (albeit spending a little over a week in northeastern Sextans in early December) before crossing into western Virgo in mid-January 2019; after reaching its stationary point in early February it turns back towards the west-northwest, crossing back into Leo in early March and being at opposition during the middle of that month. It subsequently spends the next several weeks within that constellation, passing through its other stationary point in mid-April before heading back eastward again.

Since there apparently is no visual brightness data for Comet 60P from any previous returns -- and certainly none with the current perihelion distance -- it is difficult to predict just what to expect in terms of brightness. With its perihelion passage shortly before mid-December and its closest approach to Earth (0.83 AU) during the latter part of February it would seem reasonable to expect some brightening over the coming weeks, perhaps by up to a magnitude or so. It will then likely fade beyond the range of visual detectability by sometime in March.

The comet will maintain something close to its present perihelion distance and present orbital period (6.6 years) up until another somewhat close approach to Jupiter in 2068. There aren't any especially favorable returns coming up anytime soon; the next return, in 2025 (perihelion late July), is very unfavorable, while the one after that, in 2032 (perihelion early March), is somewhat favorable, although slightly inferior to the present one. With the potential "retirement" timetable that I have discussed in previous entries, it would seem rather likely that the current return is the only one I will ever observe for this comet -- but after all my previous unsuccessful attempts it is nice that I am finally able to view it this time around before all is said and done.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 November 16.47 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.4' coma, DC = 6-7 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

657. COMET ASASSN C/2018 N2 Perihelion: 2019 November 10.96, q = 3.125 AU

The All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN) program recorded its second comet discovery on July 7, 2018, slightly less than a year after its first discovery (no. 626) -- both discoveries having been made by the survey's telescope located at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. At its discovery this second Comet ASASSN was in the southern hemisphere's morning sky at a declination of -41 degrees, and was about 16th magnitude. It has remained in southern skies since that time, reaching a maximum southerly declination of -47 degrees around the time it went through opposition in late October. I took some images with the Las Cumbres Observatory telescope at Cerro Tololo in mid-July right around the time when the comet's discovery was announced, but didn't start making visual attempts until early October; my early attempts were all unsuccessful, and I'm sure the comet's location just a few degrees above my southern horizon didn't help matters. Finally, on my first attempt of the current dark run (by which time the comet had moved north to declination -42 degrees) on the evening of November 27 I successfully observed it as a faint, small, relatively "dense" object of 14th magnitude. Its appearance was similar when I observed it again the following night (although its proximity to a nearby 12th-magnitude star made the overall observation a bit difficult).

The fact that the comet is visually detectable at a heliocentric distance of 4.5 AU almost a full year before perihelion passage indicates that it is rather bright intrinsically and suggests I may be following it for quite some time, although its rather large perihelion distance will likely keep it from becoming bright. It is traveling in a steeply-inclined direct orbit (inclination 78 degrees) and at present is located in northeastern Phoenix about 1 1/2 degrees north-northwest of the star Gamma Phoenicis. For the time being it is traveling slowly towards the north-northwest, although gradually turning more and more directly northward; it crosses into Sculptor in mid-December and passes 40 arcminutes east of the Sculptor Dwarf Galaxy on January 2, 2019 before reaching its stationary point (when at a declination of -30 degrees) at the midpoint of that month. From that point it travels towards the north-northeast, crossing into Cetus in early February; from my latitude it disappears into evening twilight towards the end of that month but remains accessible from the southern hemisphere for perhaps another two to three weeks. By the time it disappears it may have brightened by about a half-magnitude or so.

The comet is in conjunction with the sun (18 degrees south of it) in mid-April, and emerges into the southern hemisphere's morning sky by early June and into the northern hemisphere's morning sky by about the beginning of July. It is still in Cetus at the time (although crossing into Aries by mid-July) and may be close to 12th magnitude. It continues traveling slowly towards the north-northeast, although gradually turning more and more westward -- passing through its stationary point in early August -- and then crosses into Triangulum in mid-September and into Andromeda a month later, at which time it will be near opposition and its closest approach to Earth (2.21 AU) and probably near a peak brightness of about 11th magnitude. The comet passes 2 1/2 degrees south of the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) in early November and for the next two months travels almost due westward at a declination of +39 degrees. It reaches its other stationary point in early January 2020 and thereafter turns back towards the northeast, crossing into Cassiopeia in early March. It is technically in conjunction with the sun again (50 degrees north of it) late that month, but at a declination near +52 degrees it should still be accessible for northern hemisphere observers. By then it will likely have faded to about 12th magnitude.

Following this "conjunction" with the sun, the comet continues traveling towards the northeast, entering northern circumpolar skies around mid-April and passing almost directly over the star Alpha Cassiopeiae (the second star from the western end of the "W") on April 12, 20 arcminutes northwest of the nearby sun-like star Eta Cassiopeiae five days later, and a similar distance southeast of the star Gamma Cassiopeiae (the middle star of the "W") ten days after that. It passes north of declination +80 degrees in late June and reaches a peak northerly declination of +85.4 degrees during the fourth week of July before passing back south of +80 degrees in mid-August; it is unlikely to be any brighter than 13th magnitude during this time. The comet remains in northern circumpolar skies for almost another year after that, but I suspect it will fade beyond the range of visual detectability by September or October.

If all goes well, then, I may be following this comet for well into the first year of the decade of the 2020s, a time that not too long ago almost seemed like something out of a science fiction story. But, it is nevertheless now almost a reality, and as I have hinted before in these pages and elsewhere on this web site, both my life personally and -- hopefully -- Earthrise may be in for some dramatic (and positive) changes by the time I am finished with this comet.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 November 28.17 UT, m1 = 13.8, 0.7' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (June 30, 2019): After being in conjunction with the sun in mid-April 2019, Comet ASASSN began emerging into the morning sky in May, but because it was south of the sun it was inaccessible from my latitude; I've lately been listing it under the "Southern Hemisphere Only" section of the "Currently Observable Comets" page. By the latter part of June it finally became accessible from my location, and after waiting for the moon to clear from the morning sky I successfully observed the comet on the last morning of the month; it appeared as a small, moderately condensed object slightly fainter than 13th magnitude. At present it is low in my eastern sky at the beginning of dawn, but it will climb higher over the coming weeks.

Comet ASASSN's present brightness suggests that the scenario described above may be a bit optimistic. I now expect a peak brightness around 12th magnitude when it is at opposition and perihelion later this year, and it should remain visually detectable for at least the first few months of 2020.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2019 June 30.43 UT, m1 = 13.4, 0.7' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

658. COMET IWAMOTO C/2018 Y1 Perihelion: 2019 February 7.03, q = 1.287 AU

Just six weeks after his independent discovery of Comet Machholz-Fujikawa-Iwamoto C/2018 V1 (no. 655), Japanese amateur astronomer Masayuki Iwamoto scored his third comet discovery on the morning of December 18, 2018, when he found it on a pair of CCD images he had taken. His countryman Ken-ichi Kadota successfully imaged it a day later, and shortly thereafter I noticed the potential comet listed on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page. On the following morning, December 20, I successfully located it as a rather diffuse 12th-magnitude object, and just a few hours later I was able to obtain images of it with one of the telescopes at the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Haleakala, Hawaii. To my rather excited delight both of these efforts are mentioned on the MPC's discovery announcement that came out later that day, with my colleague, British astronomer Richard Miles, having performed the astrometric measurements from the LCO images at my request.

After that, however, Comet Iwamoto rapidly accelerates northwestward through Virgo and then through Leo as it approaches Earth. According to the preliminary orbit, closest approach occurs on February 5 at a geocentric distance of 0.17 AU; at that time the comet would be traveling through the "head" of Leo at a rate of 13 degrees per day (i.e., over half a degree per hour) as it and Earth fly past each other in opposite directions. Based upon its present brightness, it could be a naked-eye object of about 6th magnitude around that time.

Following its passage by Earth, the comet continues traveling northwestward through Cancer, Gemini, and into Auriga, where it reaches a maximum northerly declination of +38 degrees around February 10. It then turns towards the east-southeast and slows down rapidly as it recedes from the earth and sun, and by early March it will be crawling along at well under 10 arcminutes per day (and continuing to slow down) near a point in southwestern Perseus a few degrees west of the star Zeta Persei. It will presumably fade fairly rapidly as well, and will likely drop below the range of visual detectability by sometime in April.

To reiterate, this scenario depends rather heavily upon the validity of the preliminary orbit. Although nothing has been officially published yet, I am reading indications that the "true" orbit, while being similar to the preliminary orbit in terms of its overall general characteristics, may have a later perihelion date (early February as opposed to late January) and a larger perihelion distance (1.25 to 1.3 AU as opposed to 1.14 AU). If this is true, the closest approach to Earth will be about a week later, and the minimum geocentric distance distinctly larger (around 0.3 AU); the corresponding peak brightness would accordingly be somewhat fainter, perhaps 7th to 8th magnitude. The "vanishing point," as it were, would be in southeastern Perseus a few degrees east of the star Xi Persei. In any event, hopefully within the not-too-distant future a more accurate orbital calculation will be available which will in turn allow us to better predict what to expect when the comet is closest to Earth in early February.

Regardless of how close Comet Iwamoto comes to Earth and how bright it gets, I will be experiencing my own special treat right around that same time. I have recently agreed to teach a course on "Small Bodies in the Solar System" -- a "mini-version" of the curriculum I have discussed elsewhere -- as part of the International Space University's Southern Hemisphere Space Studies Program that will be held in Adelaide, South Australia during late January and early February. It so happens that my older son Zachary and his girlfriend Karina are residing in Adelaide for the time being, and my girlfriend Vickie (who will be accompanying me) and I will be visiting them and touring the general area in and around the time I am teaching. Part of the program involves at least one public talk in conjunction with the Astronomical Society of South Australia, and I hope to use some of their observatory facilities to observe Comet Iwamoto as well as some of the other comets that will be around -- in addition, of course, to the spectacular sights in the sky that are only accessible from the southern hemisphere.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2018 December 20.51 UT, m1 = 11.5, 3.1' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (December 26, 2018): A just-published orbit -- which is probably reasonably close to "reality" -- suggests a scenario reasonably consistent with the alternate one described above: closest approach to Earth now takes place on February 12, 2019, at a geocentric distance of 0.30 AU. At that time Comet Iwamoto will be located a few degrees south of the "head" of the constellation Leo -- and near opposition -- and traveling towards the west-northwest at a little over seven degrees per day. As suggested above, it will presumably be in the vicinity of 7th to 8th magnitude then, although it will likely fade fairly rapidly thereafter.

Due to the full moon -- and to a series of winter storms currently passing through New Mexico -- I have not seen the comet since my initial observation. I hope to observe it again sometime shortly after the start of the New Year, and its brightness then will hopefully provide a better indication of what to expect when it is nearest Earth.

Zachary and Karina are heading back to Adelaide in a few days, although as I indicated above Vickie and I will be seeing them again -- in Adelaide -- in about a month's time. Tyler, meanwhile, will be remaining in the general area here as he continues work on his Electrical Engineering degree at New Mexico State University.

The comet has brightened fairly well, and appeared as a moderately condensed object of 10th magnitude when I last observed it a few mornings ago. Based upon its present brightness and the rate of brightening it has exhibited since its discovery, my expectation is that it might reach a peak brightness close to 7th magnitude when it is nearest Earth.

The image at right was taken on January 16, from the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2019 January 14.49 UT, m1 = 10.1, 4.5' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

659. COMET 123P/WEST-HARTLEY Perihelion: 2019 February 5.12, q = 2.127 AU

The new year of 2019 has now dawned on Planet Earth. The recently-ended year of 2018 was kind of a "mixed bag" for me; several people close to me and/or whom I've looked up to passed away, and I was forced to undergo a most frustrating experience involving back taxes. As I have discussed in previous entries, I also encountered the serious medical condition that required a week-long period of hospitalization in July, although I am happy to report that I have recovered quite nicely and am feeling as well now as I have in quite some time. On the positive side, although there is still quite a long way to go I have become fully engaged in developing Earthrise and overall I have positive feelings about its progression; as a part of this, as I discuss in the previous entry I will be departing soon for a teaching gig for the International Space University's Southern Hemisphere Space Studies Program in Adelaide, South Australia (and will be able to visit my older son Zachary and his girlfriend Karina in the process). Also on the positive side, my relationship with my girlfriend Vickie has grown from "steady dating" a year ago into a deep serious relationship, as I have finally been able to let go completely of my previous broken relationship, and I am happily looking forward to Vickie's moving in with me within the next couple of months.

Astronomically, 2019 may be somewhat of a quiet year, with one of the bigger events being the total lunar eclipse taking place later this month. (I have no plans to travel to South America for the total solar eclipse on July 2, although if the eclipsed sun were to have been higher in the sky I might have tried to travel to Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile -- which is directly in the path of totality -- and make another attempt to observe sungrazing comets during the eclipse.) I am presently following the asteroid (433) Eros which is making a somewhat-close approach to Earth at this time -- and reliving, to an extent, the Science Fair project I conducted on this object over four decades ago when I was in High School. Some of the comets that were bright in late 2018 are still around, including Comet 46P/Wirtanen (no. 653) which was still dimly visible to the naked eye at the very beginning of 2019 but which is now distinctly fading (although it remains visible with binoculars for the time being). The preceding comet on my tally may be somewhat bright when it is closest to Earth next month, but once these various comets fade out there really isn't much in the way of bright comets for quite some time -- unless, of course, one or more unexpected bright ones are discovered -- until the last couple of months of 2019, when Comet PANSTARRS C/2017 T2 should reach at least easy telescopic visibility, and be well-placed and fairly bright when I mark the 50th anniversary of my first comet observation a little over a year from now.

One interesting piece of astronomical research I am currently engaged in involves the main-belt asteroid (6478) Gault, which apparently underwent an impact by a smaller object late last year and which has recently exhibited a distinct dust tail. Via the Las Cumbres Observatory I was able to obtain one of the earliest confirming images of this feature, and was duly credited on the discovery announcement. As is the case with (596) Scheila and (493) Griseldis, Gault now becomes an "active asteroid" and is accordingly eligible for inclusion in my tally should I ever detect it visually; as it is, Gault will most likely remain too faint for me to see, although it is currently running about 1 1/2 magnitudes brighter than its ephemeris prediction, and if it should maintain this trend when it is at opposition at the end of February it conceivably could be amenable to visual detection then.

My first tally addition of 2019 is a rather dim and somewhat obscure short-period comet that I have observed once before. It first appeared on a photograph taken from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile in March 1989, however the comet's 17th-magnitude image was not noticed until almost two months later, when ESO astronomer Richard West spotted it. (West had discovered three comets in the mid- to late 1970s, one of these being the "Great" Comet West 1975n (no. 20), which even now I still consider as the best comet I have ever observed. I had the pleasure of meeting him at the First International Conference on Comet Hale-Bopp that was held in the Canary Islands in February 1998; we even had a playful good-natured "argument" over who had the better comet, each of us taking the position that the other's comet was "better.") The comet's motion was ambiguous from a single trailed exposure and early search attempts were unsuccessful, however near the end of May Malcolm Hartley -- whose name showed up a couple of times during "Countdown" -- at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales independently re-discovered the same comet. It was found to have passed perihelion the previous October and to be traveling in an orbit with a period of 7.6 years.

The comet returned in mid-1996 and I read a couple of reports that suggested that it might be bright enough for visual observations, however my one attempt (in mid-March) was unsuccessful. The following return, in late 2003, was more favorable geometrically, and I successfully picked it up (no. 346) near the end of that year when it was a couple of weeks past perihelion passage; I followed it for the next three months but it never got much brighter than 14th magnitude. The return in mid-2011 was rather unfavorable and I did not look for it.

On its present return Comet P/West-Hartley was recovered on August 3, 2017 by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii. After being in conjunction with the sun near the end of May 2018 it began emerging into the morning sky during the latter months of that year; I successfully imaged it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network in early December, but my two visual attempts that month were unsuccessful. My first attempt of the current dark run was on the morning of January 8, however unfortunately I had to contend with thin clouds; I did have a "suspect" but could never confirm this one way or the other, and I do not consider this as a valid observation. After a few more nights of cloudy weather I was finally able to make an attempt in clear skies shortly after midnight on the morning of January 12, and in the meantime I had read of a possible small outburst of the comet; I successfully detected it as a small and condensed object near magnitude 13 1/2.

The current return is quite favorable, with the comet's being at opposition shortly before mid-March and passing closest to Earth (1.20 AU) near the end of February. It is presently located in southern Ursa Major five degrees southeast of the star Xi Ursae Majoris, and is traveling slowly towards the northeast as it approaches its stationary point at the end of January, after which it begins retrograde (westward) motion. The comet spends the next several weeks in Ursa Major as it reaches a maximum northerly declination of +32 degrees at the beginning of March and passes 10 arcminutes north of the above star a week and a half later; it eventually crosses into eastern Leo Minor in late March and, now traveling in a generally southward direction, passes through its other stationary point in mid-April and crosses into northern Leo a week later. As far as its brightness is concerned, the recent possible small outburst complicates prediction efforts a bit, but I would think a peak brightness near 13th magnitude around the time of opposition is probably reasonable, with the comet's fading beyond visual range by sometime in April.

Since I will be spending three weeks in Australia -- where the comet will be quite low in the northern sky -- I probably will not be getting many observations of it for a while, although once I return I should be able to detect it easily enough during the latter part of the current apparition. After that, it is rather doubtful that I'll be seeing this comet again: the next return (perihelion late September 2026) is unfavorable and the one after that (perihelion late May 2034) is mediocre at best, and even if I am still active at some level it is quite unlikely that I'll be attempting any observations. The return in 2042 (perihelion late January) is a favorable one similar to this year's, but even under the best of scenarios I consider it rather improbable that I'll still be observing faint comets at the age of 83. But, we'll see . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 January 12.30 UT, m1 = 13.6, 0.5' coma, DC = 7 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

660. COMET P/BENNU P/1999 RQ36 Perihelion: 1999 November 19.40, q = 0.898 AU

I have discussed in several places elsewhere, including in the entries for "Comets" P/Scheila (no. 623), P/Phaethon (no. 633), and P/Griseldis (no. 651), as well as in the special note on my "Continuing With Comets" page, the rather nebulous dividing line between "comets" and "asteroids," and in a few cases where I have considered it appropriate -- generally, where the object in question has exhibited physical activity that could be considered "cometary" regardless of the mechanism that produced that activity -- I have retroactively added previously-observed "active asteroids" to my tally as "comets." I am now doing so again, for an object that I observed on a single occasion almost two decades ago.

The object in question was discovered on September 11, 1999 by the LINEAR program based in New Mexico (which had gone fully on-line early the previous year and which was dominating the discovery of comets and near-Earth asteroids at the time). The discovery announcement came out on the 14th, and indicated that it was quite bright (as far as newly-discovered near-Earth asteroids go) and was moving quite rapidly. On the morning of September 19 I successfully observed it and followed it for half an hour as it traveled against the background stars at a rate of 20 arcminutes per hour (8 degrees per day); it appeared completely stellar at magnitude 13 1/2. Because of the encroaching moonlight (full moon being on the 25th), the fact that the asteroid was moving interior of Earth and thus would soon fade rapidly due to the increasing phase angle, and also the fact that I left a couple of days later for Los Angeles to attend and speak at the annual conference of the Space Frontier Foundation -- where I mentioned the asteroid during my talk and, more importantly, met with some people who were able to provide some significant funding for my work -- I did not look for it again.

At the time of my observation of 1999 RQ36 it was located at a geocentric distance of 0.019 AU. It passed at a minimum geocentric distance of 0.015 AU on September 22, but all observations ceased within a couple of days later. After emerging from sunlight at the very end of 1999 it was observed as a faint object, with observations thereafter continuing for the next four months. It was recovered in 2005 en route to another close approach to Earth (0.033 AU) that September (during which, according to reports, it reached a peak brightness of 16th magnitude), and later that year it was assigned the permanent asteroid number (101955).

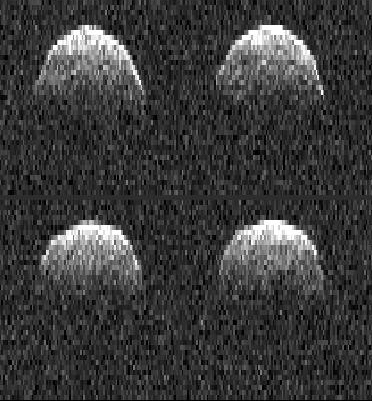

(101955) 1999 RQ36 has an orbital period of 437 days (1.20 years) and travels in a relatively low-eccentricity (0.20) low-inclination (6.0 degrees) orbit. Physical studies have indicated that it is roughly spherical in shape, and is about 500 meters (1700 feet) in diameter. It is relatively dark with a low geometric albedo and its internal structure appears to be relatively porous -- both characteristics of which are similar to those of comet nuclei -- and a recent study of its polarization also suggests a possible cometary origin. To date, however, no cometary activity has ever been detected from the ground or from near-Earth space.

In 2011 (101955) 1999 RQ36 was selected as the primary destination of NASA's then-upcoming Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission. Following a world-wide naming contest held by the OSIRIS-REx team, the LINEAR program, and The Planetary Society, in 2013 it was given the name "Bennu" after the heron-shaped Egyptian deity; the name was suggested by a 9-year-old student from North Carolina, Michael Puzio.

OSIRIS-REx was launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida on September 8, 2016, and following a gravity-assist flyby of Earth in September 2017 arrived at Bennu on December 3, 2018, entering orbit around it on December 31. Shortly after its arrival OSIRIS-REx detected the presence of water-related substances on Bennu's surface in the form of hydrated clays; while this is not necessarily a direct detection of water, it rather strongly suggests that some larger parent asteroid -- of which Bennu would be a fragment -- contained significant amounts of water.

On January 6, 2019, OSIRIS-REx's Navigation Camera detected a plume of dust grains and larger particles being ejected off Bennu's surface, and subsequently detected ten additional similar events through February 18. Analysis of these plumes indicate that they are made of particles a few centimeters in diameter and larger, and while some of these particles have apparently returned to Bennu's surface, others have been ejected completely away from Bennu, and in fact it is conceivable that some of these may eventually reach Earth in the form of a small meteor shower.

The OSIRIS-REx team announced the existence of these plume ejection events on March 19, 2019. At this time there is no firm explanation for the physical mechanism that produced these plumes, although sublimation of water and possibly other volatiles -- what could be considered regular cometary activity -- is certainly a possibility, and indeed appears to be among the more likely scenarios. (It is perhaps worth noting that Bennu passed through perihelion on January 10, 2019.) In any event, these events now mean that Bennu can be considered an "active asteroid," and following the precedent I have already established with other such objects, my observation of Bennu in 1999 now qualifies it for inclusion as a "comet" on my lifetime tally.

LEFT: A series of radar images (illustrating rotation) of (101955) Bennu -- then known as 1999 RQ36 -- obtained by NASA's Deep Space Network tracking antenna at Goldstone, California on September 23, 1999 (when Bennu was near its closest approach to Earth). Image courtesy NASA/JPL-CalTech. RIGHT: A composite of two images of Bennu taken by OSIRIS-REx's Navigation Camera on January 19, 2019, showing one of the plume ejection events. Image courtesy NASA/University of Arizona.

LEFT: A series of radar images (illustrating rotation) of (101955) Bennu -- then known as 1999 RQ36 -- obtained by NASA's Deep Space Network tracking antenna at Goldstone, California on September 23, 1999 (when Bennu was near its closest approach to Earth). Image courtesy NASA/JPL-CalTech. RIGHT: A composite of two images of Bennu taken by OSIRIS-REx's Navigation Camera on January 19, 2019, showing one of the plume ejection events. Image courtesy NASA/University of Arizona.

The OSIRIS-REx mission plan calls for the spacecraft to perform a "touch-and-go" touchdown and sample collection from Bennu's surface in mid-2020 (with the time between now and then being spent in reconnaissance and rehearsal of the sample retrieval process), although this may turn out to be a more difficult endeavor than originally anticipated since images have shown Bennu's surface to be covered with unexpectedly large boulders and a corresponding scarcity of suitable touchdown sites. OSIRIS-REx is then scheduled to leave Bennu in March 2021 en route to Earth, where it will arrive in September 2023 and deliver its collected soil samples. Once these have been analyzed we should have a better handle of, among other things, Bennu's water content and possible cometary origin.

Meanwhile, there is essentially no possibility that I will ever see Bennu again. It does not approach to even within 0.1 AU of Earth until February 2037 (when it approaches to just within that distance), and while it does pass 0.005 AU from Earth on September 23, 2060 (during which time it should reach 11th or 12th magnitude), I would be 102 years old then and I consider it rather unlikely that I'll be in any position to make observations. It makes an even closer approach to Earth on September 25, 2135, with a nominal (but uncertain) "miss distance" of 0.002 AU, and there is a minute possibility that it will impact Earth sometime during the late 22nd Century, although observations between now and then should certainly refine any predictions of such an event (and in fact will almost certainly eliminate that possibility).

It is not lost on me that, had it not been for the OSIRIS-REx mission, we would very likely have never known of the comet-like activity exhibited by Bennu, and I would not have been able to have added it to my tally; the observed activity level (thus far, anyway) is far too low to have been detected from Earth. (Incidentally, this retroactive addition to my tally gives me new personal records for the smallest geocentric distance at which I've observed a comet, and for the closest Earth-approaching comet I've observed.) This entire incident makes me wonder how many other similar objects might be out there; a recent study suggests that perhaps 8% or so of the near-Earth asteroid population might have a cometary origin, although it is perhaps worth noting that, of the various other asteroids that have been visited thus far by spacecraft, including the five that have been orbited (three of which are near-Earth objects), none have been seen to exhibit this type of activity. Over the years I have often observed near-Earth asteroids -- including newly-discovered ones such as 1999 RQ36 -- when they are bright enough for me to detect, and it is at least conceivable that one or more of these might be "active asteroids" aka "comets." One that comes to mind is the well-known asteroid (1566) Icarus, which appeared anomalously bright one night when I observed it during its close approach to Earth in June 2015; unfortunately it does not approach Earth again until June 2043. Another interesting such object is 2015 TB145, which both from photometric studies (which indicated a very low albedo) and its orbital parameters was suspected of being a possible "dead comet" at the time; I successfully observed it (in bright moonlight) as a 12th-magnitude object on Halloween morning of 2015 as it was passing just 0.003 AU (1.3 lunar distances) from Earth. Although it was recovered in late 2018 during its subsequent return to perihelion and its orbit is now very well known, it unfortunately does not make any close approaches to Earth again until one of 0.059 AU in November 2088, and thus it is quite unlikely that I will ever get a final verdict on its true physical nature during my lifetime.

OBSERVATION: 1999 September 19.41 UT, m1 = 13.5, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 183x)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center