TALLY ENTRIES 681-690

As we begin to approach the mid-way point of 2020 in this coronavirus-changed world, life continues on. I remain busy with "Ice and Stone 2020," and an article I wrote for Sky and Telescope about the 25th anniversary of my discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp has just come out in print. My younger son Tyler just earned his Bachelor's Degree in Electrical Engineering from New Mexico State University, although there was no formal graduation ceremony (and, in truth, he hadn't planned on attending anyway). For the time being my older son Zachary remains in Adelaide, South Australia, where his partner Karina is finishing up her Doctoral degree at Flinders University. Meanwhile, due to coronavirus concerns Vickie's father has now been living with us for over two months, and it is conceivable that that could become a permanent arrangement, although no decisions have been made as of yet.

We have had a decent amount of clear weather lately, and I've been busy with comet observations, especially with the heavy pace of recent additions to my tally. Unfortunately, at least some of the hoped-for bright comet prospects have not panned out; Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673), which should have been reaching its brightest right about now, has all but completely disintegrated, and Comet SWAN C/2020 F8 (no. 680), which I've been able to observe in morning twilight a couple of times but which remains poorly placed for observations from my latitude, also appears to be fading and diffusing out, and whether or not there will be anything of it left to see when it becomes somewhat accessible in my evening sky this coming week remains to be seen. Two additional comets that at present are only accessible from the southern hemisphere do show some promise: Comet Lemmon C/2019 U6 (no. 674) has brightened rapidly within the recent past and theoretically could be close to naked-eye brightness when it becomes accessible for me again near the end of June, and Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 (no. 676) also appears to be brightening steadily. I still have hopes that Comet NEOWISE will put on some kind of decent display during July to help me mark the anniversary of the Hale-Bopp discovery, but we'll have to wait and see what happens.

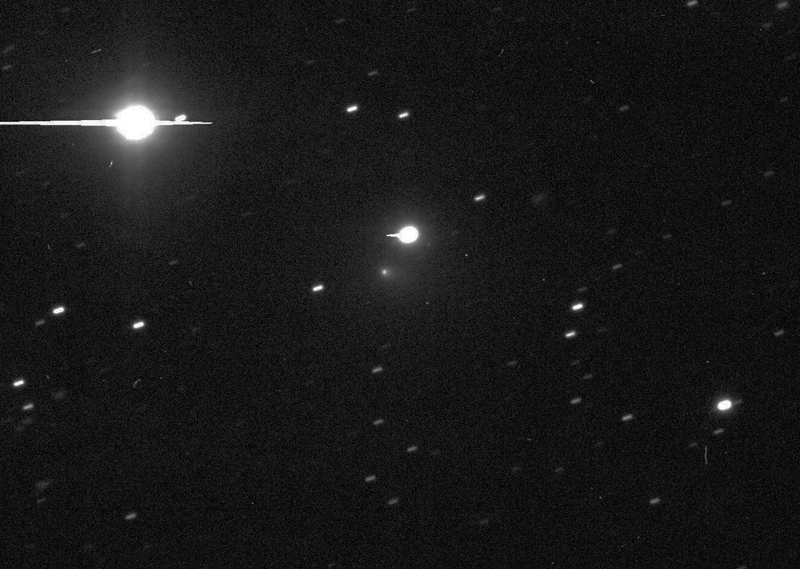

In the meantime, I've added one more comet to my tally. This object was discovered back on July 5, 2019, by the ATLAS program in Hawaii, at which time it was located in far northern circumpolar skies at a declination of +82 degrees and about 18th magnitude. It has remained in far northern skies ever since, traveling south to a declination of +60 degrees in early January 2020 before climbing back north to just north of declination +80 degrees in late April shortly after it had gone through opposition. Various reports I've read have indicated that it has been steadily brightening, and I made a couple of earlier unsuccessful attempts for it, however after taking a couple of recent images with the Las Cumbres Observatory network that indicated that it was close to being bright enough for visual observations I made an additional attempt under excellent sky conditions on the evening of May 21, and successfully spotted it as an extremely faint, small and condensed object of magnitude 14 1/2 near the limit of visibility, that exhibited the expected motion over the course of the next hour.

Comet ATLAS is traveling in a steeply-inclined orbit (inclination 82 degrees) and at this time is still a little over six months away from perihelion passage. For the time being it is still in northern circumpolar skies, in Draco at a declination of +75 degrees, and is traveling at half a degree per day, presently towards the south-southwest but turning more and more directly southward. After passing ten arcminutes northwest of the large galaxy NGC 4236 in early June and later crossing into Ursa Major, it travels through the eastern portion of the "bowl" of the Big Dipper late that month before crossing into Canes Venatici in late July and into Coma Berenices in mid-August; during the last week of that month it crosses the Coma Star Cluster (Melotte 111). By that time the comet will be getting low in the western sky after dusk and meanwhile may have brightened to about 13th magnitude.

After being in conjunction with the sun shortly before mid-October Comet ATLAS begins emerging into the morning sky around the time of perihelion passage in early December, at which time it will be located in southeastern Virgo and may have brightened to about 11th magnitude. Now traveling towards the south-southeast at somewhat over 40 arcminutes per day, it passes through eastern Hydra before crossing into Centaurus in mid-December and into Lupus at the beginning of January 2021; during the latter part of that month it enters southern circumpolar skies. The comet is nearest Earth (1.91 AU) in early February, at which time it will be located in Apus at a declination of -74 degrees; at the end of that month it passes just over 1 1/2 degrees from the South Celestial Pole. It travels back northward after that but remains in southern skies, and should remain visually detectable until perhaps April or May.

It does not appear, then, that I will be getting that many observations of this particular Comet ATLAS. When visible late this year it will be low in my southeastern morning sky, and it will probably only be accessible for a month of so -- perhaps six weeks -- before it drops below my southern horizon and I lose it. Given the uncertainty of all the goings-on right now, it will be interesting to see what the world, and my personal, circumstances are at that time.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 May 22.21 UT, m1 = 14.5, 0.3' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (November 28, 2020): Following its conjunction with the sun last month, Comet ATLAS has now started emerging into my morning sky, although for the time being it remains very low in the southeast just before and during dawn. I successfully picked it up three mornings ago as a difficult object of 12th magnitude when its elongation was slightly less than 32 degrees.

At present the comet is located in southern Virgo some 11 degrees southeast of the bright star Spica and is traveling towards the south-southeast at approximately 40 arcminutes per day. I hope to obtain another couple of observations after mid-December once the moon has cleared from the morning sky, at which time it may be marginally brighter, however its declination drops south of -30 degrees on December 14 and south of -40 degrees two weeks later, thus it remains at a low altitude above my southeastern horizon before I lose it completely. As I indicated above, the comet should remain accessible for visual observations from the southern hemisphere through the first few months of 2021.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 November 25.51 UT, m1 = 12.3:, 0.5' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

682. COMET 58P/JACKSON-NEUJMIN Perihelion: 2020 May 27.44, q = 1.377 AU

As I write these words shortly after mid-July 2020 I am quickly approaching the 25th anniversary of my discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1 (no. 199) which, probably not surprisingly, turned out to be a major life-changing event for me. Among many, many other things, the discovery and the comet's appearance as a "Great Comet" a year and a half later made it possible for me to have a career, of sorts, and while life has certainly settled down for me during recent years, I have the satisfaction of knowing that I will have that object, and all that it has made possible, as my legacy.

And, as fate would have it, there is a relatively bright comet in the sky right now to help me mark the occasion: Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 (no. 676), which has been an easy and spectacular naked-eye object and which is the best comet I have seen since the one that bears my name. By a most interesting coincidence, it is closest to Earth (0.69 AU) on the very anniversary of the Hale-Bopp discovery (July 23). Meanwhile, the annual summer monsoon season, which was somewhat slow in starting this year but which seems to have picked up within the past few days, has made observing Comet NEOWISE a less frequent event than I might want, but I have still managed to obtain a few good observations and photographs (a couple of which I have posted in an update to that object's tally entry).

Although Comet NEOWISE has been gathering most of the attention right now, there are still other comets out there, including this new addition to my tally -- a comet which I never had any expectation of observing this year. It is a periodic object, originally discovered in September 1936 independently by Cyril Jackson at the (now closed) Union Observatory in South Africa and Grigory Neujmin at Simeis Observatory in Crimea in the then-Soviet Union. (Both of these individuals discovered other comets as well, including periodic comets that I have also observed.) The comet turned out to have an orbital period of 8.6 years (currently, 8.25 years), but due to unfavorable viewing geometry and uncertain calculations it was missed at the subsequent returns in 1945, 1953, and 1962 before being successfully recovered during the relatively favorable return in 1970. It was subsequently recovered during its returns in 1978, 1987, and 1995.

The 1995 return was a distinctly favorable one, and I was able to follow the comet visually for four months (no. 203); my first observation came less than two months after my discovery of Comet Hale-Bopp, and there were several nights, including the night of my first observation, when I observed both comets. Comet Jackson-Neujmin peaked at an unexpectedly bright 10th magnitude during that return, although, curiously, this took place over a month past perihelion passage and two months past its closest approach to Earth. This led to some speculation that the comet might have been in the act of disintegration, which was strengthened when it remained unrecovered during its subsequent returns in 2004 and 2012 (although it's fair to note that both of those returns, especially the latter one, were geometrically unfavorable).

In 2020 the comet was predicted to pass perihelion in late May, again under somewhat unfavorable viewing geometry, and especially after its failure to appear during the previous two returns there was no real expectation that it would be recovered. However, in early April Chinese researcher Hua Su reported that he had detected an apparent comet in images back to March 26 taken by the Solar Wind ANisotropies (SWAN) ultraviolet telescope aboard SOHO, the positions and motion of which were consistent with that expected of Comet Jackson-Neujmin. Armed with this information, Australian amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo imaged, in bright moonlight, a 11th-magnitude comet on April 7 that was soon verified as indeed being that object, although it was located over one degree away from its expected location which in turn indicated that its predicted time of perihelion was over two days off. (Curiously, on those very same SWAN images Mattiazzo detected another comet, which turned out to be a new discovery (C/2020 F8), and which became dimly visible to the unaided eye from the southern hemisphere in late April and early May before briefly becoming visible from the northern hemisphere (no. 680) around mid-May as it was disintegrating. Even more curiously, the two comets passed perihelion on the same day -- P/Jackson-Neujmin preceding the other by a little over two hours -- although they are completely unrelated to each other.)

The fact that Comet Jackson-Neujmin was located so far away from its expected position, and furthermore was over six magnitudes brighter than expected, has further strengthened speculation that it may be going through its "death throes," and at the very least had been undergoing a major outburst that might quickly subside. However, the comet brightened to almost 10th magnitude around the time of perihelion passage, and although observation reports have been rather spotty, it seems to have faded only slowly and gradually since that time.

The comet was south of the sun at an elongation not much larger than 30 degrees at the time of its recovery, and thus observations were restricted to the southern hemisphere. This has remained the case ever since, with the elongation only increasing very gradually, and I suspected rather strongly that it would fade beyond the range of visual observations by the time it finally became accessible from my location around mid-July. However, the slow rate of fading has suggested that visual observations for me might indeed now be possible, especially after examining a set of images I took with the Las Cumbres Observatory network a few days ago (within which it appeared rather prominent), and during the past few mornings I have tried to make attempts for it. The monsoon conditions have made this a problematical and at times frustrating exercise, and on a couple of mornings I briefly observed faint suspects but was then clouded out before I could verify anything. Finally, on the morning of July 21 the clouds held off, and I successfully observed the comet as a small and moderately condensed object of magnitude 12 1/2. (While it is possible that I did in fact see the comet on one or both of the previous occasions, since I am unable to verify this one way or the other I do not consider these as being valid "observations.")

I am not at all certain how many additional observations I may be able to obtain of Comet Jackson-Neujmin this time around, or even if I will be able to observe it again. It remains south of the sun and with a present elongation of 50 degrees (being located five degrees southeast of the Hyades star cluster in Taurus) it is still very low in my eastern sky before dawn; since it is traveling due eastward at 40 arcminutes per day the elongation will continue to increase only gradually. Furthermore, since the comet is now almost two months past perihelion it will almost certainly continue fading, and with the current monsoon conditions I will likely not be able to attempt many more observations. At best, I will probably only see it another two or three times before it fades beyond visual range.

The next return of Comet Jackson-Neujmin, in 2028 (perihelion early September) is a very favorable one, with a minimum distance from Earth (0.49 AU) taking place later that month. If the comet maintains the same intrinsic brightness then that it has now, it could be a relatively bright object close to 8th magnitude. However, if as I suspect we are indeed now seeing the comet's "death throes," or at the very least a significant extended outburst, then it will likely be significantly fainter than that, or perhaps not even visible at all. Whether or not I am still actively observing comets at that time also remains to be seen, so it is distinctly possible that whatever observations of this comet I might be able to make over the next couple of weeks will be my last.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 July 21.44 UT, m1 = 12.5, 1.2' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

683. COMET 2P/ENCKE Perihelion: 2020 June 25.84, q = 0.337 AU

For the second time in a row, a comet that I had no expectation of seeing this year gets added to my tally. I discuss this famous comet in the "Countdown" entry for its 2007 return (no. 402) and also in its "Comet of the Week" presentation for "Ice and Stone 2020." After observing it during its favorable return in 2013 (no. 531), I followed it for two months during its rather mediocre return in 2017 (no. 610), however during its return this year its visibility was restricted to post-perihelion, which is usually the exclusive domain for observers in the southern hemisphere. Despite this, I nevertheless managed to pick it up on its way out before it faded from view. While I also observed it post-perihelion during its 1997 return (no. 231), that happened while I was visiting Australia (in significant part to view Comet Hale-Bopp C/1995 O1 (no. 199) after it had left the northern hemisphere's skies), and thus this is the first time that I have observed Comet Encke post-perihelion from the northern hemisphere. Overall, this is the 13th return at which I have observed Comet Encke.

As Comet Encke approached perihelion this year it did so from behind the sun (as seen from Earth), and thus was inobservable from the ground. It spent several weeks, meanwhile, within the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO, however it remained too faint for visibility; even when it exited the C3 field on June 18 -- at which time it should have been close to 7th magnitude -- it still was not visible. I was concerned that this might be a sign that the comet was close to disintegrating, however just before the end of June observers in the southern hemisphere began picking it up in evening twilight as a 7th-magnitude object. Historically, Comet Encke tends to diffuse out and fade fairly rapidly as it recedes from perihelion, and by the time moonlight began to interfere during the third week of July the southern hemisphere observers were reporting it to be around 9th magnitude, pretty much as expected. The comet was closest to Earth (0.62 AU) on July 30.

By the end of the first week of August, after the moon (which was full on August 3) had cleared from the evening sky, Comet Encke had started to become accessible from my location, very low in the southwest during late dusk, but due to its historical trend of rapid fading and diffusing out after perihelion I had no expectation of seeing it; indeed, on two previous returns that were similar to this year's I had attempted it under similar circumstances, unsuccessfully. However, I read a recent report from an observer in the southern hemisphere that indicated the comet was still visually detectable near magnitude 10 1/2, so after waiting through a couple of cloudy nights -- this being monsoon season here in New Mexico -- I was able to attempt it under somewhat mediocre sky conditions on the evening of August 7, and to my surprise I seemed to see a vague and diffuse object of 11th magnitude at the comet's expected position. Under somewhat better sky conditions the following evening I was clearly able to detect the comet -- thus confirming the previous night's suspect -- despite its being less than 10 degrees above the horizon and within the brightened background sky of late twilight.

At the time of my observations Comet Encke was located in eastern Hydra, about two degrees south of the star Gamma Hydrae. It is traveling towards the east-southeast, presently at two degrees per day but decreasing to slightly over one degree per day by the end of August; it crosses into northeastern Centaurus on August 19 and then into Lupus two days later before entering Scorpius on September 2. While it gradually becomes slightly higher in my evening sky over time, it is also continuing to fade and diffuse out, and especially with the monsoon conditions prevalent right now it is somewhat likely that I will not be observing it again. I'm not complaining, though; I'm quite glad to have gotten it this time around!

Comet Encke's next return (perihelion late October 2023) is much more favorable for the northern hemisphere; it will be conveniently accessible in the morning sky before perihelion and should reach at least 8th magnitude, possibly 7th. Provided that I am still observing comets then -- and, at this time, I plan to be -- I should be able to say "hello!" to this comet again, under distinctly better viewing circumstances than this year's. Hopefully the external world's circumstances will be better as well.

CONFIRMING OBSERVATION: 2020 August 9.13 UT, m1 = 10.9 (extinction corrected), 3' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

684. COMET CATALINA-ATLAS C/2020 K8 Perihelion: 2020 September 14.52, q = 0.475 AU

In this bizarre pandemic-laden summer of 2020, the comet activity has been relatively high, although the annual summer monsoon here in New Mexico has curtailed my observations quite a bit. Following its spectacular naked-eye display last month, Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 (no. 676) has now faded, although it remains a decent comet in binoculars, near 7th magnitude and still with a respectable (albeit faint) dust tail. A handful of other moderately bright comets have also inhabited the evening sky lately, although they, too, are fading, with the exception of Comet 88P/Howell (no. 678) which is presently around 10th magnitude and which may brighten by perhaps another magnitude by the time of its perihelion passage five weeks from now. The morning sky, meanwhile, has been relatively quiet, the only comet I've been observing lately being 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 (no. 498), which underwent one of its characteristic outbursts in late July and which is presently observable near 13th magnitude, although its coma has now grown rather large and diffuse.

Another comet has now joined the morning sky, although it is faint and it probably won't be around for very long. It was originally detected as an apparently asteroidal object by the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona on three separate mornings (May 25, 28, and 29, 2020) -- all under separate preliminary designations -- and then independently by the ATLAS program in Hawaii on June 7. Robert Weryk of the University of Hawaii then successfully linked all four reports as being the same object and, based upon its orbit, suggested it might be a comet; this was soon verified by other observers. At the time of its discovery the comet was a very faint object of 19th magnitude but it has brightened steadily since then; a couple of recent sets of images I've taken with the Las Cumbres Observatory network suggested it might be bright enough for visual observations, and I made an unsuccessful attempt on the morning of August 1. After the moon had cleared from the morning sky I tried again on August 18, and successfully detected it as a faint, vague, and diffuse object of 14th magnitude that traveled rapidly across the telescopic field of view during the half-hour that I followed it. At that time it was located in western Gemini crossing the supernova remnant IC 443.

Comet Catalina-ATLAS was closest to Earth (0.60 AU) on August 14 and at the time of my initial observation was racing towards the east-southeast at three degrees per day. It slows down somewhat over the next few weeks as it continues crossing southern Gemini (passing two degrees south of Venus on August 22) before crossing into Cancer late this month and into Hydra in early September (traversing the "head" of that constellation as it does so) and finally crossing into southern Leo shortly before the end of that month. Meanwhile, the elongation decreases fairly rapidly, to below 40 degrees by the last week of August and to below 30 degrees after the first week of September.

The comet's relatively small perihelion distance is potential cause for excitement, and ostensibly it might brighten by one or two magnitudes by the time it starts to disappear into morning twilight. However, it appears to be quite faint intrinsically, and it may very well start to disintegrate as it approaches perihelion -- although, thus far, it has not exhibited any signs of doing so. If it does start to disintegrate, it is at least conceivable that it might undergo a temporary surge in brightness, like that exhibited a couple of years ago by Comet PANSTARRS C/2017 S3 (no. 647) and earlier this year by Comet ATLAS C/2019 Y4 (no. 673). Meanwhile, if it does manage to survive perihelion passage it recedes from the inner solar system on the far side of the sun from Earth, and while it remains in the morning sky it also remains at a small elongation and in any event will almost certainly be too faint for visual observations.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 August 18.44 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.8' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

685. COMET ATLAS C/2020 M3 Perihelion: 2020 October 25.62, q = 1.268 AU

I have written often in previous tally entries of the summer monsoon that strikes New Mexico during the months of July and August, producing a significant fraction of our annual rainfall and, accordingly, a fairly large number of cloudy nights. Normally the monsoon starts to sputter somewhat during the latter part of August, although it usually continues on in some fashion well into September -- indeed, the most intense monsoon thunderstorm I have ever experienced occurred in mid-September seven years ago and led to significant flooding in my neighborhood. In terms of rainfall this year's monsoon has perhaps been a bit below average, although we still have had the usual cloudy nights. Furthermore, several major fires in California and Colorado have generated a large amount of smoke that has drifted over and remained over this area for well over a week now, with the result being that even when the nights have been "clear" the overall sky transparency has been mediocre at best. I accordingly have not had much opportunity to observe comets (or any other astronomical objects) within the recent past.

With the full moon coming up next week I wanted one more session with the comets in the morning sky, so despite the less-than-ideal sky conditions I spent the morning of August 26 looking for several comets, including a couple of comets I have been following -- in the process obtaining what will quite likely be my last observation of the previous comet -- as well as three comets that I have not seen (or, at least, have not seen yet). One of these three comets was this object, which had been discovered on June 27, 2020 by the ATLAS program in Hawaii. At that time it was a very dim object of 19th magnitude, but I expected it to become bright enough for visual observations around the time of its perihelion passage, and indeed I had expected to begin making attempts for it next month. A recent report suggested, however, that it might already be bright enough for such attempts, but when I looked for it I couldn't see anything convincing. The mediocre sky conditions, the fact that the comet was quite deep in my southern sky (at a declination of -36 degrees), and was also close to some bright field stars, all probably contributed to my failure to see it, for a couple of images I took with the Las Cumbres Observatory network shortly thereafter indicated that it might very well be within visual range. On the following morning the comet was in a better star field, and moreover the sky conditions were somewhat better than they had been the previous morning, and I successfully detected it as a very faint and slightly condensed object a little fainter than magnitude 13 1/2. Since that time I have read very recent reports from and seen images taken by observers in the southern hemisphere -- where the comet is much higher in the sky -- that suggest the comet may now be even brighter, perhaps close to 11th magnitude.

At present Comet ATLAS is located in the southern

remains in Auriga for the next few months. Based upon the brightness I observed it might peak near 10th or 11th magnitude around the time of perihelion passage and its closest approach to Earth, and if one takes the recent reports from the southern hemisphere at face value, these would suggest the comet might even become as bright as 8th magnitude. In any event, it should remain visually detectable through the first one to two months of 2021 as it recedes from the sun and Earth.

Comet ATLAS turns out to be a Halley-type object, with the most recent calculations indicating an approximate orbital period of 139 years. This suggests that the previous perihelion passage might have taken place sometime during the early 1880s, and perhaps depending upon what time of year perihelion occurred it might have been detectable by the comet hunters of that era. As it is, there do not seem to be any comets from that time frame that appear to be good candidates for the previous return of Comet ATLAS; the closest match in terms of orbital elements is Comet Dodwell-Forbes 1932n, which reached a peak brightness near 8th magnitude around the time of its perihelion passage at the very end of 1932. In addition to the discrepancy in orbital period -- and, indeed, calculations indicate that Comet Dodwell-Forbes' orbital period is about 262 years -- while some of its orbital elements are quite similar to those of Comet ATLAS, others are different enough to suggest that the similarities are likely nothing more than coincidental. Perhaps anyone who might be around to view Comet ATLAS around 2160 would be able to shed some further light on this issue . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 August 27.42 UT, m1 = 13.7, 0.8' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (September 16, 2020): Following my initial observation of Comet ATLAS, clouds and weather prevented any further observations up until the time moonlight washed out the morning sky, and then after waiting out the moon I had to contend with several nights of extremely hazy skies due to smoke from fires in California and elsewhere. I finally had some relatively decent sky conditions this morning, and could tell that the comet is indeed a relatively large and diffuse object of 11th magnitude, consistent with the reports from the observers in the southern hemisphere, along with various recent images I have seen. If the comet brightens "normally" from here on out it should reach perhaps 9th magnitude around the time it is closest to the sun and Earth a month and a half from now.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 September 16.45 UT, m1 = 10.8, 4' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

686. COMET 156P/RUSSELL-LINEAR Perihelion: 2020 November 17.87, q = 1.333 AU

A rather interesting and colorful story accompanies the discovery of this short-period comet. That story begins in September 1986 when Kenneth Russell, an astronomer based at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales, discovered the trailed image of an apparent faint comet on a photograph taken early that month as part of the regular patrol program at Siding Spring. Unfortunately, however, Russell and others were unable to locate a confirming image of this apparent comet on a photograph taken later that month, and the discovery was never announced.

In January 2001 Tim Spahr, based at the IAU's Minor Planet Center, noticed that two apparent asteroids discovered by the LINEAR program in New Mexico the previous year -- 2000 QD181, imaged on two nights in late August and early September, and 2000 XV43, imaged on several nights between early November 2000 and mid-January 2001 -- were in fact the same object, and furthermore noticed that this object was identical to the apparent asteroid 1993 WU that had been discovered by Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker during the course of their photographic survey program at Palomar Observatory in California and photographed on two nights in November 1993. Spahr determined that the object was traveling in a comet-like orbit (eccentricity 0.56) with a period of approximately 6.85 years and a perihelion distance of 1.60 AU, and then, in April 2003, found that it was identical to the probable comet that Russell had discovered in 1986. Now armed with the information on precisely where to look, the astronomers at Siding Spring were finally able to locate the comet on the second photograph, and meanwhile the comet's existence, along with its various discoveries, was formally announced under the name "Russell-LINEAR."

The comet returned to perihelion in 2007 and in 2014 and was duly recovered both times, but it remained an inactive object and was never brighter than about 19th magnitude. It subsequently passed 0.36 AU from Jupiter in March 2018, an encounter which shortened its orbital period to 6.44 years and decreased its perihelion distance to its current value of 1.33 AU. On the present return it was recovered on June 27, 2020 by the ATLAS program in Hawaii, and independently a day later by Japanese amateur astronomer Hidetaka Sato utilizing a remotely-controled telescope at Siding Spring.

As it happens, the viewing geometry at this year's return is excellent, with the comet's being at opposition around the time of the September Equinox and passing 0.48 AU from Earth on October 23. Even if it were to remain inactive like it has on its several preceding returns I thought there was a reasonable chance of detecting it visually, perhaps as a stellar object near 15th magnitude, however it is not unusual for comets being "kicked inward" by approaches to Jupiter to undergo enhanced brightening and outbursts -- a kind of being "shaken up" -- and if that were to happen with P/Russell-LINEAR it might well exhibit cometary activity and become even brighter.

This scenario appears precisely to be what has happened. On October 6 an amateur astronomer in Ukraine, Taras Prystavski, reported that in images he had taken remotely via one of the other telescopes at Siding Spring, Comet Russell-LINEAR was exhibiting a very bright condensed interior surrounded by a faint wispy outer coma, near an overall brightness of 13th magnitude. After seeing Prystavski's report I submitted a set of images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network, and the returned images (taken from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory) confirmed his report. That same evening, despite the comet's being low in my southeastern sky (at a declination of -31 degrees) and under less-than-ideal sky conditions (primarily due to lingering smoke from fires in the western U.S.) I successfully observed it visually as a faint and vague object with a distinct small central condensed region and a faint wispy coma -- consistent with its appearance on the CCD images. Four nights later (i.e., on the evening of October 10), under better sky conditions and with the comet's being somewhat higher in the sky, I observed it again, with its overall appearance being similar. On both occasions I measured a brightness between magnitudes 13 and 13 1/2.

At present Comet Russell-LINEAR is located in northwestern Sculptor approximately two degrees west of the star Delta Sculptoris and is traveling slightly westward of due north at a little over half a degree per day. It crosses into eastern Aquarius shortly after mid-October and passes through its stationary point a few days before the end of that month, then crosses into Pisces in mid-November, at which time it is near perihelion and traveling towards the north-northeast at 50 arcminutes per day. Afterwards it curves more and more towards the northeast and slows down, and remains in (or at least near) Pisces through the end of 2020.

Given the comet's sketchy observational history and the current observational circumstances, it is difficult to know what to expect in terms of its future brightness. If, as appears at least somewhat likely, its present brightness is the result of a recent outburst, the current coma may disperse over the next few weeks and its overall brightness may fade, but as I indicated earlier it may well remain visible as a near-stellar object at least through perihelion and for a while afterwards. In any event, I expect it to fade beyond visual range by sometime in December.

This will likely be the only return during which I will obtain observations of Comet Russell-LINEAR. It has relatively favorable returns in 2033 and in 2053, although perturbations will have increased its perihelion distance to slightly over 1.4 AU. Another approach to Jupiter will decrease its perihelion distance to a little over 1.2 AU by the latter part of the 21st Century, although I have no expectations of being around then to take advantage of this.

Here at home, Vickie and I remain safe, and relatively isolated, during the current coronavirus pandemic. Her father, who has been staying with us since mid-March, has now completely moved in with us, and will likely live with us indefinitely. My older son Zachary, who has been living in Australia since early 2016 (and who Vickie and I were able to visit when we where there in early 2019) is moving back to the U.S. later this month, and meanwhile his brother Tyler, who successfully earned his Bachelor's Degree in Electrical Engineering back in May but who has had trouble securing employment in the current economic climate, has had some rather promising developments on that front within the recent past. As I begin to approach the end of "Ice and Stone 2020" I am starting to give thought to how I want to proceed afterwards, and may soon start to explore some potential avenues. And finally, what is shaping up to be the most important U.S. Presidential Election in my lifetime is now just a little over three weeks away, and while I will refrain from commenting further in this space, I am cautiously hopeful of a positive outcome.

SECOND OBSERVATION: 2020 October 11.18 UT, m1 = 13.4, 0.7' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

687. COMET ERASMUS C/2020 S3 Perihelion: 2020 December 12.67, q = 0.399 AU

Ever since going on-line in 2015 the ATLAS program based on Hawaii has become a strong force in the search efforts for comets and near-Earth asteroids. While perhaps not quite as prolific as the Catalina/Mount Lemmon and Pan-STARRS programs, ATLAS has nevertheless made a significant number of discoveries, having as of now discovered over 500 near-Earth asteroids and over 50 comets; of the 53 ground-observed comets discovered (and announced) so far this year, 12 of them are ATLAS discoveries. ATLAS is also beginning to have a fairly significant impact on my comet tally: as of now I have observed 11 ATLAS-discovered comets, 7 of these having the name "ATLAS" (one of these being shared with the Catalina program) and four more having been named for astronomers associated with ATLAS who noticed a cometary appearance of the objects before reporting them. One of these comets, Comet ATLAS C/2020 M3 (no. 685), is currently the brightest comet in the nighttime sky, being a binocular-visible object of 8th magnitude.

This newest comet on my tally was discovered on September 17, 2020 by Nicolas Erasmus, an astronomer at the South African Astronomical Observatory who participates in examining images taken by the ATLAS survey; the discovery images were taken by ATLAS' telescope on Mauna Loa. The comet was a somewhat dim object of 17th or 18th magnitude at the time of its discovery, but appears to have brightened rapidly since then; after seeing images and reading reports that suggested it might be visually detectable, I made an attempt on the morning of October 15 -- the first morning after the moon had left the morning sky -- and easily saw it as a diffuse 12th-magnitude object that moved noticeably against the background stars over a span of 15 to 20 minutes.

Comet Erasmus is traveling in a rather shallowly-inclined direct orbit (inclination 20 degrees). At present it is near its maximum elongation of 64 degrees, being located in western Hydra approximately three degrees south of the star Theta Hydrae, and is traveling towards the east-southeast at slightly over one degree per day. Over the next few weeks it travels through the constellations of Sextans, Crater, Corvus, and (beginning in late November) southern Virgo; meanwhile, it is closest to Earth (1.05 AU) on November 19, at which time it will be traveling at slightly over two degrees per day. After that, the comet rapidly disappears into the dawn sky as it travels over to the far side of the sun from Earth, with the elongation dropping below 30 degrees at the end of November and below 20 degrees after the first week of December. Based upon its present brightness it might be close to 7th or 8th magnitude around that time.

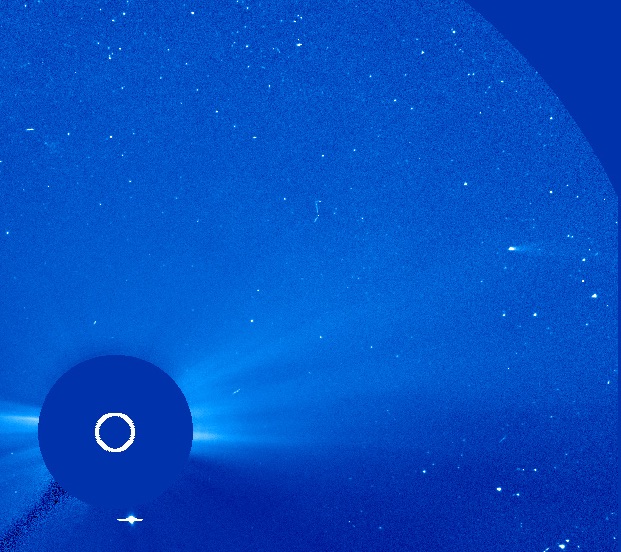

In late December and early January the comet spends two weeks traversing the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO, and possibly may be bright enough to detect in the LASCO images. Afterwards, the comet remains buried in sunlight for the next several months as it recedes from the inner solar system, indeed the elongation does not go above 30 degrees until early April 2021, by which time it will likely be very faint.

It is unfortunate that Comet Erasmus is not making its passage through the inner solar system, say, three to six months later. Had it done so, it would have come quite a bit closer to Earth -- 0.4 to 0.5 AU -- and become much better placed for observation, and perhaps might have become a naked-eye object of at least 5th of 6th magnitude. Such is the way things go, though . . .

In the meantime, I suspect that ATLAS will continue to have a non-trivial impact on my comet tally during the near-term foreseeable future. There are at least four inbound ATLAS-discovered comets that I have some reasonable expectation of observing -- one of which I've already attempted -- and of course it should certainly continue to discover more comets during the months and years to come. In early 2021 an additional ATLAS telescope is expected to be placed into operation at the South African Astronomical Observatory, and this should go quite a ways toward filling the hole left in the southern hemisphere survey efforts following the demise of the Siding Spring Survey in Australia seven years ago, and in the process produce even more comets for me to observe for however long I continue to remain active in this endeavor.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 October 15.45 UT, m1 = 11.8, 2.0' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (October 19, 2020): A revised orbital calculation for Comet Erasmus indicates a slightly smaller perihelion distance, and introduces only minor changes to the above viewing scenario. As the comet approaches perihelion, the elongation in the morning sky drops below 30 degrees during the last days of November and below 20 degrees during the first week of December; it traverses the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO during the last two weeks of December and exits the C3 field on January 2, 2021; and as the comet leaves the inner solar system its elongation does not rise above 30 degrees until mid-April 2021.

UPDATE (October 24, 2020): When I observed Comet Erasmus a couple of mornings ago it had brightened a full magnitude from my initial observation a week earlier. While I don't expect this rapid rate of brightening to be maintained through perihelion passage, my recent measurement does suggest that the comet may be somewhat brighter than the above scenario indicates, perhaps being between 6th and 7th magnitude when it disappears into the dawn around the beginning of December, and perhaps between 7th and 8th magnitude (and thus readily detectable) when it traverses the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO late that month.

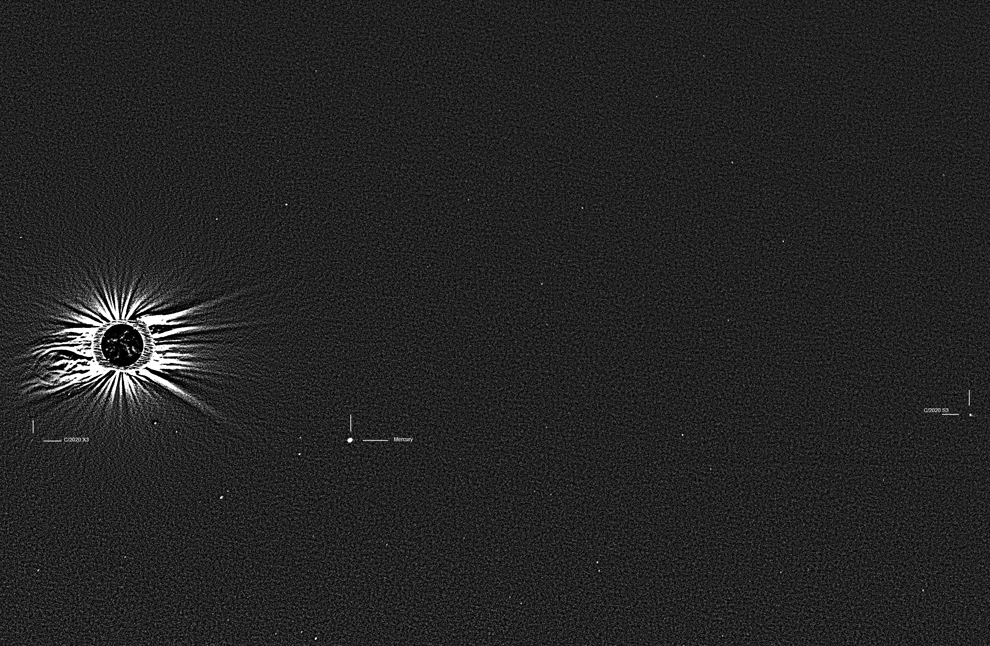

Comet Erasmus will be located 11 degrees west of the sun at the time of the total solar eclipse on December 14 (the path of which crosses central Chile and Argentina). My recent observation suggests the comet could be close to 6th magnitude at that time, and thus theoretically could be detectable, at least via imaging and possibly even visually, during totality.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2020 October 22.46 UT, m1 = 10.7, 3.2' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (December 20, 2020): By the time Comet Erasmus started disappearing into the dawn sky in late November it had brightened to 7th magnitude, and telescopically I could detect a westward-pointing ion tail up to 15 arcminutes long (which appears significantly longer on CCD images I have seen). A couple of observers who successfully followed the comet into the dawn in early December (and also in bright moonlight) reported it as being close to 6th magnitude at that time.

Comet Erasmus had brightened to 4th magnitude by the time of the total solar eclipse on December 14, although I am not aware of any visual sightings, and I am only aware of one successful recording of it on an image (shown below). Meanwhile, as expected the comet entered the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO on December 18, still close to 4th magnitude and sporting a westward-pointing tail over half a degree long. It should remain visible within the C3 field up until the beginning of January 2021, although since it is receding from both the sun and Earth it may fade during that time.

LEFT: A highly processed image of the sun taken during the total solar eclipse on December 14 by British astronomer Nick James from Neuquen, Argentina. Comet Erasmus is at the far right, Mercury is to the lower right of the sun, and the Kreutz sungrazer Comet SOHO C/2020 X3 is close to the sun on its lower left. Courtesy Nick James. RIGHT: Northwestern quadrant of the LASCO C3 image from SOHO taken at 19:54 UT on December 19. Mercury is just below the occulting disk blocking the sun. Courtesy NASA/ESA.

LEFT: A highly processed image of the sun taken during the total solar eclipse on December 14 by British astronomer Nick James from Neuquen, Argentina. Comet Erasmus is at the far right, Mercury is to the lower right of the sun, and the Kreutz sungrazer Comet SOHO C/2020 X3 is close to the sun on its lower left. Courtesy Nick James. RIGHT: Northwestern quadrant of the LASCO C3 image from SOHO taken at 19:54 UT on December 19. Mercury is just below the occulting disk blocking the sun. Courtesy NASA/ESA.

FINAL OBSERVATION: 2020 November 26.50 UT, m1 = 7.0, 5' coma, DC = 6 (10x50 binoculars); tail 15' in p.a. 250 degrees (20 cm reflector, 47x)

688. COMET 398P/BOATTINI P/2020 P2 Perihelion: 2020 December 26.74, q = 1.306 AU

I observed this comet during its discovery return in 2009 (no. 465), during which it reached a peak brightness near magnitude 13.5, and I discuss the details of its discovery and its basic orbital information in its "Countdown" entry. I concluded that entry by noting that it would be returning late this year under favorable circumstances, and stating that "If I'm still observing comets then -- and I probably will be, at least at some level -- I may very well be seeing this one again." Well, here I am 11 years later, and, yes, I'm still observing comets, and I am indeed observing this comet again. For what it's worth, this turns out to be my 200th "repeat" comet, i.e., my current tally comprises 488 separate comets, with the additional 200 -- including this one -- being observations made during subsequent returns of various periodic comets within that group of 488.

After being missed during its unfavorable return in 2015, Comet Boattini was recovered on August 11, 2020 by Nicolas Erasmus -- discoverer of the preceding comet on my tally -- during the course of the ATLAS survey; he initially reported it as a new comet discovery, but its identity with the expected Comet Boattini was soon established. It was a relatively dim object of 19th magnitude at the time but has brightened steadily since then, and when I made my first attempt for it on the evening of November 10 I successfully detected it as a small and faint object of 14th magnitude.

At present the comet is located in northern Eridanus, and traveling slowly in a generally eastward direction. Over the next few weeks it curves more northward, eventually traveling essentially towards the north-northeast before turning back towards more directly northeastward, and in the meantime it gradually picks up speed in its daily motion; it crosses into western Orion at the very beginning of January 2021, then traverses the "shield" of that constellation shortly thereafter, before crossing into eastern Taurus shortly before the end of that month. Meanwhile, the comet is at opposition in late November and is closest to Earth (0.38 AU) on December 22, just four days before perihelion passage. Around that time it should reach a peak brightness somewhere between 12th and 13th magnitude, and it should remain visually detectable until perhaps late January or early February 2021.

The past few weeks have been relatively eventful around here. After living in Australia for the past 4 1/2 years, my older son Zachary has just recently returned to the U.S., and although he is temporarily staying here in the area he plans to move to the Albuquerque area after the first of next year. My younger son Tyler, who successfully earned his Bachelor's Degree in Electrical Engineering from New Mexico State University back in May, just recently landed a job at White Sands Missile Range and plans to relocate to the western slopes of the Sacramento Mountains (on the other side of Cloudcroft) within the not-too-distant future. On a less-than-pleasant note I suffered an injury to my left leg a couple of weeks ago; it wasn't serious and I am gradually healing, although it has nevertheless slowed me down somewhat from my normal pace -- including in my observational activities, although I have tried to keep those up as much as I can. On the other hand, while I will refrain from commenting on it much here, I'll just say that I am relieved at the results of the recent Presidential election here in the U.S., but it is also clear to me that much work remains to be done in healing our society. Perhaps educational activities like "Ice and Stone 2020" (which is now nearing its end, but I am starting to give thought to what comes afterward) can make a contribution towards this effort, and I may express some thoughts about that in this space from time to time as I pursue whatever might come next.

With its current orbital period of close to 5.5 years, Comet Boattini's next return, in 2026 (perihelion early July) is unfavorable, but the return after that, in 2032 (perihelion early January) is another good one only slightly inferior to this year's. Hearkening back to my closing thoughts in the entry for the 2009 return, if I'm still observing comets 11 years from now it is conceivable that I'll be observing it again then. But, unlike my thoughts from 2009, I'm not at all sure that I'll still be actively observing in 2031-32; I've repeatedly discussed in this space potential plans for "retiring" from visual comet observing after 2024, although how solid those plans end up being remains to be determined. Still, events like my recent leg injury and its aftermath are bringing home to me the fact that my days of visual comet observing are numbered -- what kinds of numbers those turn out to be will be revealed on that proverbial bridge that I'll cross whenever I get to it.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 November 11.22 UT, m1 = 14.1, 0.6' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

689. COMET 11P/TEMPEL-SWIFT-LINEAR Perihelion: 2020 November 26.23, q = 1.389 AU

Ever since the IAU introduced the short-period comet number designations at the beginning of 1995, this has remained the lowest-numbered comet that I had not yet seen but had entertained some hopes of seeing at some time. (The two lower-numbered comets that I have not seen, 3D/Biela and 5D/Brorsen, both disintegrated during the mid- to late 19th Century, and thus there is no possibility of ever observing them.) I've had to wait a while for this one but have finally gotten it; as things turn out, this is the first time in over a hundred years that visual observations of this comet have been possible.

The comet's rather checkered history begins in November 1869 when one of the top comet hunters of the mid-19th Century, the French observer Wilhelm Tempel, discovered it from Marseille Observatory. It was followed for six weeks and although the astronomers of that era recognized it as a short-period comet, it wasn't well enough observed for an accurate orbit to be computed. After being missed at its subsequent return it was accidentally re-discovered by the champion American comet hunter Lewis Swift in October 1880, and shortly thereafter it was recognized as being identical to Tempel's comet from eleven years earlier, with a relatively short orbital period of 5.5 years. (The comet's intrinsic faintness is demonstrated by the fact that, despite its passing only 0.13 AU from Earth, it never became brighter than 8th magnitude.) It was observed again eleven years later and, due to a distant approach to Jupiter which increased its perihelion distance from 1.1 to 1.2 AU and slightly increased its orbital period, was missed at the next two returns before finally being recovered again in 1908. The viewing conditions were moderately favorable then and it was followed for three months, reaching a peak brightness of 12th magnitude.

Following its 1908 return Comet Tempel-Swift (as it was known at the time) underwent a series of approaches to Jupiter that increased its perihelion distance still further and also increased its orbital period to almost exactly 6 years, and that furthermore continuously brought it to perihelion when it was on the opposite side of the sun from Earth and thus unobservable. Although later approaches to Jupiter eventually moved it away from that configuration, by that time several decades had elapsed and the comet was essentially "lost." It was one of the comets examined by then-Yale University graduate student Brian Marsden in his 1963 study on "lost" periodic comets, and it appeared that the conditions for recovery might be favorable that year, but despite several searches nothing was found. (These searches did lead to the discovery of another short-period comet, 59P/Kearns-Kwee, that I successfully observed on its 1990 return (no. 148).) Additional unsuccessful searches at what were believed to be favorable returns in 1969 and 1982 essentially showed that the comet was hopelessly "lost," and -- if it actually still existed -- any future observations would have to be by accident.

That accident finally happened in December 2001, when the LINEAR program in New Mexico discovered a very faint comet (18th to 19th magnitude) that within a couple of days after the discovery was announced was recognized as being none other than the long-lost Comet P/Tempel-Swift. At that time its perihelion distance was 1.58 AU and its orbital period was 6.4 years. (As an incidental aside, of the 222 comets that LINEAR is credited with discovery by name, I have now visually observed 71 of them -- almost 1/3 -- and with the inclusion of multiple returns of periodic comets the name "LINEAR" now appears 74 times on my tally, almost 11% of the total.)

The comet -- now renamed P/Tempel-Swift-LINEAR -- was poorly placed at its 2008 return and was missed, but was recovered during its 2014 return, although it remained a very faint object of 19th to 20th magnitude. Afterwards, an approach to Jupiter (0.60 AU) in September 2018 shortened its orbital period to almost exactly 6.0 years and decreased its perihelion distance to its present 1.39 AU, and furthermore brought it to perihelion this year under favorable viewing circumstances, and at long last bringing the prospect of visual observations again.

The comet was recovered on July 25, 2020 by Jean-Francois Soulier via his 29PREMOTE Observatory in Dauban, France. It was about 20th magnitude at the time, but brightened quite slowly afterwards, and was still only about 18th magnitude in September. It seems to have brightened a bit more rapidly since then, and I began taking occasional images of it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network in mid-October, although it continued to remain fainter than I might have hoped. However, just within the past couple of weeks some experienced imagers, among them Michael Jaeger in Austria, began reporting a large and diffuse outer coma, and when I made my first visual attempt, on the evening of November 14, I was somewhat surprised to see a very faint, vague, diffuse and uncondensed object of 14th magnitude, that exhibited the expected motion over the course of an hour. It exhibited the same basic brightness and appearance when I observed it again three nights later.

At present Comet 11P is located in central Pisces, 2 1/2 degrees east of the star Gamma Pegasi (Algenib, the southeastern "corner" of the "Great Square" of Pegasus), and is traveling towards the east-southeast at approximately 40 arcminutes per day; it remains in Pisces until almost the very end of 2020 before crossing into northern Cetus just before the beginning of 2021. Although still a week away from perihelion passage, the comet went through opposition back in September and was nearest Earth (0.49 AU) on November 3 and, ostensibly, is probably as bright as it is going to get. However, several short-period comets exhibit some kind of asymmetry with respect to perihelion in their brightness behavior, and meanwhile this particular comet is the closest it has been to the sun in almost nine decades, thus it is entirely possible that it may brighten further during the coming few weeks. It is equally possible, of course, that it will now commence fading, and the two observations I have now will be the only two that I will make. We will have to see what happens, and with the moon now entering the evening sky it probably will not be until December that I will be able to tell what the comet is doing.

The comet's next return, in 2026 (perihelion early November), is also very favorable, and it comes even closer to Earth (0.40 AU). After that, additional approaches to Jupiter will decrease the perihelion distance to 1.2 AU but will move the perihelion time away from the current favorable configuration; while the return in 2032 (perihelion mid-October) is moderately favorable none of the remaining returns in the 21st Century will provide decent viewing conditions. As I have described elsewhere in this space, my future of comet observing is uncertain after the near term; it is conceivable that I might still be active at some level in 2026 and thus might see the comet then, but I certainly have no expectations of seeing it again after that. I'm glad that I was finally able to snag this long-lost renegade comet for my tally before wrapping everything up.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 November 15.10 UT, m1 = 14.0, 1.2' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

690. COMET 141P/MACHHOLZ 2 Perihelion: 2020 December 16.27, q = 0.808 AU

Throughout all my various tabulations here over the years, the name of Don Machholz has come up on several occasions. An amateur astronomer who has spent most of his life in California (although he relocated to northwestern Arizona last year), Don began visually hunting for comets in 1975, and has as of now discovered 12 of them, the most visual discoveries of any person currently alive. His three most recent discoveries have come in the teeth of the comprehensive survey programs that became operational two decades ago, and it is conceivable that his most recent one -- Comet Machholz-Fujikawa-Iwamoto C/2018 V1 (no. 655) -- could be the last comet ever to be discovered visually, although if any more such discoveries are ever made, since he continues to pursue this endeavor I would not be at all surprised if he is the one making them. I have known Don personally since the early 1980s and consider him a good friend, and I have had the pleasure of confirming several of his discoveries.

Among Don's various comets are two short-period objects, both of which have approximate orbital periods of 5 1/4 years and both of which are immensely interesting scientifically. The first of these, 96P/Machholz 1, has shown up twice in previous tabulated tally entries, during its returns in 2007 (no. 405) and in 2012 (no. 507), and I discuss its importance in those entries. It returned again in 2017 but was poorly placed for observation -- impossibly placed from the northern hemisphere, although some observers in the southern hemisphere managed to observe it before perihelion passage -- and is poorly placed again at its next return, in 2023 (perihelion late January); since I managed a couple of observations during the similar return in 2002 (no. 300) it's at least conceivable that I might see it again then. The return after that, in 2028 (perihelion mid-May), is very favorable for the northern hemisphere, and if I'm still actively observing comets at that time I should certainly grab some additional observations then.

Don discovered his second periodic comet in mid-August 1994 (no. 193), the second of three comets he discovered within a span of just over three months. Other than being unusually bright (10th magnitude) for a previously-unknown short-period comet, initially there didn't seem to be anything unusual about it, however two weeks after its discovery it dramatically brightened, to about 7th magnitude. Then, Michael Jaeger in Austria -- a name that appears quite frequently within my tally entries -- discovered a "companion" comet following along with the primary one. Over the next couple of weeks as many as three additional "companions" appeared, and although most of these disappeared within a short period of time, Jaeger's companion -- which began to exhibit signs of fragmentation -- actually brightened for a while as the primary faded, and for a time the two objects appeared as a "double comet," somewhat reminiscent of the descriptions of Comet 3D/Biela before that object disintegrated in the mid-19th Century. Both comets eventually faded away, and meanwhile after analyzing their behavior and orbital motions Zdenek Sekanina concluded that the primary comet had split up during the previous return.

I wasn't at all sure that there would be anything to see at the subsequent return in 1999, but the primary comet was duly recovered in early August of that year -- right at the time I was engaged in my first "science diplomacy" visit to Iran -- and Jaeger's companion comet was recovered 2 1/2 months later. For a time Jaeger's companion comet was the brighter of the two, and in fact I picked it up one day before I picked up the primary component (no. 273). Jaeger's companion faded over the course of the next month, however, and meanwhile the primary brightened to 10th magnitude before fading away in early 2000. I happened to observe it on the evening of January 1, 2000, and it has the personal distinction of being the first comet I observed during a year that begins with "2."

Comet Machholz 2 returned again in early 2005; the viewing geometry was quite poor, but I managed to make a handful of observations at a low elevation (no. 368), when it appeared as a dim, vague, diffuse object near magnitude 12 1/2. No companion comets were detected at that return. The viewing geometry in 2010 was even worse, and the comet was not recovered. At the following return, in 2015, the viewing geometry was similar to that in 1994, and I managed to observe it again on a few occasions (no. 581), although it was quite a bit dimmer than it was in 1994, never appearing brighter than about 12th magnitude. A faint companion comet, apparently different from any that had been detected previously, accompanied the main comet and was imaged by numerous observers.

The viewing geometry this year is quite similar to that in 1999, the respective perihelion dates being just a week apart. It was recovered on August 13, 2020 by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii, and over the next three nights was imaged at two other institutions; all reported it as being a very faint, stellar object near magnitude 21.5. Somewhat surprisingly, there were no reported observations of any kind for the next 3 1/2 months (although I would later learn it had been imaged by a handful of institutions in early November, still as a very faint object of magnitude 20 or 21), and towards the end of that time I tried taking images a few times with the Las Cumbres Observatory network, without success. (It's worth noting that for much of that time, the comet was traveling through very dense Milky Way star fields north of Sagittarius.) Finally, on the evening of December 3 I submitted another set of images to the Las Cumbres network, and these clearly showed the comet as a diffuse and somewhat condensed object of 16th or 17th magnitude. After I reported these observations other observers also began reporting successful attempts at taking images, and meanwhile I also started making visual attempts, athough inititally these were unsuccessful. The various reports I read and images I saw seemed to suggest that the comet was brightening fairly rapidly, and another set of images I took on the evening of December 8 showed that this was true. On the following evening, December 9, I successfully detected the comet visually as a vague and diffuse object of 14th magnitude, that exhibited distinct motion during the half-hour that I followed it.

Coinciding with this rise in brightness, on December 7 Jaeger reported the presence of two faint companion comets, both of them traveling ahead of the main comet, and their presence has now been verified by other observers. Whether these are "new" companions, or instead are two of the previously-seen companions becoming bright enough to be visible again, remains undetermined at this writing.

At this time Comet Machholz 2 is in the southwestern evening sky, in western Aquarius a couple of degrees east of the star Epsilon Aquarii, and is traveling almost due eastward at 70 arcminutes per day. Perihelion passage is just a few days away but the comet continues to approach Earth afterwards, being closest (0.53 AU) on January 19, 2021; throughout this time it tracks eastward across Aquarius until entering Cetus on January 10 and into northern Eridanus at the beginning of February, and meanwhile its motion gradually accelerates (reaching a peak of two degrees per day when nearest Earth) while slowly curving northward. Given the comet's behavior at previous returns, it is difficult to predict what to expect in terms of its brightness; it may continue to brighten some over the near-term future, but while it might remain visually detectable until around the time of its closest approach to Earth it may very well fade rapidly afterwards, and I doubt if I'll be able to detect it after about the end of January. The two recently-discovered companions, meanwhile, are both much fainter, and will likely remain too faint for visual observations, although it is conceivable that one or both of them (or even perhaps one or more additional companions that could theoretically appear within the near future) might brighten unexpectedly.

While, as I mentioned above, I might see Don's first periodic comet again during one or two future returns, I rather doubt I will see this one again after its current return. The next return, in 2026 (perihelion late April) is very unfavorable, while the one after that, in 2031 (perihelion mid-August), is moderately favorable, similar to that in 2015, although if the comet continues to fade intrinsically it may not be visually detectable then, even if I am still active at some level at that time. The following return, in 2036 (perihelion mid-November) is very favorable, with the comet's passing just 0.125 AU from Earth a month after perihelion; unfortunately for those of us in the northern hemisphere, it will be traveling through southern circumpolar skies around that time, and passes just three degrees from the South Celestial Pole. Of course, as I've indicated in numerous previous entries, I consider it quite unlikely that I'll still be actively observing comets -- at least, visually -- at the age of 78, although I suppose I'll have to see what the future holds.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 December 10.09 UT, m1 = 14.1, 0.8' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (March 5, 2021): After reaching a peak brightness near 11th magnitude during the first half of January 2021, Comet Machholz 2 faded distinctly towards the end of that month, and I lost sight of it after the beginning of February. However, on March 3 the ATLAS program in Hawaii recorded it in a state of apparent outburst, which was soon verified by various observers elsewhere. An image I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory network on the night of March 4-5 clearly showed the comet exhibiting an appearance consistent with the reports I had read, and a couple of hours later I successfully observed it visually, as a diffuse, "soft" object just brighter than 14th magnitude.

Comet Machholz 2 is presently located in central Orion about four degrees north of the "belt" stars, and traveling just northward of due east at slightly under one degree per day; it crosses into Monoceros during the fourth week of March and on the 25th and 26th it crosses the northern regions of the Rosette Nebula (NGC 2237). As for its brightness, if it follows a typical post-outburst cometary behavior the comet will likely fade and diffuse out during the near- to intermediate-term future, and it is rather likely that last night's observation will be my only one of this outburst and my final one of this comet during its present return. Unless, of course, it undergoes another outburst sometime soon, which considering this comet's behavior throughout its observational history is at least theoretically possible . . .

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 March 5.14 UT, m1 = 13.7, 0.8' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center