TALLY ENTRIES 661-670

Over 3 1/2 months have elapsed since I made a "real-time" addition to my comet tally. (The previous entry, which I placed on the tally in late March, was a retroactive addition of an object that I observed almost 20 years ago.) This is the longest period of time that I have gone without a tally addition in over 12 years, and it has coincided with a general slowdown in cometary activity (in contrast to the high level of activity that was going on at the beginning of this year).

A lot has happened during these past 3 1/2 months. During the latter part of January Vickie and I traveled to Adelaide, South Australia for three weeks, where I taught a brief course on the "small bodies" of the solar system as a part of the International Space University's Southern Hemisphere Space Studies Program (and also was able to visit my older son Zachary and his girlfriend Karina, who have resided in Adelaide for the past three years while she has been pursuing doctoral studies at Flinders University). Vickie moved in with me at the end of February, making us full-fledged "domestic partners," and she has commenced turning my erstwhile "bachelor pad" into an actual respectable home. Meanwhile, over the fairly recent past I have been busy developing an expanded educational program around the solar system's "small bodies" which I hope to implement next year, and I plan to be making a statement about it (on this website) in a couple of months. Finally, in early March I "celebrated" birthday number 61, and for a birthday present Vickie treated me to a concert by Bob Seger that was held in Albuquerque; during that same trip we visited Santa Fe where I was able to meet with some educators and (together with Vickie) was formally introduced on the floor of the New Mexico State Senate.

The comet that ended the long drought of tally additions was discovered on February 26, 2019, by Heather Flewelling with the ATLAS program in Hawaii, utilizing the ATLAS telescope at Mauna Loa. Although it was too faint to attempt visually at the time, it was nevetheless relatively bright as far as recent survey discoveries go, and two weeks later I sucessfully obtained images of it with one of the Las Cumbres Observatory telescopes while it was still listed on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page. (Unfortunately, the star images were too trailed to allow valid astrometry to be performed.) After the comet's discovery was announced I attempted it visually a couple of times in early April, without success. After the April full moon I made another attempt on the morning of April 29 and suspected a very faint, diffuse, 14th-magnitude object, however the rising crescent moon and some possible thin clouds that moved in prevented me from confirming it. After one day of cloudy weather I was able to observe again, under good sky conditions, on the morning of May 1, and was able to verify my earlier suspect.

Comet Flewelling is traveling in a moderately-inclined orbit (inclination 34 degrees) with an approximate period of 1700 years. It is currently located in western Pegasus and is traveling towards the northeast at 50 arcminutes per day; it passes slightly to the northwest of the "Great Square" during the last week of May and enters western Andromeda during the second week of June, passing three degrees north of the Andromeda Galaxy M31 shortly after mid-July. By that time its motion will have slowed down to somewhat under 20 arcminutes per day and will be turning more directly eastward; it reaches its farthest north point (just south of declination +47 degrees) in mid-August, is at its stationary point a week and a half later, and is at opposition in early October. As far as the comet's brightness is concerned, with its being at perihelion in just a little over a week and being closest to Earth (1.57 AU) at the end of May it probably won't get much brighter than it already is, unless it undergoes some sort of post-perihelion brightening (which is not unprecedented for long-period comets that have made previous returns, as is the case with this one). In any event, though, I doubt if I will be following this comet much beyond the end of June.

Comet Flewelling C/2019 D1, as imaged by telescopes of the Las Cumbres Observatory. LEFT: March 13, 2019 -- at which time it was still listed on the Possible Comet Confirmation Page -- from the South African Astronomical Observatory. RIGHT: April 28, 2019 -- a little over 14 hours before I first picked it up visually -- from Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

Comet Flewelling C/2019 D1, as imaged by telescopes of the Las Cumbres Observatory. LEFT: March 13, 2019 -- at which time it was still listed on the Possible Comet Confirmation Page -- from the South African Astronomical Observatory. RIGHT: April 28, 2019 -- a little over 14 hours before I first picked it up visually -- from Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

Despite this latest addition to my tally, the comet activity will likely remain quite low for some time yet, and I don't expect this comet or either of the other two comets I am presently following -- one of which I am already about done with -- to be around for too much longer. It is always possible, of course, that some unexpected bright comets could appear in the not-too-distant future, but otherwise things will probably be pretty slow until I am able to pick up some of the expected comets later this year, including some of those listed on the "Notable Upcoming Comets" page.

CONFIRMING OBSERVATION: 2019 May 1.42 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.8' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

662. COMET LEMMON C/2018 R3 Perihelion: 2019 June 7.20, q = 1.291 AU

I've commented before in various previous entries about the random nature of appearances of comets in our skies; there are times when cometary activity can be quite high, as was the case during the last few months of last year, and there are times when the activity is very slow, as it is now. A symptom of the present low level of activity was the 3 1/2 months that elapsed before the previous entry to my tally; in general, that slow activity is continuing, but in somewhat of an unusual twist barely over a week elapsed between the addition of my previous entry and my addition of this one.

This particular comet was discovered on September 7, 2018, by Brian Africano during the course of the Mount Lemmon Survey based in Arizona. It was a faint object of about 19th magnitude that initially appeared asteroidal -- hence the name "Lemmon" -- but other observers soon began reporting it as being cometary. It remained faint for the next few months before disappearing into evening twilight, and after conjunction with the sun in late February it began emerging into the morning sky towards the end of March. I made an attempt for it in twilight in early April and didn't see anything, and CCD images that were taken shortly thereafter by other observers indicated that it was still quite faint, even more so than expected. While the viewing prospects were never very good, it now looked like the comet would remain too faint to become visually detectable.

It nevertheless did seem to brighten some over the next few weeks, according to CCD images that I saw. (Unfortunately, it remained too low to access with the Las Cumbres Observatory telescopes.) After the April full moon I made another attempt on the morning of the 29th -- the same morning I first observed the previous comet -- and didn't see anything, but when I tried for it again on the morning of May 8 I was rather surprised to see a faint, diffuse, 13th-magnitude patch of light that moved noticeably against the background stars over a period of 15 to 20 minutes. While there were no real doubts in my mind that I had indeed observed the comet, I was nevertheless delighted to see a CCD image that was posted later that same day by Austrian amateur astronomer Michael Jaeger; he had taken the image a few hours before my visual observation, and it clearly showed the comet as being bright enough to be within my visual range.

The viewing geometry remains poor throughout Comet Lemmon's apparition. It is presently low in the northeastern sky at dawn, being located in western Perseus some six degrees east of the star Theta Cassiopeiae, and is actually at its maximum elongation from the sun, just under 41 degrees. It is traveling towards the east-northeast at slightly over one degree per day, passing through the northern regions of the two members of the "Double Cluster" (NGC 869 and NGC 884) on May 14 and crossing into southeastern Cassiopeia two days later before entering Camelopardalis five days after that (while passing half a degree south of the open star cluster Stock 23 in the process). The comet is closest to Earth (1.92 AU) on May 23, is at its maximum northerly declination (+60 degrees) four days later, and is in conjunction with the sun (38 degrees north of it) just before the end of May. While technically it is an evening-sky object at the time of perihelion passage on June 7, it is buried in twilight at a fairly small elongation, and the elongation keeps shrinking for the next several weeks as the comet recedes from perihelion on the far side of the sun from Earth. It finally becomes accessible in the morning sky during the last two to three months of 2019 but it will likely be very faint by then.

Even though the comet's recent brightening trend suggests it might brighten still further as it approaches perihelion, its poor placement in the sky will keep it from being easily observed. Theoretically, I have about one week to view it before the full moon washes out the morning sky, however since my initial sighting on the 8th the first of a series of rain storms has arrived in southern New Mexico, and the current forecast indicates that the rain may continue throughout the rest of that week. It is thus entirely possible that my sighting of the comet on the 8th will remain my only observation of it; should that be the case Comet Lemmon would become my 33rd "one-time wonder," a group that constitutes almost exactly 5% of all the comets on my tally.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 May 8.44 UT, m1 = 13.3, 1.3' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (May 12, 2019): Comet Lemmon turns out not to be a "one-time wonder" after all! We've had a brief break in the series of rain storms that are currently traveling across southern New Mexico, and although I had to play a little "dodge-the-clouds" this morning I was able to view the comet again. While my observation was necessarily rather brief, it was enough to see that the comet is slightly brighter and larger than it was four days ago.

It is reasonable to expect that Comet Lemmon might continue brightening as it approaches perihelion early next month, however the decreasing elongation, as well as the full moon which will be arriving in a few days, will likely prevent it from becoming a prominent object. I am quite probably finished with it.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2019 May 12.44 UT, m1 = 13.0, 1.6' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (May 28, 2019): Comet Lemmon continues to brighten as it approaches perihelion. It is presently near conjunction with the sun -- some 39 degrees north of it -- and recent reports from observers at northern latitudes have indicated a current brightness near magnitude 11 1/2. Although it is not an easy object to access from my latitude, I was nevertheless able to verify these reports for myself last night when I was able to grab an observation of it low above my northwestern horizon, in twilight.

Over the next couple of weeks the comet will gradually climb higher into the northwestern evening sky, and with perihelion passage still a week and a half away it may still brighten a bit further. At the same time, its elongation steadily decreases -- to below 35 degrees by mid-June, and to below 30 degrees a week and a half later -- as it recedes from perihelion on the far side of the sun from Earth, and it will likely not remain visible for much longer. I am hopeful of possibly getting another one or two observations of it before it's gone.

At this time Comet Lemmon is in southern Camelopardalis, five degrees west of the star Beta Camelopardalis and near its maximum northerly declination of +60 degrees. It is traveling just southward of due east at a little over 65 arcminutes per day, and passes one degree south of that star (and 20 arcminutes north of the star pair 11 and 12 Camelopardalis) on June 2.

Curiously, the southern hemisphere has its own version of Comet Lemmon at the moment. Comet Catalina C/2018 W1 was discovered on November 16, 2018 by Greg Leonard during the course of the Catalina Sky Survey based in Arizona; it was initially reported as being asteroidal in appearance but began to exhibit weak cometary activity three weeks later. It remained faint -- never brighter than 17th magnitude -- up until the time it disappeared into evening twilight in early March 2019, however recent reports from observers in the southern hemisphere indicate a present brightness between 11th and 12th magnitude. The comet is traveling in a steeply-inclined orbit (inclination 83 degrees) and passed through perihelion on May 11, 2019 -- only 11 minutes after the perihelion passage of Comet Flewelling C/2019 D1 (no. 661), although there is no relation between the two objects -- at a heliocentric distance of 1.360 AU; it is a Halley-type comet, with an orbital period of 102 years. It is currently located in northwestern Columba at an elongation of 50 degrees (almost due south of the sun) and is traveling towards the east-southeast at close to one degree per day; it passes 50 arcminutes northeast of Comet PANSTARRS C/2016 M1 (no. 629) on June 8.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2019 May 28.14 UT, m1 = 11.5 (extinction corrected), 2.0' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x; low altitude, twilight)

663. COMET AFRICANO C/2018 W2 Perihelion: 2019 September 5.73, q = 1.455 AU

In this present-day era of the comprehensive sky surveys, it would not seem to be surprising that, on occasion, a comet would be independently discovered by two or more different surveys, and indeed that has happened from time to time. Such was the case with this particular comet, which was independently discovered on November 27, 2018 by Hannes Groeller with the Catalina Sky Survey based in Arizona, and by Brian Africano with the Mount Lemmon Survey, also based in Arizona. (Even though the Catalina and Mount Lemon Surveys are under the same management and utilize the same personnel, their respective survey routines are nevertheless independent of each other.) Although Groeller's discovery preceded Africano's by about half an hour, Africano's report arrived at the Minor Planet Center 20 minutes before Groeller's report did, and in fact the discovery had already been posted on the Near-Earth Object Confirmation Page before the later report arrived, hence the comet was assigned Africano's name.

At the time of its discovery Comet Africano was a relatively dim object of 18th magnitude, located in the morning sky in northern Canes Venatici at a declination of +44 degrees. It is traveling in a steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 117 degrees) and moved steadily northward after discovery, entering northern circumpolar skies in early January 2019 where it has remained ever since, and passing within 70 arcminutes of the North Celestial Pole shortly before mid-March. I made a couple of unsuccessful attempts for it in late April and early May when it was low in my northwestern sky after dusk, and after it went through conjunction with the sun (47 degrees north of it) during the latter part of May it has now become accessible low in the northeastern sky before dawn. I first successfully observed it on the morning of June 8 as a small and moderately condensed object of 14th magnitude.

Although traveling southward, the comet remains in northern circumpolar skies for another two months. It is currently located in southwestern Camelopardalis at a declination of +63 degrees, slightly to the east of the open star cluster NGC 1502 and the chain of stars known as "Kemble's Cascade" and, being on the opposite side of the sun from Earth, is traveling very slowly towards the south-southeast. As it and Earth travel towards each other and eventually fly past each other, its motion begins to accelerate as it turns more directly southward and then towards the south-southwest. It crosses into Perseus at the end of August and over the course of the subsequent month plunges through that constellation, Andromeda, eastern Pegasus, and western Pisces; it is at opposition in mid-September and on September 27 it passes 0.49 AU from Earth, at which time it will be traveling at slightly over 3 1/2 degrees per day. Based upon its present brightness the comet should be somewhere between 9th and 10th magnitude at that time, and thus possibly detectable with ordinary binoculars.

Following its passage by Earth, Comet Africano continues its general southward plunge although it starts to slow down, crossing into eastern Aquarius in early October (and passing 20 arcminutes southeast of the Helix Nebula (NGC 7293) on the 11th) and then Piscis Austrinus and finally into Grus by month's end. It reaches a stationary point in mid-November, by which time its declination will be -42 degrees and its motion will have dropped to just over 10 arcminutes per day; it will likely have faded to about 12th magnitude by then. The rest of the comet's apparition is rather anti-climactic as it continues traveling slowly towards the south-southeast, and by the end of 2019 it will be at a declination of -46 degrees before passing just less than half a degree north of the star Alpha Gruis (Alnair) at the end of the first week of January 2020. By that time it will no longer be accessible from my latitude and in any event will likely have faded beyond the range of visual detectability.

The overall comet activity has been rather quiet for the past few months, and although it probably won't become especially bright, Comet Africano's appearance should nevertheless liven things up at least a little bit, together with a few other inbound comets that I may be picking up within the not-too-distant future. Meanwhile, I've got a couple of interesting efforts in the works -- including the "small bodies" educational program that I've mentioned in previous entries -- and hope to make some public announcements about these shortly.

And on the personal side . . . I've recently learned that I've become a grandfather, of sorts: my younger son Tyler has recently begun dating a young lady (Sara) who has a six-year-old daughter (Avery) from a previous relationship. Given the circumstances, I suppose that "grandfather" might be a bit of a stretch, but this is a phase of life that I was expecting sooner or later, and in any event I wish the new couple all the best.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 June 8.43 UT, m1 = 14.0, 0.8' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

664. COMET LINEAR C/2017 B3 Perihelion: 2019 February 2.50, q = 3.921 AU

Exactly fifty years ago this month, i.e., in July 1969, the Apollo 11 mission successfully completed humanity's first manned landing on the moon and safe return to Earth. As a child growing up in the 1960s I was totally caught up in the entire "rush to the moon!" effort, and I vividly remember, at the age of 11, watching the Apollo 11 moonwalk on July 20 with my family on the black-and-white TV we had in our living room. I still have the photographs I took from the TV screen during the moonwalk.

At the time I honestly believed I was seeing a preview of my own future. That obviously did not happen, of course, one major reason being that, once the political goals had been accomplished, American society by and large lost interest in the effort. (Not me, certainly; I continued avidly following the remaining Apollo missions.) The career and other personal decisions I made at a young age -- including what in hindsight are obvious mistakes -- played a non-trivial role as well. Still, I have had what by many accounts could be considered a reasonably decent career and have made my own contributions to the exploration of space, including my involvement in the radio science experiment of Voyager 2's encounter with Uranus in 1986. My doctoral dissertation continues to be cited on a fairly regular basis, and the comet and asteroid observations I have made over the years -- including some mentioned in these pages -- have also contributed to the cause, including assisting in some spacecraft missions. And, certainly, there was that comet discovery I managed to make . . .

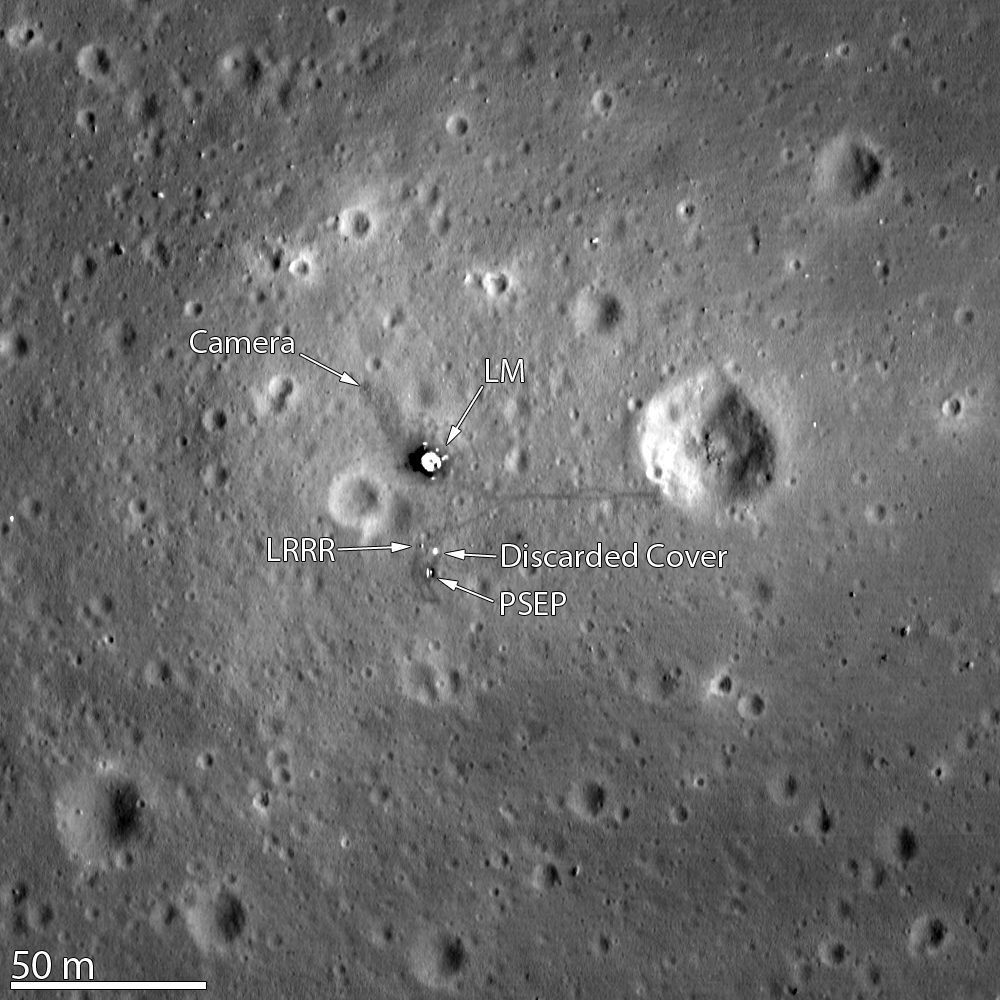

LEFT: Neil Armstrong's first step onto the lunar surface, July 20, 1969. I took this photograph directly from the TV broadcast of the moonwalk. RIGHT: The Apollo 11 landing site on the Sea of Tranquility, as imaged from 15 miles (24 km) above the lunar surface by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter on November 5, 2011. Image courtesy NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Arizona State University.

LEFT: Neil Armstrong's first step onto the lunar surface, July 20, 1969. I took this photograph directly from the TV broadcast of the moonwalk. RIGHT: The Apollo 11 landing site on the Sea of Tranquility, as imaged from 15 miles (24 km) above the lunar surface by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter on November 5, 2011. Image courtesy NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/Arizona State University.

And now, 50 years after Apollo 11 . . . I am able to mark the occasion by making another addition to my comet tally, although in keeping with the overall current low level of comet activity this is another faint one. The discovery comes courtesy of the LINEAR program in New Mexico, which dominated comet and asteroid discoveries during the first few years of the 21st Century and which I mentioned several times in "Countdown" entries. The LINEAR program as it then existed closed down near the end of 2012, with its final comet discovery being C/2012 X1 (no. 533); as I comment in that object's entry, LINEAR had by that time 214 named comet discoveries to its credit. During the middle years of this decade, meanwhile, LINEAR tested a 3.5-meter "Space Surveillance Telescope" (SST) from an adjacent site on White Sands Missile Range and discovered six additional comets, two of which I've seen (C/2016 A8 (no. 602) and this one); together with two previously-discovered "asteroids" found by LINEAR that exhibited cometary activity on subsequent returns, LINEAR's comet discovery total now stands at 222. I've managed to observe 69 of these comets, and after including multiple returns of short-period comets the name "LINEAR" now appears 72 times in my tally, which is not only far and away first place among comet names on my tally, but constitutes almost 11% of all the comets on it. The SST, meanwhile, is scheduled to be deployed near Exmouth, Western Australia, within the not-too-distant future, and presumably we might be seeing more LINEAR-discovered comets before much longer.

This particular comet is LINEAR's final comet discovery (as of now, anyway). LINEAR discovered it as long ago as January 26, 2017, at which time it was a dim 18th-magnitude object located 7.15 AU from the sun and slightly over two years away from perihelion passage. Traveling in a moderately-inclined direct orbit (inclination 54 degrees), Comet LINEAR gradually traveled southward from its discovery location (declination -24 degrees) and entered southern circumpolar skies in early 2018, where it remained for the next twelve months and reached a peak southerly declination of -68.7 degrees in mid-November. I am not aware of any visual observations that might have been attempted throughout this time, but CCD reports I have seen suggest a brightness near 15th magnitude during the latter months of 2018.

I had hopes of attempting Comet LINEAR when I was in South Australia during January/February of this year, but it was near conjunction with the sun (43 degrees south of it) at the time; furthermore, this was in a bad direction -- directly into the skyglow of Adelaide -- from Stockport Observatory (where I had a couple of observing sessions), and thus I was never able to make such an attempt. As the comet gradually traveled northward and began emerging into the southern hemisphere's morning sky I was somewhat surprised not to read of any observation reports, so in early May I took some images with the Las Cumbres Observatory, and saw that it was in fact quite prominent and well-developed. After I posted this in relevant forums, I did start to see some scattered visual observation reports from observers in the southern hemisphere that indicated the comet was around 14th magnitude.

Reports since then have nevertheless continued to be few and far between. Meanwhile, by mid-July the comet had finally become accessible from my latitude, very low in my southeastern sky just before the beginning of dawn, and I made my first attempt for it on the morning of July 11 but couldn't see anything that was convincing. I took another Las Cumbres image shortly thereafter, which showed that the comet remained prominent and well-developed, and suggested that I hadn't missed it by much. After clouds and rain the following morning, on the morning after that -- the 13th -- with good sky conditions and armed with the knowledge of exactly where to look and what to look for, I successfully detected the comet as a very faint, small, moderately condensed object of 14th magnitude. With its being located only two to three degress above the range of hills to my south it was very close to the limit of visibility.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet LINEAR C/2017 B3. LEFT: May 5, 2019, from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. RIGHT: July 11, 2019, from Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet LINEAR C/2017 B3. LEFT: May 5, 2019, from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. RIGHT: July 11, 2019, from Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

Comet LINEAR is currently located in northern Phoenix 1 1/2 degrees south-southeast of the star Kappa Phoenicis at a declination of -45 degrees and, having passed through its stationary point at the beginning of July, is now traveling slowly towards the west-southwest; it passes 20 arcminutes south of the star Epsilon Phoenicis on August 12 and reaches a maximum southerly declination of -46.1 degrees three days later before gradually turning towards the northwest, crossing into eastern Grus in mid-September and crossing north of declination -40 degrees one month later. Meanwhile, the comet is nearest Earth (3.48 AU) on August 20 and is at opposition in mid-September.

I don't expect much change in the comet's brightness over the next few weeks, and although it will remain quite low above my southern horizon it should climb marginally higher as it approaches opposition, and thus I expect to be able to observe it for at least that long. After that, however, it will likely be fading as it recedes from both the earth and the sun, and I doubt if I'll be able to follow it for much longer.

In addition to all the Apollo 11 retrospectives going on right now, events are happening, both here at home and in the wider world. For the past few months I have been putting together an educational program, "Ice and Stone 2020," which I formally announced at the beginning of July and about which I'll have more to say in a subsequent entry. One of the "wider world" events that I have found interesting is the series of earthquakes that struck Ridgecrest, California earlier this month, including the 7.1 quake on July 5. Ridgecrest is next to the China Lake Naval Air Weapons Station, and during the latter part of my Navy years in the early 1980s I made regular visits to China Lake as a part of my job. I would usually take my telescope -- the Meade 8-inch (20 cm) Newtonian reflector that I still have and use on occasion -- with me, and observe from a desert site south of Ridgecrest. A few of the comet observations on my lifetime list were made from this site during the course of these trips.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 July 13.43 UT, m1 = 13.8 (extinction corrected), 0.5' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

665. COMET 68P/KLEMOLA Perihelion: 2019 November 9.04, q = 1.794 AU

The low level of cometary activity that has persisted throughout much of 2019 continues . . . But there are signs that, at long last, the activity level may soon start to increase, at least a little bit. One of these signs is that, during a span of two nights just before the end of July I was able to add three comets to my lifetime tally. Perhaps more importantly, one of these comets has the potential to become moderately bright over the next several months.

Not this one, however. This is a rather unremarkable periodic comet that was originally discovered in late October 1965 by an American astronomer, Arnold Klemola, who at the time was working at the Yale-Columbia Southern Station in Argentina. (Klemola, who just passed away early this year, discovered a total of 16 asteroids while there, but this was his only comet discovery.) The comet was a dim object of 17th magnitude at the time of its discovery -- which took place when a much, much brighter comet, the Kreutz sungrazer Comet Ikeya-Seki 1965f, was in the sky and occupying astronomers' attention -- and was only followed for a month and a half, but the observations were sufficient to show that it had passed perihelion back in mid-August and that it had an orbital period of 11 years.

Comet Klemola subsequently returned in August 1976, and was an unexpectedly bright 12th magnitude -- and thus bright enough for visual observations -- when it was recovered a few days prior to its perihelion passage. Unfortunately for me, this was right in the middle of my "Plebe Summer" basic training at the U.S. Naval Academy and I was not in any kind of position where I could make comet observations, and thus all I could do was read the observation reports from other observers, and bide my time for a future return.

I would finally get my opportunity to view Comet Klemola at the subsequent return in 1987. By late May of that year I had survived my first year of graduate school at New Mexico State University and my first four months of parenthood -- my older son Zachary having been born in mid-January -- and had just traveled to the Riverside Telescope Makers' Conference in California. While there I spotted a used Meade DS-16 16-inch (41 cm) reflector that was being sold for a very low price, and purchased it on the spot and brought it back home to Las Cruces. While Comet Klemola was not the first comet I observed with that telescope, it was the first comet I added to my tally (no. 101) with it, just a few days after returning home. That telescope, of course, has since become my prime observing instrument, and would be the Hale-Bopp discovery telescope eight years later; I still use it all the time for my observing efforts.

I followed Comet Klemola for 4 1/2 months in 1987 as it reached a peak brightness of magnitude 12 1/2. The next two returns, in 1998 and 2009, were unfavorable and I did not look for it. On the present return it was recovered on February 2, 2019 by Japanese amateur astronomer Toshihiko Ikemura.

Although the viewing geometry during this year's return is the best since 1987, it still did not strike me as being especially favorable, and I had no real plans to look for the comet. However, some of the recent astrometric brightness measurements I've read, and some of the CCD images I've seen, suggested that it might in fact be worth attempting, and I made a few unsuccessful attempts in late June and early July. After the full moon I made a couple of more attempts later in July, although the sky conditions were not especially good -- this is monsoon season here, even though the activity thus far this year has been weaker than average -- and the comet was in poor star fields on the occasions in question; at times I thought I might perhaps be seeing "something" but there was nothing that I found convincing. Finally, on the evening of July 29 I had good sky conditions and the comet was in a good field, and I successfully located it as a very faint, small, moderately condensed object of 14th magnitude.

Although the comet is still three months away from perihelion passage, it was already at opposition in mid-June and was closest to Earth (1.25 AU) a month later. It might remain visible for at least a while and might become marginally brighter over the next couple of months, but in all honesty -- despite the fact that, at present, it is my only evening-sky comet -- I doubt if I will be devoting much attention to it, although I will likely check in on it from time to time. It is currently located in central Ophiuchus about four degrees east-southeast of the globular star cluster M10 and, having just passed through its stationary point, will now be traveling towards the east-southeast, crossing into Serpens Cauda in early September, into Scutum at the beginning of October, and into northern Sagittarius shortly after the middle of that month. On September 30 it crosses the northern regions of the open star cluster M16 and the associated "Eagle Nebula."

This will almost certainly be the last return at which I ever observe Comet Klemola. Over and above any potential "retirement" along the lines that I have alluded to from time to time in these pages, an approach to Jupiter (0.21 AU) in 2028 will increase the perihelion distance to 1.92 AU and the orbital period to 12 years. Even though the viewing geometry at the next return in 2030 will be very similar to this year's, the increased distances would likely render the comet too faint for me to observe visually. Approaches to both Jupiter and Saturn during its subsequent orbit will increase the perihelion distance still further to a little over 2 AU and the orbital period to almost 13 years.

At the very least, though, while Comet Klemola may have been the first comet I ever added to my tally with the 41-cm telescope, it hasn't been my last . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 July 30.13 UT, m1 = 14.1, 0.8' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

666. COMET 260P/McNAUGHT Perihelion: 2019 September 9.96, q = 1.417 AU

"The Devil's comet" . . . In some forms of Christian theology, the number "666" refers to "the Number of The Beast" and the "end times," and while I don't subscribe to any such beliefs, as the tally number "666" has approached over the past several months I couldn't help but be curious as to what comet would end up with that distinction. As it turns out, the discoverer of my 666th comet, Rob McNaught, is a personal friend, and a warm and friendly human being; he is also an excellent astronomer, and has made many invaluable contributions to our astronomical knowledge over the past few decades, including -- among other things -- his many comet discoveries. Quite a few of his discoveries came as a result of his participation in the Siding Spring Survey that was conducted from New South Wales from 2004 to 2013, and several of the comets I observed during "Countdown" carry his name.

Rob discovered this particular comet in May 2005, and it was found to have an orbital period of 7.1 years. I managed to obtain a handful of observations of it (no. 379) as a faint object around the time of its perihelion passage, and then observed it again during the somewhat more favorable return in 2012 (no. 509); I discuss my observations of it in its tally entry. During its present return it was recovered on April 2, 2019 by Martin Masek at the private Pierre Auger Observatory in Malargue, Czech Republic; curiously, he had also recovered this same comet in 2012. The geometry this year is almost identical to that in 2012 -- the respective perihelion times being less than three days apart -- however a moderately close approach to Jupiter (1.08 AU) in May 2017 has decreased the perihelion distance from 1.50 AU to the present value (and also shortened the orbital period to 6.9 years), and thus the viewing circumstances this year are a bit better than they were in 2012.

For at least the near term Comet McNaught remains primarily a morning-sky object. It is currently located in eastern Pisces and is heading towards the northeast, crossing into Aries in mid-August and into Perseus during the latter part of September. It reaches its stationary point -- about three degrees east of the star Algol -- at the end of the first week of October, and then turns westward, crossing into northeastern Andromeda near the end of October -- at which time it is at opposition -- and reaching a maximum northerly declination of +50.2 degrees two weeks later.

The comet is closest to Earth (0.56 AU) in early October. Based upon its behavior in 2012 and making some allowances for the smaller distances this year, I expect a peak brightness of perhaps 12th magnitude between early September and early October, with fading therafter; by the time it reaches its farthest north point I suspect it will be close to fading beyond visual range.

I thus should get at least a reasonably decent run of observations of Comet McNaught this time around. This may be the last time I see it; any future returns are after the "retirement" timeframe that I have discussed elsewhere, although as I write these words I may or may not stick to that -- I'll cross that proverbial bridge when I get there. If I do keep on going, the comet's next return, in 2026 (perihelion early August), is quite similar to the one in 2005, and with the smaller distances involved visual observations should be possible. But that would definitely be my final return; another distant approach to Jupiter (1.82 AU) in 2028 increases the perihelion distance to 1.45 AU and the orbital period to almost exactly 7.0 years, which will cause the next several successive returns to be under relatively unfavorable viewing geometry.

As I indicated at the beginning of the previous entry, Comet McNaught was the second comet of a trio that I added during a span of two nights. Just before dawn broke I added another comet to my tally on the morning of July 31, the 34th time that I have added two or more comets to my tally during a single night.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 July 31.38 UT, m1 = 13.6, 0.8' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

667. COMET PANSTARRS C/2017 T2 Perihelion: 2020 May 4.95, q = 1.615 AU

I have been eagerly awaiting this comet, indeed, I daresay that the entire community of comet astronomers has been awaiting it. The Pan-STARRS program in Hawaii discovered it as long ago as October 2, 2017, at which time it was over 2 1/2 years away from perihelion passage and located at a heliocentric distance of 9.25 AU; the overall brightness then was about 19th magnitude. The comet is clearly fairly bright intrinsically and thus has the potential to be somewhat bright around the time of perihelion passage, although the somewhat large perihelion distance will likely keep it from becoming especially bright or prominent.

The comet was at opposition shortly before mid-November 2017, and brightened slowly over the next few months before disappearing into evening twilight in early 2018 en route to conjunction with the sun in mid-May. After emerging into the morning sky a couple of months later it was again at opposition in mid-November, and some of the reports I read and CCD images I saw -- including a set of Las Cumbres Observatory images I took in early October -- suggested it was running a bit brighter than expected and might even be worth visual observation attempts, but my attempts then were unsuccessful. I continued to take occasional LCO images of it and make occasional visual attempts up until the time it disappeared into evening twilight around the end of March 2019, and while these visual attempts continued to be unsuccessful, the LCO images did seem to indicate that it was brightening.

After being in conjunction with the sun in mid-May Comet PANSTARRS began emerging into the southern hemisphere's morning sky around the end of June, and an early CCD report suggested it might be somewhere in the vicinity of magnitude 13.5, and an LCO image I took a few days later was not inconsistent with this. I also made a visual attempt around that same time -- right after the comet had crossed the northern regions of the Hyades star cluster and was quite close to the star Aldebaran -- but dawn was already underway before I could get to the field and I did not see anything convincing. After waiting for the subsequent full moon to clear from the morning sky I tried again on the morning of July 31 (an hour and a half after adding the previous comet to my tally); initially the field was quite low and I didn't see anything convincing at first, but as the field rose higher, shortly before the beginning of dawn I clearly detected the comet as a small, condensed object of 14th magnitude.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet PANSTARRS C/2017 T2. Left: October 9, 2018, from the South African Astronomical Observatory. Right: August 2, 2019 (just over two days after I first picked up the comet visually) from Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet PANSTARRS C/2017 T2. Left: October 9, 2018, from the South African Astronomical Observatory. Right: August 2, 2019 (just over two days after I first picked up the comet visually) from Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

At this time Comet PANSTARRS is located in eastern Taurus above five degrees east-northeast of Aldebaran. It is traveling in a moderately-inclined direct orbit (inclination 57 degrees) and for the time being is traveling towards the east-northeast; it gradually curves more northward, crossing into Auriga (2 1/2 degrees east of the star Beta Tauri) in early October and passing through its stationary point a week and a half later. It then turns towards the north-northwest, passing 20 arcminutes east of the open star cluster M36 on October 28, one degree east of the open star cluster M38 six days later, and three degrees west of the star Capella at the end of November before crossing into eastern Perseus a few days later, at which time it is at opposition. Continuing its northwestward climb, the comet passes 15 arcminutes northeast of the open star cluster NGC 1528 on December 15 and is nearest Earth (1.52 AU) just before the end of December. It passes just over half a degree north of the "Double Cluster" in late January 2020, crosses into eastern Cassiopeia in mid-February, and passes through its other stationary point a week later when it will be located five degrees east-southeast of the star Delta Cassiopeiae.

Afterwards the comet travels towards the north-northeast as it enters northern circumpolar skies, passing three degrees east of the star Epsilon Cassiopeiae (the easternmost star of the "W") in mid-March and crossing into Camelopardalis during the second week of April. It reaches its farthest north point -- declination +76.3 degrees -- at the time of perihelion passage and then begins traveling towards the south-southwest, crossing into western Ursa Major during the third week of May, passing one degree northeast of the bright galaxies M81 and M82 on May 23, and crossing diagonally across the "bowl" of the Big Dipper during the first half of June. Later that month it crosses into Canes Venatici (passing one degree southwest of the bright galaxy M106 on the 24th) and in mid-July it crosses into Coma Berenices and shortly thereafter spends a couple of days traversing the northeastern regions of the Coma Galaxy Cluster (Abell 1656). The comet crosses into southwestern Bootes during the first week of August and then into Virgo late that month before entering Libra in late September; by that time it is getting low in the west after dusk and will soon be lost in twilight. After being in conjunction with the sun -- and passing almost directly behind the sun -- in late November it begins to emerge into the morning sky by mid-January 2021, initially in southern Ophiuchus and traveling southward, crossing into Scorpius shortly before the end of that month.

As far as brightness predictions go, as is always the case with incoming long-period comets those can be problematical. At this time Comet PANSTARRS seems to be quite "solid," however orbital calculations suggest it is a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, and such objects tend to under-perform more often than not. Nevertheless, its high intrinsic brightness suggests that it should reach a peak brightness of at least 8th or 9th magnitude, and moreover should remain this bright throughout the first several months of 2020. It is conceivable that the comet could reach faint naked-eye brightness -- perhaps 6th magnitude -- around the time of perihelion. Afterwards, it should remain visually detectable up through the time it disappears into twilight around October, and perhaps may still be detectable as a faint object for a few weeks after it emerges into the morning sky in early 2021.

Provided, then, that Comet PANSTARRS behaves at least somewhat "normally," we should have a decent comet to observe throughout a good part of next year (at least, for those of us in the northern hemisphere; southern hemisphere observers are mostly left out, although considering that they had the last two "Great Comets" almost entirely to themselves, perhaps that's fair.) The timing here is quite good . . . For the past several weeks I have been developing an educational program, which I've decided to call "Ice and Stone 2020," around the "small bodies" of the solar system (i.e., asteroids, comets, and the like). I'm keying on the fact that 2020 marks both the 25th anniversary of my discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp and the 50th anniversary of my very first comet observation. (Curiously, on the specific anniversary date -- the evening of February 2 -- Comet PANSTARRS will be located almost exactly 35 degrees due north of where Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka 1969g was located on that fateful night half a century ago.) I intend to include observations of Comet PANSTARRS as an element of the overall program, although, obviously, if any other bright comet(s) should happen to come along I would include it/them as well.

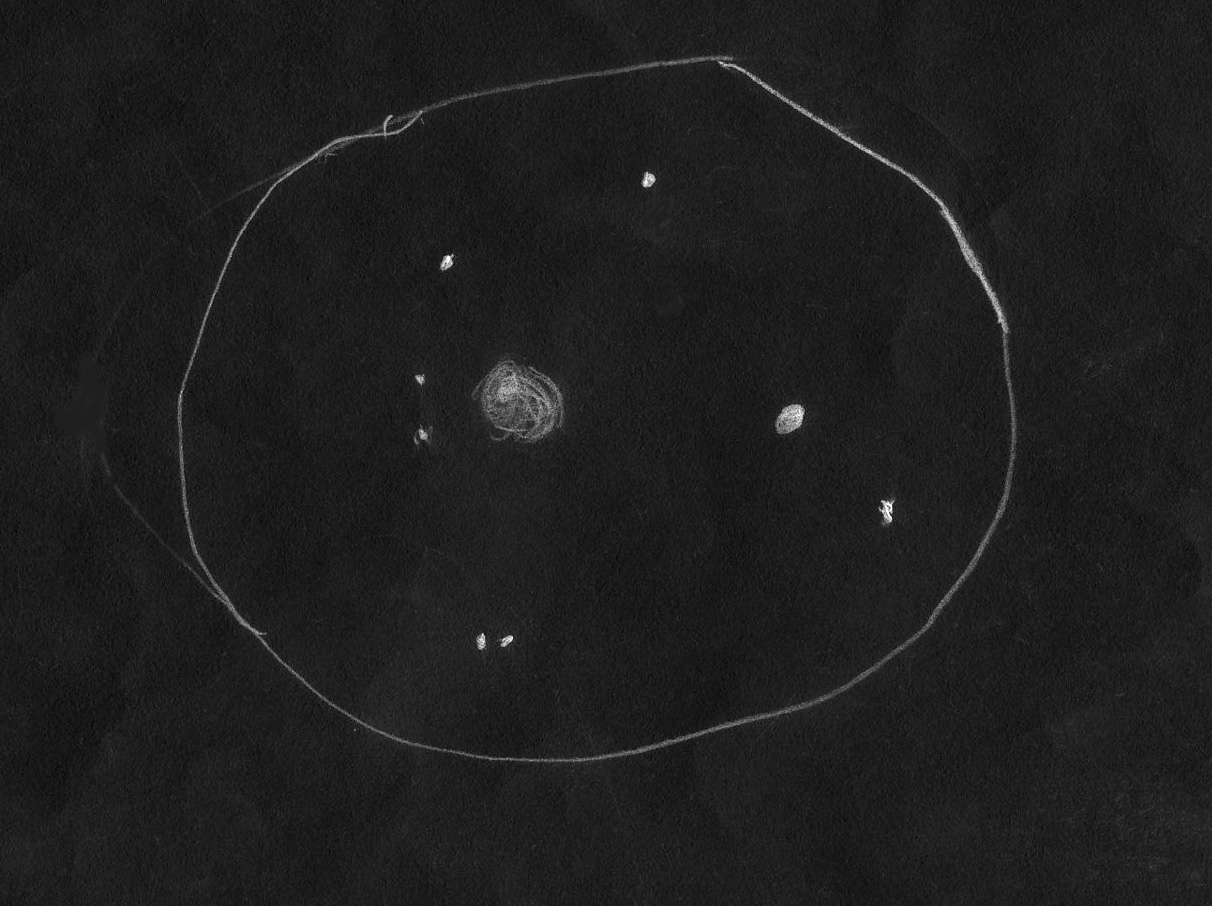

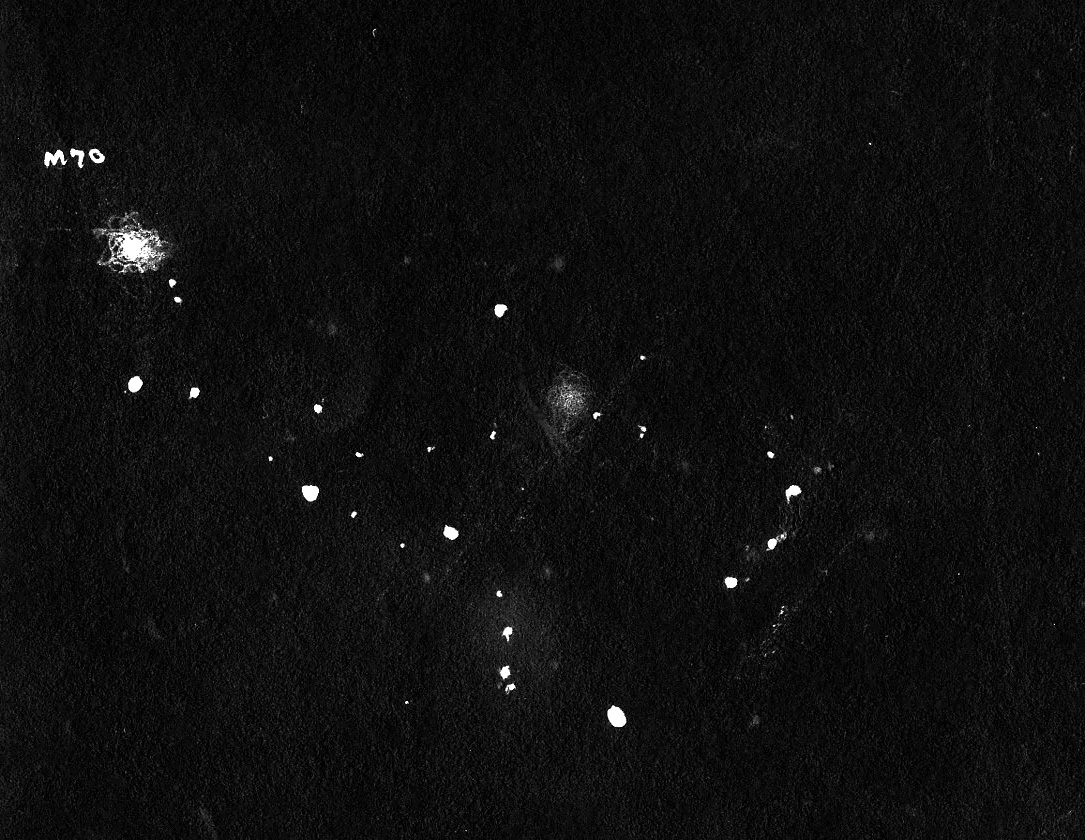

At-the-telescope sketches I made of the two most significant comet observations of my life, and that I am celebrating in "Ice and Stone 2020." Left: My first observation of Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka 1969g (no. 1) on the evening of February 2, 1970, through an 11-cm reflector. Right: Discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1 (no. 199) on the early morning of July 23, 1995, through the 41-cm reflector.

At-the-telescope sketches I made of the two most significant comet observations of my life, and that I am celebrating in "Ice and Stone 2020." Left: My first observation of Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka 1969g (no. 1) on the evening of February 2, 1970, through an 11-cm reflector. Right: Discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1 (no. 199) on the early morning of July 23, 1995, through the 41-cm reflector.

I plan to launch "Ice and Stone 2020" formally on January 1, 2020, and right now am very busy in writing the content and also in raising funds to help underwrite the effort. My plan is to have the program available on-line for educators and students around the world, and in keeping with the overall mission and spirit of Earthrise, I am making it entirely free of charge so that participants everywhere can access it. I am being reminded of the entire meaning of Earthrise at this very moment, since it was exactly twenty years ago this week that I journeyed to Iran with the "science diplomacy" delegation I led, and it was that trip, and subsequent efforts, that played a significant role in my decision to develop Earthrise.

Comet PANSTARRS has the distinction of being the first comet on my tally with a perihelion date in the decade of the 2020s -- something that almost seems surreal. Like the previous comet -- wherein I mentioned this essentially in jest -- Comet PANSTARRS' tally number is notable, in that "667" now puts me 2/3 of the way to 1000. I added tally entry no. 333 in March 2003, and if I were to maintain the same average pace that I have since that time, that would put me reaching comet no. 1000 sometime during the mid- to late 2030s -- at which time I would be in my upper 70s.

I have discussed "retirement" from time to time in these pages, with a potential timeframe of 2024 -- a date I have chosen in large part because it includes the "long range" comets on the "Upcoming Comets" page. This is by no means "cast in stone," and it is certainly conceivable that I might decide to continue on beyond that time -- although I may or may not decide to do so with the same intensity that I have been pursuing for the past couple of decades.

The primary deciding factor may well be how well my health continues to hold up -- or does not hold up. At this writing it has now been just slightly over a year since my hospitalization, and although I have recovered for the most part, some of the underlying health issues that contributed to that hospitalization are still there, and will likely remain indefinitely. It is quite obvious to me that I am not in as good a physical condition as I was even just a few years ago, and I no longer quite possess the energy that I used to have -- but I am nevertheless still here, and still plugging away at things. Emotionally, I am doing about the best I have done in several years; writing "Ice and Stone 2020" has given me a purpose that I find meaningful, my sons are doing well, and I finally have a good woman in my life.

For now, I am continuing along with observing comets, and with life in general, pretty much as I have all along, and I take each day as it comes. Depending upon how my health holds up, I will make any decisions about the future when that future gets here. I may or may not ever get to 1000 comets, but regardless of whatever happens, it's been a pretty good ride.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 July 31.44 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.4' coma, DC = 5-6 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

668. COMET 114P/WISEMAN-SKIFF Perihelion: 2020 January 14.09, q = 1.579 AU

For the second time this year, I have had to go over 3 1/2 months without adding a comet to my tally. Not only that, but this just-ended stretch is the longest period I have gone without a tally addition in 19 years. It hasn't been for lack of trying, though; I have attempted quite a few comets during this time, some of which I may still pick up at some point. There was also the Damocloid object A/2018 V3, which I managed to observe a handful of times during late August as a stellar 15th-magnitude object, around which time it was passing 0.37 AU from Earth; despite a retrograde orbit with an approximate period of 1340 years, it exhibited a completely stellar appearance in several images I took with the Las Cumbres Observatory telescopes, and as far as I know no one else detected any kind of cometary activity either. If at some point in the future some evidence comes to light that shows that it was in fact a weakly active comet, I will add it to my tally retroactively.

The comet that finally ended this long empty stretch happens to have been the first comet discovery to be announced after the birth of my older son Zachary. It was discovered in January 1987 by Jennifer Wiseman, at that time an undergraduate student from MIT working as a research assistant at Lowell Observatory in Arizona, on photographs that had been taken by Brian Skiff in late December 1986; they were then able to obtain confirming photographs shortly after the middle of January. I've mentioned Brian Skiff in connection to one of the comets I observed during "Countdown;" Jennifer Wiseman, meanwhile, has gone on to have a very successful career in astronomy, earning her Ph.D. in astronomy from Harvard in 1995 and presently being based at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, where she is the Senior Project Scientist for the Hubble Space Telescope. The comet was around 14th magnitude around the time of its discovery, and I attempted it a few times unsuccessfully with the 20-cm telescope I was using at the time; had I had the 41-cm telescope I would acquire a few months later I probably would have been able to see it.

Comet Wiseman-Skiff was found to be periodic, with an orbital period of a little over 6 1/2 years (presently 6.68 years). For the most part it has been a relatively nondescript, if nevertheless dependable, short-period object, that has been recovered on every subsequently return. It is possible that a meteor photographed in the Martian sky by the Spirit rover on March 7, 2004 may have been from this comet, during the course of a putative "Martian Cepheid" meteor shower. Meanwhile, I successfully observed the comet during its return in early 2000 (no. 274), when I followed it for two months and it reached a peak brightness near 13th magnitude, but the two intervening returns since then have been unfavorable. On the current return it was recovered on July 30, 2019, by Kevin Hills at the Tacande Observatory in the Canary Islands. I made my first attempt shortly after the mid-November full moon but couldn't quite see anything convincing, but when I tried again on the evening of November 22 I successfully spotted it as a very faint, diffuse, somewhat condensed object that exhibited the expected motion over the next 20 to 25 minutes.

The current return is very similar to the one in 2000, with the respective perihelion times being less than three days apart. The comet is presently located in eastern Andromeda two degrees southeast of the star Gamma Andromedae, and having gone through opposition near the end of October and being currently at its stationary point, over the next few weeks it travels towards the southeast through Triangulum and (starting in late December) Aries, and is closest to Earth (0.72 AU) in early December. It should brighten by a few tenths of a magnitude over the next three to four weeks, and while it should still be visually detectable at the start of 2020, I expect it to fade beyond visual range by about the end of January.

This will almost certainly be the last return at which I will observe Comet Wiseman-Skiff. The next two returns (perihelion passages September 2026 and May 2033) are relatively unfavorable, and while the return after those (perihelion mid-December 2039) is very favorable, with the comet's approaching to 0.57 AU of Earth, I somehow doubt I'll still be actively observing comets at the age of 81 even if I should still be alive then. But I have other endeavors that are keeping me occupied, including the "Ice and Stone 2020" program for which I just finished writing the content, and which will be going active in six weeks.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 November 23.08 UT, m1 = 14.3, 0.7' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

669. COMET P/SCHEILA P/(596) Perihelion: 2022 May 25.59, q = 2.452 AU

Prior to the 3 1/2-month-long gap that preceded my addition of the above comet to my tally, I had added two comets to my tally during the course of a single night. I did the same thing again at the end of the gap, when I added this object less than 40 minutes after I first saw the above comet. I suppose this could be considered a "cheap" addition, since it is not a comet per se but rather is an "active asteroid," having exhibited a single burst of cometary activity nine years ago after an apparent impact by a smaller asteroid. I discuss my rationale for including it as a "comet" for tally purposes in the entry for its retroactive addition (no. 623).

Scheila is bright enough such that it can be detected visually all around its orbit, at least when it is near opposition. I had added the previous "return" (no. 624) just seven hours after aphelion, and now, five years later, it has just gone through aphelion again. I made my final observation of the previous "return" on the evening of November 18 when it was just two days before aphelion, and after some nights of clouds (including our first winter storm of the season) I saw it again on the evening of November 22, two days after aphelion. It appeared as a stellar object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude.

Scheila is at opposition just before the end of November, and may brighten another one to two tenths of a magnitude before then. Afterwards it begins fading, and although it theoretically remains bright enough for me to detect for the first few months of 2020, I will probably not follow it beyond about the end of January. It is currently located in central Taurus three degrees north of the center of the Hyades star cluster and is slowly traveling westward, and will reach its stationary point -- 9 degrees west of its present location, and 2 1/2 degrees south-southeast of the Pleiades star cluster (M45) -- shortly before the end of January. By then it will should be about a magnitude fainter than it is now.

Scheila's next opposition will be in early February 2021, when it will be traveling through the constellations of Leo Minor and Lynx and should be near magnitude 13.5. It will be at opposition again in late May 2022 -- right around the same time it is at perihelion -- when it will be located slightly eastward of the "head" of the constellation Scorpius, and as bright as 12th magnitude. The next opposition will take place just before the end of September 2023, when Scheila will be in western Cetus and close to magnitude 13.5, and the one after that will be in late November 2024, when it will be in central Taurus very close to where it is now, and once again slightly brighter than 14th magnitude. Shortly thereafter, it is at aphelion again in early December, and then the next "return" will begin.

For at least the near-term foreseeable future, I expect to continue my current practice of observing Scheila once or twice a month around the times it is at opposition. I rather highly doubt that it will exhibit any additional cometary activity during these next five years, although I suppose one never knows, and theoretically it could surprise us at some point. In any event, by the time this "return" is done I should be near the "retirement" timeframe I have discussed elsewhere in these pages, and I guess we'll see what things are like for me then.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 November 23.12 UT, m1 = 13.8, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (October 16, 2020): After being in conjunction with the sun at the end of June, this one-time "active asteroid" has now emerged into the morning sky. I successfully observed it yesterday morning as a stellar object of 15th magnitude.

Scheila is currently located in northeastern Cancer and is traveling eastward at 15 arcminutes per day. It crosses into northern Leo -- near the "head" of that constellation -- shortly before the end of October, and passes through its stationary point in late December. When at opposition in early February 2021 it will be near the star Alpha Lyncis and should be near magnitude 13.5. Afterwards it will reach its other stationary point -- roughly six degrees west of its opposition position -- at the end of March and thereafter travels southwestward, crossing back into Leo a little after mid-May. Scheila should remain accessible for observations until June, by which time it will be starting to get low in the western evening sky and will have faded back to 15th magnitude.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 October 15.43 UT, m1 = 14.8, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

670. COMET 2I/BORISOV I/2019 Q4 Perihelion: 2019 December 8.55, q = 2.007 AU

Fifty years ago, on December 21, 1969, my very first comet, Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka 1969g, passed through perihelion at a heliocentric distance of 0.473 AU. It had been independently discovered by three Japanese amateur astronomers in mid-October, being around 10th magnitude at the time; it traveled southward, and around the time of perihelion passage was visible only from the southern hemisphere, as a naked-eye object close to 3rd magnitude. Thereafter it headed back north, becoming accessible from the northern hemisphere around mid-January 1970, around which time it became the first comet to be observed from space when NASA's Orbiting Astronomical Observatory 2 (OAO-2) mission observed it and detected a large ultraviolet cloud of hydrogen surrounding the coma. It had faded to 5th magnitude when I first saw it on the evening of February 2; I posted the at-the-telescope sketch I made of it that night in an earlier entry.

And now, on the 50th anniversary of that comet's perihelion passage, I have added the newest comet to my tally. In contrast to that first comet, this new one is an extremely faint object barely detectable at the extreme limit of visibility of my 41-cm telescope. Despite its faintness, however, from a scientific perspective this newest comet is "one for the ages". . .

The comet was discovered on August 30, 2019 by Gennady Borisov, an amateur astronomer in the Crimea who has specialized in finding faint comets at small solar elongations; he found his first one (no. 527) in July 2013 and as of this writing has discovered 9 of them, of which I have seen 7. At the time of its discovery this particular Comet Borisov was a faint object of 18th magnitude located at an elongation of 38 degrees in the morning sky, and initially there didn't seem to be anything unusual about it. However, as orbital calculations began to be performed these indicated something truly remarkable: the comet is traveling in an extremely hyperbolic orbit with an eccentricity of 3.4, which can only mean one thing. Comet Borisov is an interstellar comet, arriving within the solar system from "outside," i.e., from some other planetary system somewhere else in the Galaxy. It is the first confirmed example of an interstellar comet; while the object 1I/'Oumuamua, discovered by the Pan-STARRS program in 2017 (and which I discuss in a previous entry), was also an interstellar object, it never exhibited direct evidence of any cometary activity, and its true physical nature remains a mystery. Comet Borisov, in contrast, has been an obvious comet ever since its discovery, and also unlike 'Oumuamua, which was already receding from the sun and Earth at the time of its discovery and which accordingly was followed for less than three months before it became too faint to detect, Comet Borisov was still inbound when it was discovered and this has allowed it to be studied much more closely.

It has indeed been thoroughly examined by a variety of telescopes and instruments both on Earth and in space. Thus far it has behaved rather similarly to Oort cloud long-period comets in our solar system, and its chemical composition is also fairly similar to that of our solar system's comets. Data taken with the Hubble Space Telescope indicates that its nucleus is rather small, no more than about 1 km in diameter. A search for pre-discovery images identified several of these to as far back as December 13, 2018, when it appeared as a 21st-magnitude object in images taken during the course of the Zwicky Transient Facility program being conducted from Palomar Observatory in California; at that time the comet's heliocentric distance was 7.9 AU and the fact that it was exhibiting activity at that distance suggests the presence of volatile substances like carbon monoxide and/or carbon dioxide.

Comet Borisov has remained in the morning sky ever since its discovery, and has brightened slowly and steadily since that time. I began making visual attempts for it in late October, but up through early December these remained unsuccessful; at times I seemed to see very faint "suspects" but could never convince myself these were real. On my first attempt of the current dark run, on the morning of December 21, under exceptionally good sky conditions I managed to spot an extremely faint and tiny suspect of magnitude 14 1/2 that exhibited the expected motion over the course of the next hour, and on the following morning -- again under excellent sky conditions -- I was able to follow the comet for an hour and a half.

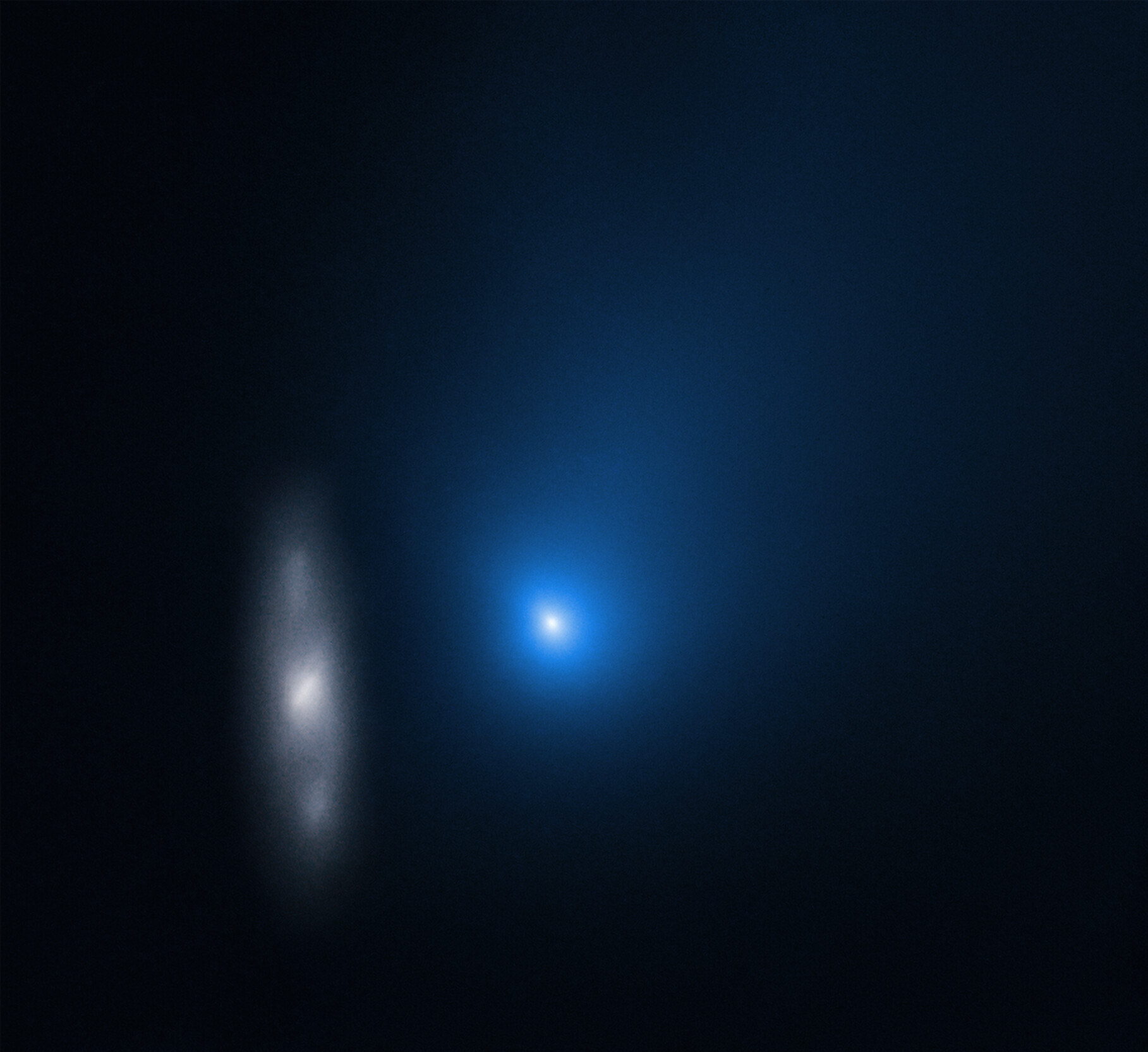

COMET 2I/BORISOV. Left: An image I took with the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas on December 21, 2019, two hours after my first visual sighting. This image was taken near the beginning of nautical twilight and the comet appears weaker than it would under darker conditions. Right: Image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope on November 16, 2019. The galaxy to the left of the comet is 2MASX J10500165-0152029. Courtesy NASA/ESA/David Jewitt (UCLA).

COMET 2I/BORISOV. Left: An image I took with the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas on December 21, 2019, two hours after my first visual sighting. This image was taken near the beginning of nautical twilight and the comet appears weaker than it would under darker conditions. Right: Image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope on November 16, 2019. The galaxy to the left of the comet is 2MASX J10500165-0152029. Courtesy NASA/ESA/David Jewitt (UCLA).

Although receding from perihelion, Comet Borisov is still approaching Earth, with a minimum distance of 1.937 AU taking place on December 28; thus, barring anything unusual happening, it is very probably as bright right now as it is going to get. Indeed, it is rather possible that I will not be able to observe it again; a series of winter storms is expected to pass over New Mexico over the course of this next week, and meanwhile the comet, already at a declination of -28 degrees when I observed it, is traveling southward fairly rapidly. In addition to its likely fading, it drops below my southern horizon shortly after mid-January 2020, and enters southern circumpolar skies in early February.

A backwards extrapolation of Comet Borisov's orbit indicates that it has arrived in our solar system from the direction of southeastern Cassiopeia a couple of degrees north-northwest of the Double Cluster in Perseus, near the galactic plane. Although some attempts have been made to identify a possible "origin point" for the comet, nothing conclusive has been found, and it is rather possible that it has been wandering the Galaxy for hundreds of millions, perhaps even billions, of years. As it recedes from the inner solar system it should be followed by large telescopes in the southern hemisphere and in space for perhaps up to a year or so after its discovery, after which it will likely become too faint to detect. Comet Borisov will depart our solar system in the direction of western Telescopium close to the globular star cluster NGC 6584, again fairly near the galactic plane. It should continue to wander the Galaxy for many hundreds of millions, to billions, of years to come -- possibly passing through other planetary systems from time to time -- and I feel truly privileged to have been able to see it -- even if only briefly, and barely -- during its ephemeral passage through our solar system.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 December 21.44 UT, m1 = 14.6, 0.3' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center