TALLY ENTRIES 671-680

A new year . . . and a new decade. After quite a few upheaveals in my life, and a lot of "ups" and "downs" -- many of which I've described in previous entries -- during the just-completed decade of the 2010s, things seem to have settled down into a rather quiet normality for me as the 2020s begin, and overall I am reasonably content. Among other things, the "Ice and Stone 2020" educational program that I spent a good part of last year developing is underway, and while I have recently found it necessary to conclude the weekly "In Our Skies" newspaper column that I have written for the past 25 years, there are some other potential opportunities that I may be exploring within the not-too-distant future.

On the other hand, at my current age and especially within the context of the health issues I have encountered over the past couple of years, I begin the 2020s with the very real possibility that I will not be able to complete this decade at the activity level, both astronomical and otherwise, that I presently enjoy. It is entirely possible that at some point I may be forced to curtail my astronomical observing activities, and indeed I have discussed a potential "retirement" timeframe of mid-decade elsewhere on this web site. I have also had to come to terms with the potential possibility that I may not survive until the end of the decade. But, that part of my story, if that is indeed what it is, has not been written yet, and for the time being I am therefore continuing to take life as it comes one day at a time, and among many other things that means that I am continuing to observe comets.

Comet ATLAS turns out to be a very interesting object, for it appears to be the fourth member of a "family" of comets that have been been appearing over the past three decades and that share almost identical orbits.The first member of this "family," and what was apparently the primary component, was Comet Liller 1988a (no. 116), which became a dim naked-eye object

with a peak brightness between 5th and 6th magnitude during March and April 1988. (By an interesting coincidence, my first observation of Comet ATLAS came exactly 32 years, to the day, after my first observation of Comet Liller.) After 8 1/2 years, the second comet, Comet Tabur C/1996 Q1 (no. 219), appeared (with the orbital similarity to that of Comet Liller being first pointed out by German amateur astronomer Jost Jahn); although clearly fainter intrinsically than Comet Liller, it came closer to Earth, and also experienced a pre-perihelion outburst which briefly made it as bright as magnitude 4.5. This was apparently a disintegrative outburst, for afterwards Comet Tabur essentially dispersed away and only a vague cloud of debris was visible after perihelion. Then, after over 18 years a third member appeared, Comet SWAN C/2015 F3 (no. 569), with the orbital relationship being first pointed out by Worachate Boonplod in Thailand. Comet SWAN was significantly fainter than the previous two comets, never being brighter than about 10th magnitude, but in contrast to Comet Tabur it survived perihelion passage -- indeed, it was not even detected in images taken with the Solar Wind ANisotropies (SWAN) ultraviolet telescope aboard SOHO until just before perihelion -- although it did fade away fairly rapidly thereafter. (For what it's worth, I played a role in the confirmations of both Comet Tabur and Comet SWAN.) Detailed calculations carried out after the discovery of Comet SWAN indicate that the comets had previously returned around 945 B.C., with Comets Tabur and SWAN splitting from Comet Liller around that time.

The three previous members of the Comet Liller "family." Left: Wide-field view of Comet Liller 1988a (no. 116) on April 17, 1988 from Parkton, North Carolina. Courtesy Jim Skinner. Center: Comet Tabur C/1996 Q1 (no. 219) on October 12, 1996. The edge-on spiral galaxy M108 is to the comet's upper right, and the "Owl Nebula" M97 is in the lower right. Courtesy Gerald Rhemann and Franz Kersche in Austria. Right: Comet SWAN C/2015 F3 (no. 569) on March 26, 2015. Courtesy Francois Kugel in France.

The three previous members of the Comet Liller "family." Left: Wide-field view of Comet Liller 1988a (no. 116) on April 17, 1988 from Parkton, North Carolina. Courtesy Jim Skinner. Center: Comet Tabur C/1996 Q1 (no. 219) on October 12, 1996. The edge-on spiral galaxy M108 is to the comet's upper right, and the "Owl Nebula" M97 is in the lower right. Courtesy Gerald Rhemann and Franz Kersche in Austria. Right: Comet SWAN C/2015 F3 (no. 569) on March 26, 2015. Courtesy Francois Kugel in France.

And now, as was first pointed out by Dutch amateur astronomer Reinder Bouma, with Comet ATLAS we apparently have the fourth member of the Comet Liller "family." It is presently located in the evening sky, at an elongation of 50 degrees in eastern Aquarius near a declination of -15 degrees; it is traveling almost due northward at roughly 45 arcminutes per day, crossing into Pisces and then going north of the Celestial Equator in early February, then into eastern Pegasus two weeks later and into Andromeda in mid-March around the time of perihelion passage. It is in conjunction with the sun -- 37 degrees north of it -- a few days later, then crosses into western Cassiopeia just after the beginning of April; shortly thereafter it enters northern circumpolar skies while traversing the western portion of the "W" of that constellation. The comet reaches a peak northerly declination of +82.8 degrees on May 2, at which time it is also closest to Earth (1.09 AU) and thereafter heads southward, passing through the western part of the "bowl" of the Big Dipper during the fourth week of May and exiting northern circumpolar skies thereafter. It remains in the northern's hemisphere evening sky for several weeks afterward.

Ostensibly, more and more distant cometary fragments tend to have fainter and fainter intrinsic brightnesses, and thus we might expect that Comet ATLAS is even fainter, intrinsically, than Comet SWAN. My initial observation of Comet ATLAS suggests, however, that it has at least the same intrinsic brightness as Comet SWAN, and if that is indeed true then it might become as bright as 10th magnitude during March and April. On the other hand, the behavior of other fragmented comets, including Comet Tabur, suggests that any of several things could happen; it could undergo one or more significant outbursts and could briefly become quite bright, or it might just disintegrate and fade away as it approaches perihelion, or both, or something else entirely. We will just have to wait and see what the comet does as it makes its way through the inner solar system.

As for whether or not there are more members of this "family" that are still on the way in and that might appear during the years and decades to come, time will tell. However, unless any such comets happen to arrive within the relatively near future, I will probably have to leave any observations of these objects to some successor of mine.

A piece of trivia: when the IAU went to the new comet designation scheme at the beginning of 1995, it retroactively assigned new-style discovery designations to all pre-1995 comets in the manner that they would have been assigned had the scheme been in operation then. Within that context, with Comet ATLAS I have now observed the "9 Y1" comet for six consecutive decades, from the 1960s through the 2010s.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 January 14.08 UT, m1 = 12.4, 2.1' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (April 18, 2020): Perhaps a little surprisingly, Comet ATLAS held its own and brightened steadily, and was near 9th magnitude when it passed through perihelion in mid-March. It continued to hold its own afterwards, and then, in mid-April -- a full month after its perihelion passage -- it seems to have undergone a small outburst. When I observed it this morning it was easily detectable in 10x50 binoculars as an object of 8th magnitude -- which, curiously, makes it the brightest comet currently visible in the northern hemisphere's skies.

Whether or not this is just a typical outburst that several comets have been observed to undergo, or instead is the first visible event of a disintegration process, remains to be seen, and time will tell. Since Comet ATLAS remains in northern circumpolar skies for the next few weeks it should be relatively easy to keep track of.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 April 18.45 UT, m1 = 7.8, 6' coma, DC = 4 (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (December 8, 2023): A little over 3 1/2 years after the appearance of Comet ATLAS, a fifth member of the Comet Liller "family" appeared. Comet Leonard C/2023 V5 was discovered on November 6, 2023 by Greg Leonard during the course of the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona, and just as with Comet ATLAS, within fairly short order Dutch amateur astronomer Reinder Bouma suggested it as a new member of the Liller "family." Subsequent orbital calculations have since confirmed this, with a perihelion passage (0.845 AU) taking place on December 14, 2023. On November 4, i.e., two days before its discovery, the comet had passed 0.22 AU from Earth.

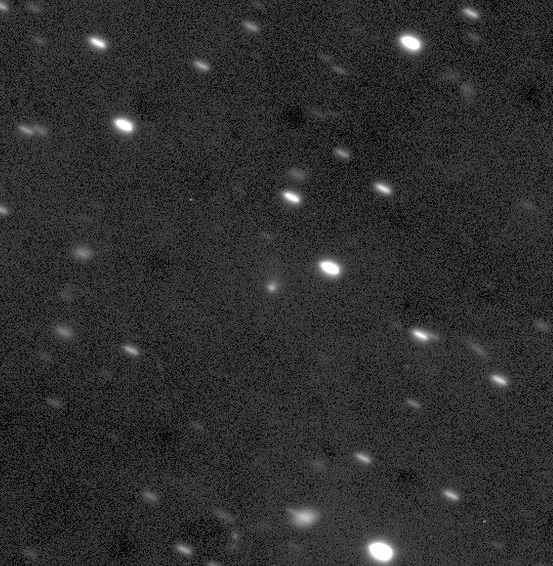

Intrinsically, Comet Leonard appears to be a very minor member of the Liller "family," for despite its proximity to Earth it was only about 18th magnitude at the time of its discovery. A series of images I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network shortly after its discovery show it as a faint, somewhat condensed object with a hint of a larger and vague outer coma, however another set I obtained five days later show the comet only as a very faint, uncondensed and somewhat elongated "blur." After the full moon I took another set of images on the night of December 2-3 but could not find it, and, at this writing, there have been no other reported observations during this dark run; indeed, the last reported observations were made only nine hours after the set of images I obtained on November 11. It appears likely, then, that the comet has disintegrated as it approached perihelion. (For what it's worth, I never attempted the comet visually.)

Images of Comet Leonard C/2023 V5 I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. Both images are 5-minute exposures. LEFT: November 6, 2023, from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. I have enhanced the contrast to bring out what may be a very faint outer coma. RIGHT: November 11, 2023, from the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. The last reported observations of this comet were made only nine hours later.

Images of Comet Leonard C/2023 V5 I obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. Both images are 5-minute exposures. LEFT: November 6, 2023, from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. I have enhanced the contrast to bring out what may be a very faint outer coma. RIGHT: November 11, 2023, from the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. The last reported observations of this comet were made only nine hours later.

672. COMET IWAMOTO C/2020 A2 Perihelion: 2020 January 8.32, q = 0.978 AU

The first confirmed comet discovery of the 2020s was found on CCD images taken January 8, 2020, by Japanese amateur astronomer Masayuki Iwamoto, who has discovered three previous comets, all of which I have seen, including his most recent one (no. 658). The comet was very low in the eastern sky at dawn, and with only two positions -- barely over a minute apart -- available, and moreover with this being just before full moon, it remained unconfirmed for several days thereafter. Then, on January 13 Gennady Borisov in the Crimea -- another individual who has appeared on my tally several times, including with his most remarkable recent discovery (no. 670) -- accidentally re-discovered it. With these new observations now available other observers quickly began making astrometric observations of the comet, which in turn allowed a preliminary orbit to be calculated. Armed with this

information, I successfully located it visually on the morning of January 14, although in the bright moonlight I couldn't tell much other than the fact that it was "there." In a somewhat darker sky four mornings later I could easily detect it as a vague and diffuse object of 12th magnitude. (Incidentally, with the addition of the previous comet on the evening of the 13th this marks the 36th occasion during which I have added two or more comets to my tally on the same night, and this is the fifth time I have done so by adding the first comet during the evening hours (i.e., before local midnight) and the second one during the morning hours, after local midnight.)

Comet Iwamoto is traveling in a relatively steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 121 degrees) and has approached the inner solar system from the south and from behind the sun, being in conjunction with the sun in mid-December and being at perihelion at the time of its discovery, at which time its elongation was still a relatively low 34 degrees. It is currently located in northern Ophiuchus -- the elongation having now increased to 45 degrees -- and is heading primarily northward, and over the next few weeks it travels through Hercules, Lyra -- passing half a degree west of the bright star Vega on February 7 -- and Draco; it enters northern circumpolar skies during the third week of February (being closest to Earth, 0.92 AU, on the 21st), is at opposition at the end of February, and is at its highest north declination, +78.2 degrees, during the first few days of March. Afterwards it travels southeastward through Cassiopeia, Camelopardalis, and Auriga, where it remains until near the end of May. The comet may brighten by perhaps a half-magnitude or so between now and early February but thereafter will probably fade beyond visual range by sometime in March.

Among the various events happening in the world right now (which I will mostly refrain from commenting on at this time), I have been saddened by the recent death (on January 7) of Neil Peart, drummer and lyricist for the Canadian rock band Rush, one of my favorite bands. I had the privilege of seeing Rush perform live in concert at Pan Am Center in Las Cruces, New Mexico in January 1992, just a few days after I had returned from a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Atlanta, Georgia, during which I had presented the results of my Ph.D. dissertation and which had, to my delight, been rather warmly received. Several years ago the members of Rush gave me permission to use one of their songs for an audio/visual project I was developing to raise funds for Earthrise at the time, and in the meantime all three members (Peart, vocalist/bassist/keyboardist Geddy Lee, and lead guitarist Alex Lifeson) have had asteroids named for them. As I contemplate my own life, and my own mortality, the lyrics of their songs like "Dreamline" and "Time Stand Still" resonate ever more powerfully with me.

CONFIRMING OBSERVATION: 2020 January 18.52 UT, m1 = 11.8, 2.6' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

673. COMET ATLAS C/2019 Y4 Perihelion: 2020 May 31.02, q = 0.253 AU

Fifty years ago this month, on the evening of February 2, 1970, I observed my very first comet, Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka 1969g; I included the at-the-telescope sketch I made of that comet that night in an earlier tally entry. I had hoped to mark the anniversary by observing at least one comet, but unfortunately the skies were cloudy that particular night; I did, however, manage to observe Comet PANSTARRS C/2017 T2 (no. 667) -- presently about 10th magnitude -- in a somewhat moon-brightened sky the following evening.

I'm under no illusions that I'll be keeping this up for another 50 years, but for at least the near-term foreseeable future I expect to continue observing whatever comets that come by and are bright enough to see. My first tally addition of my second half-century of comet observing is a rather interesting object that was discovered by the ATLAS program in Hawaii on December 28, 2019, at which time it was a very dim object of 19th magnitude. Ever since then I've been imaging it on a semi-regular basis with the Las Cumbres Observatory network and it has brightened fairly rapidly, and on an image I took on February 15 it seemed bright enough to be worth a visual attempt, however my attempt on the evening of the 16th was unsuccessful. Images that were taken by other observers over the next several nights, and even a couple of reports of visual observations, indicated that the comet was continuing to brighten, and after enduring several nights of cloudy and stormy weather I finally had another clear night on the evening of February 23 and clearly detected it as a diffuse and somewhat condensed object slightly fainter than 13th magnitude.

Two recent Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4, illustrating its rapid rise in brightness; both images are 5-minute exposures. LEFT: February 15, 2020, from Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands. RIGHT: February 27, 2020, from McDonald Observatory in Texas. Several background galaxies are visible in the image.

Two recent Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4, illustrating its rapid rise in brightness; both images are 5-minute exposures. LEFT: February 15, 2020, from Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands. RIGHT: February 27, 2020, from McDonald Observatory in Texas. Several background galaxies are visible in the image.

Comet ATLAS' small perihelion distance certainly brings attention. However, what really makes this comet interesting is the fact that its orbit is essentially identical to that of Comet 1844 III (new style designation C/1844 Y1), which is usually referred to as the Great Comet of 1844. That object was discovered from the southern hemisphere in December 1844 just after it had passed through perihelion, and which at its brightest was close to magnitude 0 and which exhibited a bright tail with a maximum length of about 10 degrees. The two comets are almost certainly fragments of an earlier comet which had split, presumably somewhere around the time of its previous return some 4000 to 4500 years ago.

At this time Comet ATLAS is entering northern circumpolar skies, being presently located in the southwestern "corner" of the "bowl" of the Big Dipper in Ursa Major, and traveling towards the northwest at close to 45 arcminutes per day. It is at opposition in early March and reaches a maximum northerly declination of +68.6 degrees at the end of that month, at which time it crosses into Camelopardalis. The comet continues traveling westward for some time thereafter, finally dropping south of declination +60 degrees at the beginning of May and entering Perseus a little less than two weeks later. From that point it begins a rapid southward plunge in the evening sky as it approaches perihelion, with the elongation dropping below 30 degrees on May 16 and with its being in conjunction with the sun (24 degrees north of it) on May 20. The final approach to perihelion will take place in the dawn sky, with the comet's passing 12 degrees due west of the sun around the time of perihelion passage. Thereafter it becomes accessible from the southern hemisphere in the morning sky, although by then it is on the far side of the sun from Earth and remains at a small elongation for some time, with this not exceeding 25 degrees until early July and not exceeding 30 degrees until three weeks later.

The potential for a decent display, and naked-eye visibility, from Comet ATLAS certainly exists, although the inherent uncertainty in making predictions of cometary brightnesses makes any projections quite problematical. In general, trailing fragments -- as Comet ATLAS apparently is -- tend to be smaller and thus fainter than leading fragments, so at face value there is no reason to think that it will become as bright as the 1844 comet. It is conceivable that Comet ATLAS itself could fragment, and thus undergo a surge in brightness similar to that of Comet West 1975n (no. 20) in 1976, but it is also conceivable that it could completely disintegrate and disperse, as did Comet ISON C/2012 S1 (no. 529) in 2013. One potential bit of good news is that, if Comet ATLAS should be a dust-rich comet and undergo a significant amount of dust release as it approaches perihelion, during that approach to perihelion it will be between Earth and the sun -- with a minimum distance from Earth of 0.78 AU taking place on May 23 -- and thus will be appearing at high phase angles (in excess of 130 degrees for a few days) and accordingly there could be some noticeable enhancement of its brightness due to forward scattering of sunlight.

All of this is just speculation, of course. My own "gut feeling" is that we will probably see a naked-eye comet, but not anything that could be considered a "Great Comet." But, I could be wrong . . . All we can really do is see what this comet reveals to us over the coming three to four months.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 February 24.22 UT, m1 = 13.3, 0.8' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (March 19, 2020): Comet ATLAS has continued its trend of rapid brightening; as of the middle of March it has reached 9th magnitude and I can faintly detect it with 10x50 binoculars. At face value this might suggest that we may well be in for a good show when the comet reaches perihelion in late May, although in all likelihood the rate of brightening will decrease within the not-too-distant future. Nevertheless, unless the recent brightening is due to the beginnings of a disintegration process -- and at present there is no evidence that suggests this is the case -- Comet ATLAS should reach naked-eye brightness during May.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 March 15.19 UT, m1 = 9.3, 7.5' coma, DC = 3 (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (April 10, 2020): By late March I was measuring a brightness of magnitude 8.5 for Comet ATLAS. However, in early April several institutions and observers were beginning to report that the comet was fading, and images of the comet's central region were suggesting that the nucleus might be splitting up. With the bright moonlight then it would have been all but pointless to have made any visual observations, however once I had a dark sky again -- last night -- I could tell for myself that Comet ATLAS has indeed faded significantly from before; moreover, instead of a bright, distinct central near-condensation, the brighter central region was much less distinct, was elongated in the tailward direction, and at best appeared somewhat "grainy." CCD images that I'm seeing distinctly show that the nucleus is indeed fragmenting.

It appears, then, that the potential bright show we thought we might get from Comet ATLAS is not going to happen. It might remain visible for some time yet, but will likely continue fading and diffusing out. There may be nothing left of it by the time it reaches perihelion passage.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 April 10.12 UT, m1 = 9.8, 4.5' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (May 3, 2020): Comet ATLAS is the "Ice and Stone 2020" "Comet of the Week" this week. Within that presentation are a couple of relatively recent images I have taken with the Las Cumbres Observatory network that illustrate its fading and change in appearance, as well as a recent image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope that shows several of the individual nuclear fragments.

Although thus far the comet's visual brightness has been holding somewhat steady at around 10th magnitude, during my most recent observations it has appeared as little more than an elongated "smear" of light. With bright moonlight now in the evening sky I am unable to obtain any more meaningful visual observations of it, and it will be close to another week before I can do so; whether or not there will be anything left to see then is something I will find out at that time. In any event, it now appears all but certain that Comet ATLAS will not be putting on any kind of bright display as it makes its final approach to perihelion.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 April 26.18 UT, m1 = 10.2, 5' x 10' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

674. COMET LEMMON C/2019 U6 Perihelion: 2020 June 18.82, q = 0.914 AU

When the IAU introduced its present comet designation scheme at the beginning of 1995, it included prefixes to denote the broad category that the comet in question belongs in, primarily "C" for long-period comets and "P" for short-period comets. A few other prefixes, less commonly used, were introduced as well; one of these was "A," originally intended to be used for objects that were reported as (and designated as) comets, but later found out to be asteroids. In reality, this scenario is quite rare, although there are a couple of historical examples. Within the recent past the IAU has taken to assigning the "A" prefix to objects in obvious long-period cometary orbits which nevertheless do not exhibit cometary activity; these are a subset of the population of objects called "Damocloids" and are likely "extinct" comets. To date I have visually observed one such object, this being A/2018 V3 which I discuss in a previous entry and which has never exhibited any kind of activity that could be considered "cometary."

A handful of these "A/" objects do end up showing cometary activity at some subsequent point; in most (although not necessarily all) such cases the IAU has re-designated these with the appropriate prefix (usually "C"). One such example is this object, which was discovered by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona on October 31, 2019; at that time, being located at a heliocentric distance of 3.46 AU, it appeared as a stellar object of about 20th magnitude. The somewhat small perihelion distance suggested to me that it might eventually exhibit cometary activity, and, indeed, when I began imaging it with the Las Cumbres Observatory telescopes near the end of December it was already doing so. It has continued to exhibit cometary activity, and has also brightened, in various images I have taken since then, and in images taken by other observers elsewhere, and after reading of a successful visual observation in mid-March by observer Michael Mattiazzo in Australia I successfully detected it on the evening of March 14 as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude. It appears distinctly cometary on an LCO image I took two days later, and shortly after that -- through thin clouds -- I again successfully observed it visually.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of A/2019 U6. Left: December 25, 2019, with the 1.0-meter telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory. Right: March 17, 2020, with a 40-cm telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. This was taken just two hours before my second visual observation.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of A/2019 U6. Left: December 25, 2019, with the 1.0-meter telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory. Right: March 17, 2020, with a 40-cm telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. This was taken just two hours before my second visual observation.

The comet is currently located in eastern Eridanus approximately one degree east of the star Tau-9 Eridani, low in my southwestern sky after dusk. It is traveling slowly towards the east-northeast, and I will lose it soon; observers in the southern hemisphere, meanwhile, should be able to keep tracking it as it travels through Eridanus, Lepus, Canis Major, Puppis, Hydra, and Sextans. By the end of June -- at which time it is closest to Earth (0.83 AU) -- it will have traveled far enough north such that I will be able to observe it again, and over the next few weeks it continues traveling towards the east-northeast through Leo and Virgo -- crossing through the center of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies during the fourth week of July -- and Coma Berenices, then into Bootes in early August -- passing just over a degree north of the star Arcturus on August 14 -- and into Serpens Caput at the beginning of September and Hercules during the last week of that month. As far as its brightness is concerned, this is difficult to predict, but based upon its current appearance and behavior a peak brightness near 10th magnitude during the latter part of June is perhaps reasonable, with its remaining detectable visually until sometime in August or September.

At this writing A/2019 U6 is still "officially" an "asteroid" and it has not been formally named, although since it is clearly cometary in nature I feel entirely justified in adding it to my tally as a "comet." At some point in the future the IAU will likely re-designate it as a "comet," and I will make note of that fact at that time.

These observations are coming at a rather "interesting" time in history, as the worldwide coronavirus pandemic has now shut down much of modern society. Vickie and I live in a rather isolated rural environment and thus are relatively safe, and even though due to my age and the recent health issues I have been experiencing I am perhaps in somewhat of a "high risk" situation, I am otherwise healthy and am doing OK. (I do have concerns for my sons, who both live in higher-population environments, but both of them are taking appropriate steps to increase their level of safety.) I continue to be able to make cometary and other astronomical observations, and I am continuing with endeavors like "Ice and Stone 2020" without any significant issues. At some point we will get through all this, and the surrounding universe will still be there for us.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 March 15.12 UT, m1 = 13.2, 1.4' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (March 26, 2020): The IAU has now formally re-designated this object as a comet and has officially assigned it the name "Lemmon." I have modified the title of this entry accordingly, but have left the rest of the above original text intact.

After several nights of clouds, I was finally able to obtain another observation of this comet last night; it has brightened some since last week. It is now quite low in my southwestern sky after dusk, and with the moon now set to enter the evening sky this was very probably my last observation of the comet for about three months. Observers in the southern hemisphere should still be able to continue following it as it approaches perihelion.

On an unrelated note . . . Shortly before I wrote this update Vickie, her father (who is visiting), and I felt a small earthquake. It turns out to have been epicentered some 200 km east-southeast of here, near the town of Mentone, Texas, with a magnitude of 4.7 on the Richter scale. I experienced a couple of earthquakes during the period of time when I lived in southern California during the early- to mid-1980s, and another one when I visited there some years ago, but this is the first earthquake I have felt during all the years I have lived in New Mexico.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 March 26.11 UT, m1 = 12.4, 1.5' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (May 16, 2020): While Comet Lemmon has been inaccessible for me for over a month and a half now, observers in the southern hemisphere have continued to be able to observe it, and according to them it has brightened quite dramatically within the recent past, with most of the recent reports indicating a present brightness near 8th magnitude. While there is no real reason to believe that the comet will continue this rapid rate of brightening up through perihelion passage, it nevertheless appears distinctly possible that it might be somewhere around 6th magnitude -- and thus conceivably visible to the unaided eye -- when I am finally able to observe it again near the end of June. As described above, the viewing geometry is relatively favorable for several weeks thereafter, and . . . we'll see what happens.

UPDATE (June 30, 2020): After three months during which time Comet Lemmon was visible only from the southern hemisphere, it has finally become accessible again from my location. I successfully observed it last night, very low in my southwestern sky during dusk, when it was 7th magnitude; in the twilight and moonlight it was a difficult object in 10x50 binoculars, but well visible in the 41-cm telescope, and I could even detect about 10 arcminutes of a broad, featureless tail towards the southeast. As I described above, during the coming weeks the comet will continue to climb higher into the evening sky; since it is now two weeks past perihelion and was just closest to Earth, it will probably fade gradually, although I expect it to remain visible in binoculars for at least another month.

Meanwhile, the southern hemisphere now has exclusive visibility of another moderately bright comet: Comet 2P/Encke, which passed through perihelion on June 25 (heliocentric distance 0.337 AU). Prior to perihelion it was on the far side of the sun from Earth and not visible, although it did spend a few weeks in the field of view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO; it never became bright enough to be detected, however. Just within the past day or so, observers in the southern hemisphere successfully picked it up low in twilight near magnitude 7 1/2, and over the next few weeks it climbs higher into their evening sky as it recedes from the sun and fades; it is closest to Earth (0.62 AU) on July 30. Theoretically it becomes accessible from my location by early August, however historically this comet tends to fade and diffuse out fairly rapidly as it recedes from perihelion, and it will probably be too faint for me to detect once I am able to access it.

I discuss this comet in write-ups during its returns in 2007 (no. 402) and 2013 (no. 531), and I also successfully observed it during its return in 2017 (no. 610). While it's likely I will miss it this time around, it will be easily accessible in the northern hemisphere's morning sky during its next return in 2023 (perihelion October 22) and, provided that I am still active in observing comets at that time, I should once again be able to see Comet Encke on what would be my 13th observed return.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 June 30.14 UT, m1 = 6.9, 5' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x; twilight, moonlight)

675. COMET 246P/NEAT Perihelion: 2021 February 22.82, q = 2.864 AU

As I write these words, the global coronavirus pandemic continues to wreak its havoc on the people of Earth. Vickie and I are perhaps less affected than some, since we live in a rural area and are thus rather isolated to begin with; her father, meanwhile, has been staying with us for the past month, which has been quite fortunate since the retirement home where he resides has had at least one positive incident of the virus and thus is currently on total lockdown. I continue to remain busy, primarily in keeping up with the work involved in "Ice and Stone 2020," and, certainly, I continue to observe the comets that are around. (Several of the Las Cumbres Observatory sites are closed, although a couple of them remain open and I can still obtain images when I feel they're necessary.) For a while it looked like Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673) was on track to become quite bright, possibly even "Great," towards the latter part of May, but it has now started to show clear signs of disintegration and has been fading, and thus it now appears that that potential bright showing isn't going to happen. In the meantime, there have been a couple of recent comet discoveries that possibly might become bright within the next two to three months, and . . . we'll see.

Amongst the various bright (and potentially bright) comets, I've just added a faint one to my tally. It's a dim periodic object that was discovered in March 2004 by the NEAT program, and I managed to obtain a handful of observations of it (no. 351) during that discovery return. I observed it again during the subsequent return in 2013 (no. 502), and I discuss it in some detail in that tally entry. On the present return it was recovered on December 16, 2018 by the Pan-STARRS program in Hawaii, and independently late that month by American amateur astronomer Jonathan Tuten who was utilizing a remotely-controlled telescope at Slooh Observatory in the Canary Islands. I began making attempts for it in early March 2020 but for the next month never saw anything convincing, but on the evening of April 10 I detected an extremely faint -- slightly fainter than 14th magnitude -- tiny object that I was able to confirm visually the following evening as well as with a set of Las Cumbres Observatory images.

The geometry of the current return is rather similar to that of 2013. The comet was at opposition just after the beginning of April and is now traveling slowly westward through southern Coma Berenices; it will pass through its stationary point slightly before the end of May when it will be located in the northern region of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies, after which it will begin turning towards the southeast as it passes 20 arcminutes west of the galaxy M88 in early June and similar distances west of the galaxies M89 and M58 later that month. I suspect it will fade beyond my visual range sometime during this period.

After conjunction with the sun in November, Comet NEAT begins emerging into the morning sky by about February 2021, en route to its next opposition in early July; along the way it will be traveling through rich Milky Way star fields in Sagittarius and will pass 15 arcminutes north of the open star cluster M21 just after mid-February and half a degree north of the bright globular star cluster M22 just before mid-March. It should be a half- to a full magnitude brighter than its present brightness during the weeks around opposition, although it will still be in relatively rich Milky Way star fields (and also around a declination of -30 degrees) during that time and thus may not be as easy to observe as it might otherwise be. After opposition it should start fading, and I will probably lose it by sometime in August or September.

While I have managed to see this particular Comet NEAT on each of its observed returns thus far, that will be coming to an end after this return. Throughout most of the 20th Century the comet had traveled in a significantly larger orbit with a period of 9.8 years and a perihelion distance near 3.8 AU, however an approach to Jupiter (0.35 AU) in July 2001 placed it into its current 8-year orbit with the smaller perihelion distance, which in turn helped make its discovery possible three years later. On its way out from perihelion this time around the comet will again approach Jupiter (0.53 AU) in July 2024, and that encounter will place it back into a larger orbit with a period of 9.1 years and a perihelion distance of 3.5 AU, where it will remain throughout the rest of the 21st Century. While it will likely still be recovered at future returns, it will remain much too faint for me to detect visually even in the best of circumstances.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 April 11.19 UT, m1 = 14.3, 0.3' coma, DC = 6-7 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (April 10, 2021): After its conjunction with the sun late last year, Comet NEAT began emerging into the morning sky earlier this year, and on my first post-conjunction attempt for it, on the morning of April 9, I successfully detected it as a very small and faint moderately condensed object slightly fainter than 14th magnitude.

At present the comet is located in eastern Sagittarius some 3 1/2 degrees northeast of the star Sigma Sagittarii (in the "handle" of the "teapot"), and traveling slowly towards the east-southeast. Over the next few weeks it curves more directly southward, and after passing through its stationary point (five degrees southeast of its present position) in late May it starts traveling towards the southwest; when at opposition in early July it will be 3 1/2 degrees south-southeast of the star Zeta Sagittarii (also in the "handle"). The comet passes through its other stationary point in late August -- when it will be at its farthest south point (declination -35.6 degrees) -- and thereafter begins heading towards the east-northeast.

Although presently seven weeks past perihelion, Comet NEAT is approaching Earth (minimum distance 1.94 AU on July 1) and accordingly may brighten by perhaps half a magnitude between now and opposition. After that it will probably begin fading fairly rapidly and it should drop below the threshold of visual detectability before much longer.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 April 9.45 UT, m1 = 14.3, 0.4' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

676. COMET NEOWISE C/2020 F3 Perihelion: 2020 July 3.68, q = 0.295 AU

I commented in the previous entry that Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673), which had been showing signs of putting on a bright showing as it approached perihelion in late May 2020, is instead starting to disintegrate and thus will probably not be putting on much of a show at all. I also commented that there have been a couple of recently-discovered comets that are exhibiting the potential of possibly becoming bright, and thus alleviating some of the disappointment we're feeling about the apparent "fizzle" of Comet ATLAS.

This is one of those comets. It was first detected by the NEOWISE mission on March 27, 2020, and although it was very low in my southwestern evening sky I thought it might be worth a visual attempt, and made one on the evening of April 10 but didn't see anything convincing. Some reports of positive visual observations by observers in the southern hemisphere, as well as some CCD-based reports that suggested the comet was brightening rapidly, convinced me it was worth another attempt, and on the evening of April 15, despite the fact it was less than 10 degrees above my southwestern horizon, I successfully observed it as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude. The visual observation reports from the southern hemisphere observers at around that same time suggest a brightness perhaps a magnitude or so brighter, and considering the observing circumstances I was dealing with, it is likely that their reports are closer to "reality."

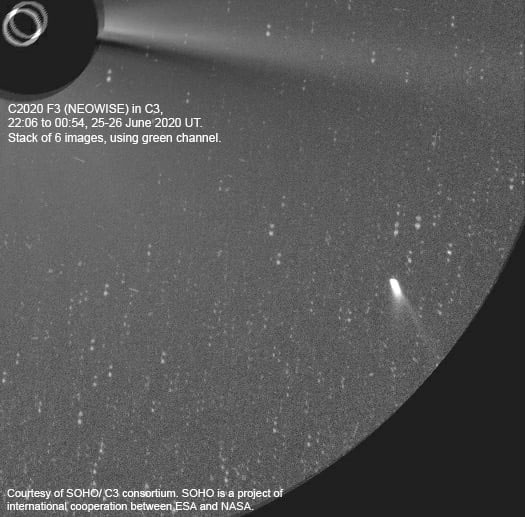

Comet NEOWISE is presently located in southwestern Canis Major near a declination of -33 degrees. It is traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 129 degrees) and is traveling almost due northward at slightly under one degree per day, however, due to its already-low location in my southwestern sky I will not be able to follow it for much longer. The observers in the southern hemisphere should be able to keep track of it until early June, when its elongation drops below 30 degrees; by that time it may have brightened to 10th magnitude or brighter. For a few days in late June it will be in the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO, although it will be on the far side of the sun from Earth at that time and thus may or may not be bright enough to be detectable in the images.

By the second week of July Comet NEOWISE becomes accessible in the northern hemisphere's morning sky, although at a fairly small elongation; it climbs rapidly northward, however, to reach a maximum northerly declination of +48 degrees on the 18th. At mid-month, meanwhile, it is in conjunction with the sun (25 degrees north of it) and thereafter primarily becomes an evening-sky object. Its elongation increases thereafter, although it also begins traveling towards the southeast fairly rapidly, reaching a maximum rate of almost four degrees per day around the time of its closest approach to Earth (0.69 AU) on July 23. Afterwards the comet continues heading southeastward and remains in the evening sky as it recedes from the sun and Earth, reaching a maximum elongation of 61 degrees in mid-August and finally disappearing into twilight by about mid-October.

Just how good a show we get from Comet NEOWISE depends, certainly, upon how it brightens as it approaches perihelion. With its relatively small perihelion distance it is entirely conceivable that it might start to disintegrate, as Comet ATLAS is presently doing, however it is also entirely conceivable that it might brighten dramatically as it approaches and passes through perihelion. If it has a substantial dust content it could develop a distinct dust tail, which with most comets is better developed after perihelion; since the comet will be appearing at a moderately high phase angle near 110 degrees during and just after mid-July there could be some enhancement of its brightness -- and the brightness of its dust tail -- due to forward scattering of sunlight. Since the comet was discovered by infrared-sensitive detectors that are designed to pick up, among other things, dust in comets, that, conceivably, could be a good sign concerning its dust content. As always, though, we will have to wait and see what the comet reveals to us as it makes its passage through the inner solar system.

I note, incidentally, that the date of Comet NEOWISE's closest approach to Earth coincides with the 25th anniversary of my discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp. The comet will be located in southern Ursa Major, and will be some 20 degrees above my northwestern horizon at the end of astronomical twilight; the moon will be just a couple of days past its "new" phase and thus won't interfere. If Comet NEOWISE brightens well as it approaches and passes through perihelion, and if it has a substantial dust content and develops a distinctive dust tail, then, conceivably, I could have a rather spectacular cometary sight to mark this important anniversary of one of the biggest events of my life. We'll see . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 April 16.12 UT, m1 = 13.3 (extinction corrected), 1.5' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (June 28, 2020): Comet NEOWISE remained accessible from the southern hemisphere up through early June. According to reports from observers in the southern hemisphere, it had brightened to almost 7th magnitude by the time it disappeared into evening twilight.

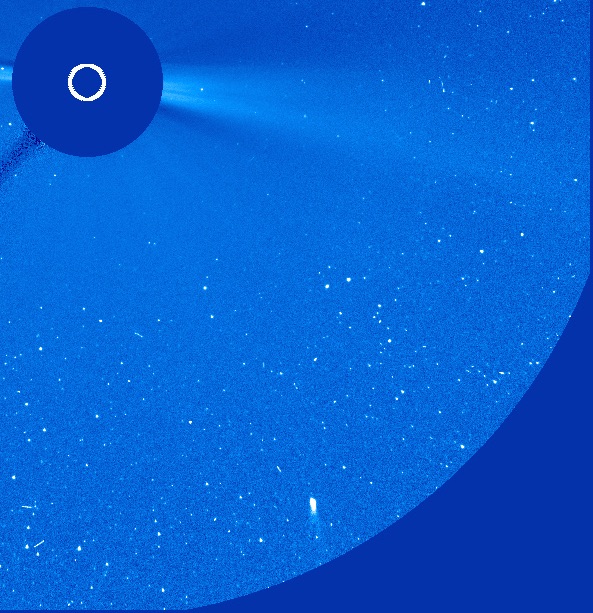

For the past few days Comet NEOWISE has been traversing the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO. When it first entered the field on June 22 it was close to 4th magnitude, and by the time it exited the field earlier today it had brightened to at least 3rd, perhaps close to 2nd, magnitude, and was exhibiting both an ion tail and a distinct (albeit foreshortened) dust tail. At face value, this would seem to suggest that it could be relatively bright when it becomes visible in the northern hemisphere's morning sky in early July, although it will remain close to the horizon in twilight and furthermore will have to compete with bright moonlight (full moon being on July 5). Depending upon how the comet behaves as it recedes from perihelion, it could still be a decent sight when it becomes more easily accessible in the northern hemisphere's evening sky after mid-July.

Comet NEOWISE as it appeared in the southwestern quadrant of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO. Left: June 23, 2020, at 20:42 UT. Right: composite image, prepared by Michael Jaeger in Austria, of six images from June 25 and 26, 2020. Both images courtesy NASA/ ESA.

Comet NEOWISE as it appeared in the southwestern quadrant of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO. Left: June 23, 2020, at 20:42 UT. Right: composite image, prepared by Michael Jaeger in Austria, of six images from June 25 and 26, 2020. Both images courtesy NASA/ ESA.

UPDATE (July 3, 2020): Comet NEOWISE passes through perihelion today. Just within the past couple of days it has emerged into the northern hemisphere's morning sky, very low and deep in twilight, and quite bright. I successfully observed it this morning, when its elongation was a mere 13.5 degrees; despite the low altitude and bright twilight I could easily detect it in 10x50 binoculars, with a bright and condensed coma and a hint of tail perhaps 15 arcminutes long. Telescopically its appearance is reminiscent of that of Comet McNaught C/2006 P1 (no. 395) when I viewed it during daylight. The overall brightness is difficult to measure precisely, as the only suitable comparison object around is the star Beta Tauri (visual magnitude 1.65), which is several degrees higher and thus less affected by atmospheric extinction. The reported measurement below should accordingly be considered as very approximate.

The comet's present brightness and appearance provides hopeful encouragement for a decent display later this month. Over the next several mornings it climbs higher into the morning sky (although moonlight will interfere some), but after conjunction with the sun (24 degrees north of it) on July 14 it becomes primarily an evening sky object, and then becomes relatively well placed for observation. It also moves from its present location beyond the sun to a location more between Earth and the sun, thus presenting a moderately high phase angle and consequently a potential for a brightness enhancement (especially of the dust tail) due to forward scattering of sunlight. Perhaps I really will have a good comet to help mark the 25th anniversary of the Hale-Bopp discovery!

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 July 3.46 UT, m1 = 0.6: (extinction corrected; twilight), 1'-2' coma, DC = 8 (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (July 18, 2020): After putting on a good show low in the northeastern morning sky, Comet NEOWISE has now gone through conjunction with the sun and is currently visible in the northwestern sky after dusk. While it has faded slightly as it has receded from perihelion, its dust tail has become longer and more prominent, and this, combined with the comet's overall better placement in the sky, has made it a prominent -- and beautiful -- naked-eye object. I now consider it as being a borderline "Great Comet" and rank it as the 5th-best comet I have seen in all my years of comet observing.

Recent photographs I have taken of Comet NEOWISE. Left: Morning sky, July 11, 2020. Right: Evening sky, July 16, 2020.

Recent photographs I have taken of Comet NEOWISE. Left: Morning sky, July 11, 2020. Right: Evening sky, July 16, 2020.

The comet is still a few days away from its closest approach to Earth which, as I've indicated above, coincides with the 25th anniversary of my discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp. Although the summer monsoon season in these parts always makes observation probabilities a bit problematical this time of year, I am cautiously optimistic that I will be able to mark the occasion by observing what I consider to be the best comet I have seen since that particular object was around. Afterwards, I expect Comet NEOWISE to fade steadily as it recedes from the sun and Earth, although it may very well remain somewhat bright for a few more weeks.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 July 17.15 UT, m1 = 2.6, tail 9 degrees long (naked eye)

677. COMET 210P/CHRISTENSEN Perihelion: 2020 April 7.92, q = 0.528 AU

One of the relatively recently-discovered small periodic comets of the inner solar system stops by for another visit. This one was discovered in May 2003 by Eric Christensen during the course of the then-recently inaugurated Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona, and I successfully observed it then as a very faint object (no. 335) and then again at the subsequent return in 2008-09 (no. 446), during the course of "Countdown." I discuss the history of those first two returns in its "Countdown" entry. Since then, it returned in 2014 (perihelion mid-August), but the geometry of that return was rather unfavorable; while it was recovered and in fact apparently reached 12th magnitude in CCD images taken at the time, it remained at a small elongation (especially for the northern hemisphere) and I did not look for it.

The current return is essentially identical to the discovery return of 2003, the corresponding times of perihelion passage being less than two hours apart. The comet approached perihelion from behind the sun and was not observable, and was not recovered until April 11, 2020 -- four days after perihelion passage -- when it was picked up by German amateur astronomer Roland Fichtl at an elongation of only 23 degrees; he reported it as being 12th magnitude. It has climbed higher into the evening sky on each successive night, although my initial attempts were delayed due not only to my having a poor horizon in that direction but I have also had to contend with clouds appearing at inopportune times. Finally, I had good conditions on the evening of April 23 -- by which time the comet's elongation had increased to 33 degrees -- and through a gap in the trees to my west I successfully observed it as a small and moderately condensed object of 12th magnitude; despite the fact I had a somewhat brightened background sky due to lingering twilight and zodiacal light it was not a difficult object to see.

Comet Christensen is currently located in north-central Taurus some 10 degrees east of the Pleaides star cluster (M45) and a similar distance north of the Hyades star cluster. It is traveling towards the east-northeast at somewhat under two degrees per day, and accordingly it continues to climb higher into the evening sky, although with the moon now also starting to emerge into the evening sky I will probably not obtain any more observations during this dark run. The comet is closest to Earth (1.08 AU) on May 7, and will be at an elongation of 50 degrees and traveling through northern Gemini a few days later after the full moon has left the evening sky; it may still be visually detectable then, although probably no brighter and 13th or 14th magnitude, and at best I will probably obtain only a couple of additional observations of it before it fades beyond visual range.

As I indicated in its "Countdown" entry, Comet Christensen's next return, in 2025 (perihelion late November), is relatively favorable. It is closest to Earth (0.43 AU) two weeks before perihelion passage and a week later is in inferior conjunction with the sun; by the time of perihelion passage it begins emerging into the morning sky, and although the elongation never gets very high it should nevertheless be accessible from the northern hemisphere without much difficulty. However, as I have indicated elsewhere in these pages, I am not at all certain that the health issues I have been dealing with for the past couple of years will allow me to still be observing comets at that time. It is thus entirely possible that whatever additional observations I am able to obtain of this somewhat unusual comet this time around will be my last. Or, perhaps not . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 April 24.12 UT, m1 = 12.1, 1.2' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

678. COMET 88P/HOWELL Perihelion: 2020 September 26.60, q = 1.353 AU

The evening-sky half of the April 2020 dark run was a busy time for comet observing and, although there were periods when clouds came through at inopportune times, for the most part the weather here in southern New Mexico was generally cooperative. The apparent disintegration of Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673) has been the biggest item, but there have also been two other comets that are both bright enough to detect with 10x50 binoculars that have attracted my attention. In addition, during that two-week period I added each of the above three comets to my tally and began incorporating them into my observational program.

As things turned out, as the moon began emerging into the evening sky following its "new moon" phase on April 22 I would add yet one more comet to my tally. This one is an old friend, and I discuss its overall history and my own history with it in its "Countdown" entry for its 2009 return (no. 457). Since that time I observed it again during its return in 2015 (no. 566), when it passed through perihelion in early April; it remained low in my southeastern morning sky throughout much of that return but I nevertheless followed it for 6 1/2 months and it reached a peak brightness near magnitude 9 1/2.

The present return thus becomes the 6th return at which I have observed Comet Howell. It was recovered as long ago as February 4, 2019, by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii, and independently four days later by the Mount Lemmon survey in Arizona. I had every expectation of observing the comet this year, but hadn't planned on looking for it this early; however, various reports I've read and images I've seen, including some Las Cumbres Observatory images that I took, suggested that it was worth looking for now, and on the evening of April 26 I successfully observed it as a small and relatively condensed object of 14th magnitude.

The geometry of the current return is rather similar to, indeed, slightly better than, that of 2009. The comet already went through opposition in early April and thus remains conveniently positioned in the evening sky for the next several months. At present it is located in central Virgo approximately four degrees east of the prominent double-star Gamma Virginis and, for the time being, is traveling almost due westward (passing 12 arcminutes north of that star on May 20); shortly thereafter, at the beginning of June, it passes through its stationary point and subsequently begins traveling towards the east-southeast. The comet remains in Virgo for the next several weeks, passing 1 1/2 degrees north of the bright star Spica shortly after mid-July, before crossing into Libra in mid-August and into Scorpius a month later, passing one degree north of the bright star Antares in late September before crossing into Ophiuchus in early October (and passing 15 arcminutes south of the globular star cluster M19 on October 5). Now traveling essentially due eastward, the comet spends the next month traversing the galactic center region, crossing into Sagittarius in mid-October and remaining in that constellation until the latter part of November when it crosses into Capricornus.

I expect Comet Howell to brighten slowly and steadily over the coming weeks. Around the time of its perihelion passage in 2009 it reached almost 9th magnitude and I could faintly detect it with 10x50 binoculars on a couple of occasions, and it would seem reasonable to suspect that it will do something similar this time around. I should be able to follow it until sometime around the end of the year.

As is true for several other of my "old friend" periodic comets, I will probably be observing Comet Howell at future returns for as long as I continue observing comets, although it is entirely possible that I could be concluding that activity within the not-too-distant future and thus this could be the final return during which I will observe it. The geometry at the next return, in 2026 (perihelion mid-March) is rather mediocre, especially for the northern hemisphere, although it is possible that I might be able to access it low in my morning sky some three months after perihelion passage. Meanwhile, the geometry at the following return, in 2031 (perihelion early September) is quite favorable; as I point out in the comet's "Countdown" entry, it will be making a fairly close approach to Mars during that return. We'll see what the future holds . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 April 27.14 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.6' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

679. COMET PRUYNE C/2020 H2 Perihelion: 2020 April 27.59, q = 0.834 AU

The evening-sky half of the April 2020 dark run is now over, but there's still the morning-sky half . . . and yet another addition to my lifetime comet tally, making a total of five for the month of April. The comet in question was discovered on April 26, 2020, by Theodore Pruyne during the course of the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona -- his second overall comet discovery -- and although it was reported as being 16th magnitude, some images I saw of it suggested it might be worth attempting visually, and on the morning of April 28 I successfully picked it up as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude. At the time it was traveling almost due northward at over 2 1/2 degrees per day and I could easily detect its motion over a period of 10 minutes.

Having just passed through perihelion, Comet Pruyne is traveling in a fairly steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 125 degrees) and will be closest to Earth (0.66 AU) on May 8. It is presently located in north-central Pegasus some five degrees west of the star Beta Pegasi (the northwestern corner of the "Great Square" of Pegasus) and is continuing to travel almost due northward quite rapidly, currently at three degrees per day and increasing to 3 1/2 degrees per day at the time of its closest approach to Earth. Over the next three weeks it travels through Lacerta, Andromeda, Cassiopeia, and Cepheus, entering northern circumpolar skies during the second week of May and reaching a peak northerly declination of +80.6 degrees on May 21. At that time the comet is in conjunction with the sun (60 degrees north of it) and technically becomes an evening-sky object afterwards; it then turns towards the south-southeast and travels through Camelopardalis and Ursa Major.

Although predicting the future brightness of a newly-discovered comet is always somewhat of a problematical process, a "best guess" scenario suggests that Comet Pruyne may brighten by a few tenths of a magnitude by the time it is nearest Earth, but will likely fade quite rapidly afterwards. It thus seems rather probable that I will only obtain, at best, a handful of additional observations of it before it fades beyond visual range.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 April 28.43 UT, m1 = 13.2, 1.4' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

680. COMET SWAN C/2020 F8 Perihelion: 2020 May 27.54, q = 0.430 AU

The past few years have been pretty lean when it comes to naked-eye comets. The most recent long-period comet to reach naked-eye visibility did so over four years ago, when Comet Catalina C/2013 US10 (no. 550) reached 6th magnitude in the northern hemisphere's morning sky during early 2016. Since then, Comet 252P/LINEAR (no. 592) reached between 4th and 5th magnitude as seen from the southern hemisphere in March 2016 (and was briefly between 5th and 6th magnitude when it became visible from the northern hemisphere the following month), and Comet 46P/Wirtanen (no. 653) reached 4th magnitude in late 2018, however both of these objects are Jupiter-family short-period comets that were making close approaches to Earth at the respective times, and never appeared as anything other than large "fuzzballs." We're due . . .

Indeed, for a while it looked like Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673) might become a respectably bright object, especially after its dramatic rise in brightness in early March, however in April it began to disintegrate and fade, and although at this writing in mid-May it is still visually detectable at 10th magnitude and apparently is continuing to undergo activity, its overall appearance is rather "ghostly" and it is now almost certain that there will be nothing of it left to see as it passes though perihelion at the end of this month. But just as this comet was starting to fade away, a new one arrived that somewhat took its place. This newer comet initially appeared in images taken with the Solar Wind ANisotropies (SWAN) ultraviolet telescope aboard the SOlar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft dating back to March 26, 2020, and were first noticed in early April by Australian amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo, who resides in Victoria. (Michael has been an experienced comet observer for many years and has discovered several previous comets in SWAN images; I had the pleasure of meeting him in person when I was visiting Australia early last year.) Ground-based observations soon showed that Michael's SWAN object was a 9th-magnitude comet in the southern hemisphere's morning sky.

Comet SWAN is traveling in a steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 111 degrees). Following its discovery it traveled northward and brightened rapidly, with observers in the southern hemisphere reporting it as being as bright as 6th magnitude in late April. By the beginning of May various southern hemisphere observers were reporting naked-eye sightings and a brightness near 5th magnitude, and meanwhile images were showing a long and somewhat complex ion tail several degrees long. Unfortunately, the comet seems to have begun fading from that point, with reported brightness measurements being back near 6th magnitude by the second week of May -- suggesting that it may have been undergoing an outburst during its period of rapid brightening.

LEFT: Comet SWAN as it appeared in an image taken by the SWAN ultraviolet telescope on April 28, 2020. Courtesy NASA/ESA. RIGHT: Wide-field image of Comet SWAN taken by its discoverer, Michael Mattiazzo, on May 4, 2020.

LEFT: Comet SWAN as it appeared in an image taken by the SWAN ultraviolet telescope on April 28, 2020. Courtesy NASA/ESA. RIGHT: Wide-field image of Comet SWAN taken by its discoverer, Michael Mattiazzo, on May 4, 2020.

Meanwhile, all those of us in the northern hemisphere could do was bide our time and wait for the comet to become accessible in our sky. By the time it did so, during the second week of May, not only had it begun fading, but the elongation from the sun had become quite small, and we also had to contend with bright moonlight (full moon having taken place on May 7). From my residential observing site I do not have a clear eastern horizon, but from a nearby site on the morning of May 12 -- by which time the comet's elongation had dropped to 27 degrees, and furthermore it was still slightly south of the sun -- while having to contend with a distant bank of low-lying clouds, in the twilight and bright moonlight I successfully spotted it in a 10-cm telescope, although I could do little more than tell it was "there." Four mornings later, under better sky conditions and with moonlight being much less of a factor (although by this time the comet's elongation had shrunk still further to 22 degrees), I was able to detect it in 10x50 binoculars as an object of 6th magnitude. (Ever the good sport, my partner Vickie dragged herself out of bed and accompanied me on both occasions.)

At this time, I honestly do not know how many more observations I might be able to obtain of Comet SWAN. There remains the uncertainty as to how its brightness will evolve over the next few weeks. Then, there is the matter of its relatively poor viewing geometry; the comet was already nearest Earth (0.56 AU) on May 12, and while its elongation will now start to increase, its rapid motion towards the northeast will put it in conjunction with the sun -- 25 degrees north of it -- right around the time of perihelion, at which time it will also be near its maximum northerly declination of +46.5 degrees. Thereafter it becomes an evening-sky object, although the already-low elongation will start to decrease again; meanwhile, on June 2 it passes one degree southwest of the bright star Capella, although unfortunately there will be a waxing gibbous moon in the evening sky at that time. The elongation drops below 20 degrees on June 9 and remains there until late July, by which time the comet will likely have become a faint object well beyond the range of visual observations.

So, while observers in the southern hemisphere did finally have a naked-eye comet -- albeit a relatively faint one -- unless Comet SWAN undergoes a dramatic outburst in the near future we northerners are essentially going to miss out. I'm still hoping that Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 (no. 676) might be able to come through for us, and based upon its recent behavior it's even possible that Comet Lemmon C/2019 U6 (no. 674) might cross the naked-eye threshhold late next month -- but all we can do now is wait and see.

SECOND OBSERVATION: 2020 May 16.44 UT, m1 = 6.3, 8' coma, DC = 4 (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (May 30, 2020): Following my initial observations of Comet SWAN it continued traveling northward and approached conjunction with the sun, in the process becoming less and less accessible for me (especially since I have a hill in that direction), but becoming somewhat more accessible for observers at more northerly latitudes. Unfortunately, it also began fading and clearly started to disintegrate, becoming more and more an elongated patch of light with little in the way of a central condensation. After perihelion and conjunction with the sun it started to become somewhat accessible in my evening sky, albeit at a very low altitude; due in part to weather I wasn't able to attempt an observation until the evening of May 29, by which time the evening sky was being brightened by a first-quarter moon. I did succeed in seeing the comet that night, but it was little more than a vague ill-defined "presence" somewhere between 7th and 8th magnitude; only 5 degrees above the horizon, it was a difficult object in the moon- and twilight-brightened sky.

At this time I have no expectations of seeing Comet SWAN again. The process of disintegration will almost certainly continue, and the elongation -- already at a small 25 degrees -- will shrink as the comet disappears into twilight over the next couple of weeks. Furthermore, the approaching full moon makes any observation attempts over the next week impractical, and by the time I have a dark evening sky again the comet will be gone.

So, for the second time in as many months a potential bright comet for the northern hemisphere disintegrates as it approaches perihelion. Hopefully, Comet Lemmon C/2019 U6 (no. 674) and/or -- especially -- Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F6 (no. 676), which are currently at 7th and 8th magnitude, respectively, according to observers in the southern hemisphere, will come through for us and give us something bright and worthwhile to observe.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 May 30.14 UT, m1 = 7.5:, 6' "coma," DC = 1 (20 cm reflector, 47x)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center