TALLY ENTRIES 691-700

I have now entered the "home stretch" on the approach to lifetime comet number 700. I do so with a comet discovered by the ATLAS survey on September 12, 2020 (and independently that same night by the Pan-STARRS survey), at which time it was a very dim object of about 19th magnitude. I have had expectations of eventually seeing this comet, although for the most part it has remained quite faint ever since its discovery; however, several days ago amateur astronomer Taras Prystavski in Ukraine reported that, according to images he had taken, it had apparently brightened quite rapidly within the recent past. Upon reading his report I obtained a pair of images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network which showed that the comet was indeed bright enough to be worth attempting visually, however when I did so on the evening of December 13 I was unable to see anything convincing. Over the next couple of days I saw additional images that suggested that the comet was continuing to brighten, and when I tried again on the evening of the 15th I successfully detected it as a vague and diffuse object slightly fainter than 13th magnitude.

This particular Comet ATLAS is traveling in a shallowly-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 164 degrees, i.e., 16 degrees with respect to the ecliptic) and appears to be an intermediate-period object with an approximate orbital period slightly less than 1000 years. At the time of my initial observation it was fairly low in my southwestern evening sky, at an elongation of 54 degrees in eastern Capricornus (and just a little over two degrees south of Comet 88P/Howell (no. 678)), and with a general westward motion its elongation is dropping by over a degree per day. It is entirely possible that this will be my only observation prior to its disappearing into twilight, since the moon is now moving into the evening sky, and by the time the moon exits the evening sky during the early days of January 2021 the comet's elongation will have dropped to just a little over 30 degrees. In any event it is lost in twilight shortly thereafter.

The comet is in conjunction with the sun at the beginning of February, and for about two weeks around that time will be in the field-of-view of the LASCO coronagraphs aboard SOHO, although it will likely be too faint to be detected. It begins emerging into the morning sky in early March, when it will be located in far western Aquarius; it will be traveling towards the northwest, initially rather slowly, but accelerating as it approaches Earth. Over the coming weeks the comet tracks across Aquila, Hercules, Corona Borealis, Bootes, Canes Venatici, and Leo, reaching a peak northerly declination of +33 degrees in late April -- when it will also be at opposition -- before beginning to curve southward. It is nearest Earth (0.46 AU) on April 23, at which time it will traveling at close to 4 1/2 degrees per day, although it slows down rather rapidly afterwards, to just over 20 arcminutes per day by the end of May (when it will be located a couple of degrees northwest of the star Delta Leonis).

As is always the case with long-period comets, any brightness predictions for Comet ATLAS would be somewhat problemetical, but the fact that it has been around the sun at least once before, combined with its recent rapid brightening, suggests that it could be around 11th magnitude when it appears in the morning sky in early March, and perhaps as bright as 9th or 10th magnitude when it is closest to Earth. I suspect it might begin fading fairly rapidly after that, and will probably drop below visual detectability around the beginning of June.

Meanwhile, my entry into the "home stretch" towards comet number 700 did not end with this comet . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 December 16.07 UT, m1 = 13.3, 1.3' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (March 11, 2021): The initial observation I obtained of Comet ATLAS in mid-December 2020 was indeed the only observation of it I made prior to its disappearing into evening twilight. To the best of my knowledge there were no reported detections of it in the LASCO coronagraphs aboard SOHO when it was near conjunction with the sun in early February, and meanwhile as expected it began emerging into the morning sky in early March. I obtained my first post-conjunction observation on the morning of March 11, when -- in keeping with the prediction I made above -- it appeared as a relatively condensed object of 11th magnitude.

At present Comet ATLAS is located in northwestern Capricornus some four degrees northeast of the naked-eye optical double star Alpha Capricorni, and is traveling towards the northwest at somewhat over 20 arcminutes per day. As it approaches Earth over the next few weeks it accelerates, and follows the path I describe above. Its overall brightness behavior may also follow the general scenario I describe above, which suggests I should be able to follow the comet visually for another two to three months.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 March 11.50 UT, m1 = 10.8, 1.7' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

692. COMET ATLAS C/2019 L3 Perihelion: 2022 January 9.62, q = 3.555 AU

The cometary activity in the evening sky during this month of December 2020 has been very busy, with well over half a dozen comets that I presently have under observation; it generally takes me two or three nights to get satisfactory observations of all of them. On the evening of December 15, I observed four comets, beginning with my initial observation of the previous entry; 2 1/2 hours later, after observing two previously-added comets, I concluded the evening by adding this particular comet to my tally. This is the 37th time, and the second time in 2020, that I have added two or more comets in the same night.

This is yet another discovery by the ATLAS survey, which found the comet as far back as June 10, 2019, at which time it was about 19th magnitude and located at a heliocentric distance of 8.46 AU. It has brightened steadily since then, and various images and reports I've seen over the past few months suggested it was bright enough for visual attempts, and I began making these around mid-October, although these were unsuccessful. (The rich Milky Way star fields in Cassiopeia that the comet has been traveling through have made attempts rather problematical at times.) I made an additional unsuccessful visual attempt in early December, but on this attempt -- when the comet was located in a "clean" star field -- I managed to detect it as a very faint, almost starlike object (with just a trace of diffuseness) near magnitude 14 1/2.

Comet ATLAS is traveling in a moderately-inclined direct orbit (inclination 48 degrees) and is at a present heliocentric distance of 4.9 AU and still over 12 1/2 months away from perihelion passage. (Among long-period comets on my tally, this is the 9th-longest interval before perihelion when I have first picked up a comet.) It is currently located about one degree southwest of the star Beta Cassiopeiae (the western-most star of the "W" of Cassiopeia) and is traveling slowly towards the southeast. It spends the next few weeks tracking across the southern part of that constellation, before crossing into northwestern Perseus (and turning more directly eastward) in early March 2021. It gradually sinks lower into the north-western evening sky, and after passing slightly less than one degree north of the star Alpha Persei in early May it is in conjunction with the sun (30 degrees north of it) a week after the middle of that month.

The comet starts to emerge into the morning sky around early August, at which time it will be located a few degrees north-

east of the star Beta Aurigae. It travels towards the east-southeast from there, crossing into Lynx in early September, and then begins to turn more directly southward, passing through its stationary point in early November and crossing into Gemini in mid-December. The comet is at opposition in early January 2022, around the same time that it is passing through perihelion, and will be located some four degrees southeast of the star Theta Geminorum and traveling towards the southwest at slightly over 15 arcminutes per day. Over the next few weeks it curves more towards the south and passes through its other stationary point in early March before eventually resuming its motion towards the east-southeast; it crosses into Canis Minor in early May and disappears into evening twilight over the next month. After being in conjunction with the sun near the end of July the comet emerges back into the morning sky towards the end of September, when it will be located a couple of degrees south of the star Alpha Hydrae; from that point it tracks southeastward through Hydra, eventually turning southward and passing through its stationary point in early December, crossing into Antlia during the middle of that month, and going through opposition again in mid-February 2023.

Based upon my observations of previous large-q long-period comets, I suspect Comet ATLAS will brighten slowly over the coming months, perhaps being close to 13th magnitude by the time it disappears into evening twilight around May. It may be close to that same brightness when it emerges into the morning sky in August, brightening to a peak brightness near 12th magnitude when it is near perihelion before fading back to 13th magnitude by the time it disappears again into the dusk. If the comet is still visually detectable when it emerges into the morning sky during the latter months of 2022 it will probably be no brighter than 14th magnitude, and I suspect it will fade beyond visual range by perhaps the beginning of 2023.

In my introductory comments to "Continuing With Comets" I mentioned that my plans at that time (mid-2017) included continuing with my high level of observational activities at least until I reached my 500th separate comet. It so happens that this Comet ATLAS is separate comet no. 491, which means that I am now on the "home stretch" towards that goal (in addition to being on the "home stretch" to lifetime comet no. 700). There aren't any "repeat" periodic comets that I expect to add to my tally until about mid-May 2021, so any additions that I might make over the next few months will likely be new separate comets as well. I will probably reach both goals sometime around the middle of 2021, and . . . whether or not I might start slowing down after that point, as I hinted I might do in those introductory comments, is the proverbial bridge that I will cross when I arrive there.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2020 December 16.18 UT, m1 = 14.4, 0.3' coma, DC = 7-8 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (August 8, 2021): After I picked up Comet ATLAS in mid-December 2020 it brightened fairly rapidly to about magnitude 13 1/2 by early February, and then remained near that brightness for the next two months before it became too low in the northwestern sky for me to observe. Following its conjunction with the sun it began emerging into the morning sky by around early August, and on the morning of the 6th I successfully picked it up somewhat low in my northeastern sky, four degrees northeast of the star Beta Aurigae; it had distinctly brightened during the interim, and appeared as a relatively condensed object of magnitude 12 1/2.

The rest of the apparition should proceed pretty much as described above. Since it is currently running a bit brighter than expected, it may reach a peak brightness around magnitude 11 to 11 1/2 when near perihelion passage in January 2022.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 August 6.42 UT, m1 = 12.4, 0.9' coma, DC = 6-7 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (November 2, 2022): Perhaps a little bit surprisingly, Comet ATLAS achieved a peak brightness slightly brighter than 10th magnitude around the time of perihelion passage in January 2022. It had faded by a little over a magnitude by the time I stopped following it during the latter part of April, by which time it was starting to get low in my western evening sky. I thought I was probably done with it, however when it started emerging into the morning sky in October I read reports and saw images that suggested it was still bright enough to be visually detectable without difficulty and, sure enough, when I attempted it on the morning of November 2 I easily saw it as a small and moderately condensed object of magnitude 11 1/2.

Comet ATLAS is currently located in western Hydra some four degrees south of the star Upsilon-1 Hydrae and is traveling towards the south-southeast at 15 arcminutes per day. I describe its future motion above, although it's fair to mention that when near opposition in February 2023 it will be located at a declination of -35 degrees. For the time being it is coming closer to Earth, with a minimum distance of 4.27 AU taking place in late January. The comet should maintain something close to its present brightness for the next couple of months, although once it begins pulling away from Earth it will probably start to fade somewhat rapidly. In all honesty, given its placement fairly low in my southern sky and the fact that it is already well past perihelion I will likely observe it only infrequently, and perhaps hardly at all once it is past opposition.

Incidentally, with this latest observation Comet ATLAS is now in 6th place on the list of longest observational interval of all the long-period comets on my tally (and in 14th place among all the comets I have observed). If I end up following it until around the time of its opposition it will go up one place on both of those lists.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2022 November 2.46 UT, m1 = 11.5, 1.4' coma, DC = 5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

693. COMET 414P/STEREO P/2021 A3 Perihelion: 2021 January 25.39, q = 0.526 AU

The new year of 2021 has now arrived. From a national and international perspective the new year arrives at a time of great anxiety, in significant part due to the global coronavirus pandemic that has as of now claimed over 2 million lives worldwide and 400,000 lives here in the U.S. The recent development of vaccines brings hope that this calamity will eventually begin to recede, although even at best it will be several months before things can start returning to some sense of "normal," and in any event whatever new "normal" emerges is likely to be somewhat different from the pre-pandemic one. Meanwhile, here in the U.S. there is a profound feeling of shock and dismay following the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6 and its aftermath; while I would like to think that some national healing can begin following the inauguration of the new President later this week, that process will likely be a long and at times painful one.

From my own perspective, I guess I am fortunate that I am in both a physical location and at a place in my life where, to a non-trivial degree, I am largely unaffected by the goings-on in the larger world (although the pandemic has introduced some distinct changes in how I conduct my social life, and I have very seldom left my residence during the past several months). Now that I am finished with "Ice and Stone 2020" I have been taking some "down time" as I contemplate how I might want to proceed from here; I would like to think that there are some things I can do that can help address some of the underlying educational issues that, among other things, contributed to the horrifying events at the U.S. Capitol, but for the time being I am unclear in my mind as to what these might be. I will keep working at it . . . I can't let myself not do so.

Meanwhile, I continue to remain active in comet observing in this new year, as I approach the goals (that I've mentioned in previous entries) of my 700th overall comet and my 500th separate comet. I carried over quite a few of the comets I was following late last year, and meanwhile I have already begun adding new comets to my tally. My first tally addition of 2021 is an object discovered on January 4, 2021 by the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) survey in California, at that time a faint 19th magnitude apparent asteroid which, however, began brightening rapidly and exhibiting cometary activity within a few days. At around that same time German amateur astronomer Maik Meyer determined that the ZTF comet is in fact identical to a comet that had been detected in May 2016 by researcher Scott Ferguson in images taken by the Heliospheric Imager and one of the coronagraphs aboard the STEREO-A spacecraft. The comet appeared in over a hundred STEREO images over a two-day period that allowed the calculation of an uncertain orbit with an indicated period of 7.7 years; despite attempts by several observers, no one succeeded in recording it in any ground-based images. Meyer's identification of the ZTF comet with the STEREO comet -- which had been assigned the designation P/2016 J3 -- shows that the comet's true orbital period is a significantly shorter 4.67 years.

Comet STEREO was already fairly low in the southwestern evening sky -- elongation 44 degrees -- and getting lower at the time of its re-discovery by ZTF. Over the subsequent days some of the image reports suggested it might have been as bright as 14th magnitude, and I made a visual attempt on the evening of January 8; while at times I thought I might possibly be glimpsing "something" I was unable to convince myself that I was detecting any valid suspect. Additional reports afterwards suggested that the comet was continuing to brighten fairly rapidly, and when I tried again on the evening of January 12 I successfully observed it as a small and somewhat condensed object near magnitude 13 1/2; by that time the elongation had shrunk to 36 degrees and in addition to the comet's low elevation I also had to contend with moderately bright zodiacal light.

This will almost certainly be my only observation of Comet STEREO. The moon has now emerged into the evening sky, and meanwhile the comet's elongation continues to decrease, having now dropped below 30 degrees and dropping below 25 degrees on January 22. Following perihelion passage on the 25th the comet is closest to Earth (0.50 AU) on February 3 and is in conjunction with the sun (28 degrees south of it) four days later. It is conceivable that observers in the southern hemisphere may be able to detect it in the morning sky starting around mid-February, when it will be traveling through the constellations of Indus and Telescopium near a declination of -50 degrees; it will likely fade quite rapidly and its period of visibility will be rather short.

I also have no expectations of seeing Comet STEREO on any future returns. The next two returns (perihelion passages in mid-September 2025 and late May 2030) are unfavorable, and while the return in 2035 (perihelion mid-February) is fairly similar to this year's, it would still be a difficult object to observe, and even if I am still alive at that time I will very likely have "retired" from visual comet observing long before then. Especially due to its unusual history and its overall elusiveness I am glad I was able to grab at least one visual observation of this comet before all is said and done.

OBSERVATION: 2021 January 13.07 UT, m1 = 13.6, 0.8' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (February 23, 2021): Comet STEREO has now emerged into the southern hemisphere's morning sky, but I am not aware of any positive detections of it. I have read, however, of one unsuccessful attempt to image it which in turn suggests that it is fainter than 19th magnitude. The available data from 2016 (such as it is) and its pre-perihelion behavior earlier this year seem to suggest that the comet brightens and fades very rapidly, so perhaps this isn't too much of a surprise.

The newest batch of Minor Planet Circulars (officially dated January 27, but just released today) assigns the short-period comet designation 414P to Comet STEREO, and I have now reflected this in the entry title. Even though most newly-numbered periodic comets these days are far too faint for me to detect visually, this is actually not my highest-numbered observed comet; Comet LINEAR P/2010 A5, which I successfully observed during its discovery return (no. 476) as a part of "Countdown," has recently been recovered on its next return, and has been assigned the designation 418P -- the highest-numbered designation at this writing.

694. COMET A/2018 V3 Perihelion: 2019 September 8.70, q = 1.340 UT

For the 10th time during my years of visual comet observing, I have now retroactively added an object to my lifetime comet tally (although on three of those occasions I did so while the object in question was still under observation). This particular object, which I discussed in some detail in an earlier tally entry, was discovered on November 12, 2018 by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii, at which time it was a very faint stellar-appearing object of 21st magnitude. Calculations soon revealed that it was located 4 AU from the sun and traveling in an orbit reminiscent of a long-period comet -- although, since it didn't exhibit any cometary activity at the time, it was assigned an "A/" designation -- with an inclination of 165 degrees (i.e., 15 degrees with respect to the ecliptic, but retrograde) and an approximate orbital period of 1340 years. Shortly before perihelion passage it would be passing by Earth (minimum distance 0.37 AU on August 18, 2019, at which time it would also be at opposition) as it and Earth rapidly flew past each other while going in opposite directions.

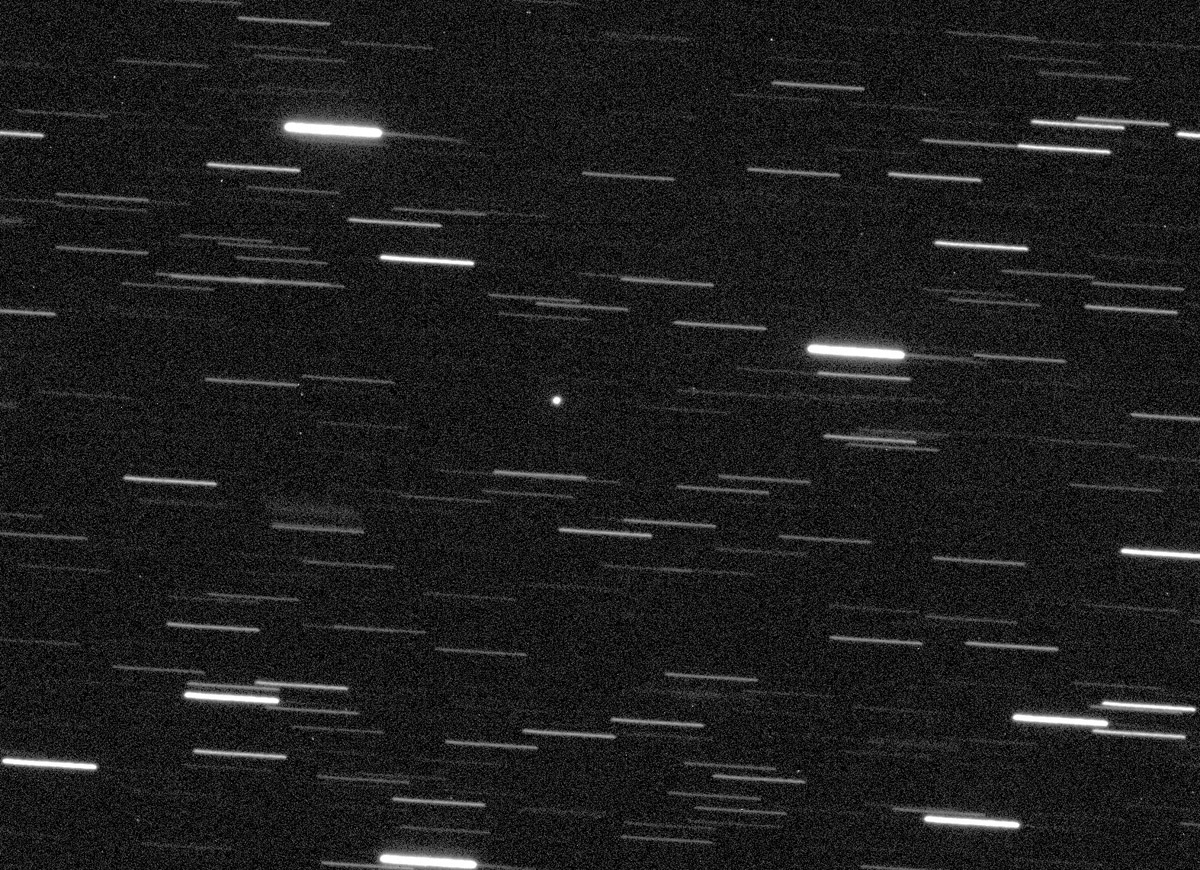

A/2018 V3 was in conjunction with the sun during the latter part of April 2019, and after it began emerging into the morning sky I started attempting to take images of it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network around the end of May. At first these attempts were unsuccessful, but on June 28 I finally was able to record it as a very faint, starlike object. I continued taking images of it during the ensuing weeks as it slowly brightened, although it continued to remain completely stellar in appearance. I made my first visual attempt on the morning of August 12 and managed to glimpse it as an extremely faint starlike object of 15th magnitude. Over the next week and a half -- during which time I had to contend with moonlight (full moon being on the 15th) and typical monsoon conditions -- I was able to observe it on three additional occasions, the last of these being on the evening of August 22; on each of these it appeared at 15th magnitude and remained stellar in appearance. During this time it was traveling rapidly west-southward through Aquarius, Piscis Austrinus, Microscopium, and eastern Sagittarius, reaching a peak apparent speed of 5 1/2 degrees per day when it was closest to Earth and a peak southerly declination of -31 degrees a few days later. After my final visual observation A/2018 V3 began traveling through the dense star fields of the Sagittarius Milky Way and I didn't look for it any further; I did, however, continue taking images with the LCO network, with my last set being taken on September 24, by which time it had become distinctly fainter and was still continuing to exhibit a stellar appearance.

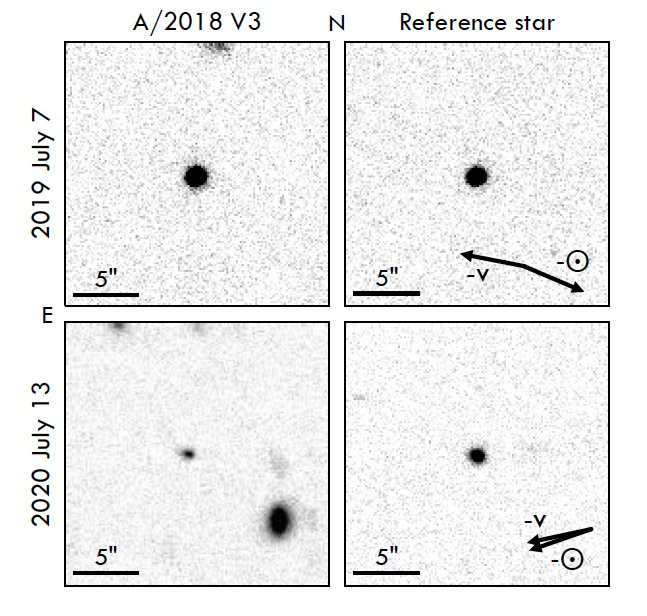

Reports from all other observers also indicated that A/2018 V3 remained asteroidal throughout its apparition, and thus was never an active comet -- and accordingly ineligible for inclusion in my tally -- despite its distinctly cometary orbit. There the matter stood until just a few days ago, when in mid-January 2021 a team of astronomers led by Caroline Piro at the University of Hawaii published a paper announcing results from their study of the object. Their observations indeed indicated that A/2018 V3 remained entirely asteroidal in behavior around the time of its perihelion and passage by Earth -- although photometric studies indicated that it has the very dark surface that is expected of a cometary nucleus -- however a set of "stacked" images taken with the 3.6-meter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) at Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii taken on July 13, 2020 (at which time A/2018 V3 was over ten months past perihelion and located at a heliocentric distance of 4.08 AU) reveals a distinct elongation in roughly the east-west direction, consistent with the direction expected of a cometary tail. A detailed analysis of the brightness profile of this image is consistent with a tiny level of activity at that time (with less than 0.01% of the nucleus' surface being active). While the evidence is perhaps not extremely compelling, in my mind it is strong enough that, for tally purposes, I can consider A/2018 V3 as a comet; indeed, there have been other objects that have been formally designated as "comets" that have not been much more active than this.

LEFT: An image of A/2018 V3 I took on August 20, 2019 via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. RIGHT: Figure 2 from the paper by Piro et al. (2021). It shows "stacked" images of A/2018 V3 (left column) and representative field stars (right column) taken with the 3.6-meter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) at Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii on July 7, 2019 (top row) and July 13, 2020 (bottom row). A/2018 V3's asteroidal appearance on the former date and elongated appearance on the latter date is obvious.

LEFT: An image of A/2018 V3 I took on August 20, 2019 via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. RIGHT: Figure 2 from the paper by Piro et al. (2021). It shows "stacked" images of A/2018 V3 (left column) and representative field stars (right column) taken with the 3.6-meter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) at Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii on July 7, 2019 (top row) and July 13, 2020 (bottom row). A/2018 V3's asteroidal appearance on the former date and elongated appearance on the latter date is obvious.

A/2018 V3 is apparently a representative of a recently-identified class of solar system object that have been dubbed "manx" objects, after the tailless cats indigenous to the Isle of Man. These are objects in long-period orbits typical of comets, but are at most only very weakly active; these include the "comets" I mentioned in the previous paragraph. Only a relatively small handful of these objects have thus far been identified, and the role they play in the evolution of the solar system as well as their implication for planetary defense -- both of which are discussed in the Piro et al. paper -- are active areas of research at this time. As the "deeper" survey programs continue to come on-line and operate during the years ahead they will likely continue to detect manx objects, although since these tend to remain very faint, unless they come close to the sun and/or Earth as A/2018 V3 did it is unlikely that I'll be seeing very many of them.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2019 August 12.43 UT, m1 = 15.1, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

FINAL OBSERVATION: 2019 August 23.20 UT, m1 = 15.1, 0.0' coma, DC = 9 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

695. COMET NEOWISE C/2021 A2 Perihelion: 2021 January 22.63, q = 1.413 AU

I discuss the NEOWISE mission, the follow-up endeavor of the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) spacecraft, in an earlier tally entry. Including this comet, NEOWISE has thus far contributed seven comets to my lifetime tally, by far the best of these being C/2020 F3 (no. 676) which became a spectacular naked-eye object last July. One month later NEOWISE discovered another comet (C/2020 P1) which, with a perihelion passage in late October and a small perihelion distance of 0.34 AU, also showed some promise of becoming somewhat bright. Initially located in southern circumpolar skies, it brightened somewhat slowly, eventually reaching about 9th magnitude before disappearing into sunlight in early October. Unfortunately, it apparently disintegrated as it passed through perihelion, and when it emerged into the northern hemisphere's morning sky towards the end of that month nothing remained except a thin wisp of material, which moreover stayed at a fairly small elongation from the sun. I successfully imaged it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network shortly after its discovery but never made any visual attempts for it.

The beginning of 2021 has been a very productive time for NEOWISE discoveries; at this writing three NEOWISE comets have already been announced and a fourth one currently on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page (PCCP) is awaiting a formal announcement. The first of these was discovered on January 3, somewhat deep in southern skies near a declination of -51 degrees; the initial reports suggested it was somewhat bright (around 15th magnitude), and I successfully took some images of it on the 6th via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, the astrometric measurements of these (performed by my British colleague Richard Miles) appearing on the discovery announcement that was issued on the 10th. Some reports of visual observations by observers in the southern hemisphere suggested it was bright enough for me to attempt visually, although I had to wait until it had traveled far enough north to make such an attempt worthwhile (in addition to having to contend with the rich Milky Way star fields that it is currently traveling through). On the morning of January 15 (when its declination was just north of -46 degrees) I successfully observed it as a small and slightly condensed object of 13th magnitude, with this same overall appearance being exhibited when I saw it again three mornings later. The visual reports from the southern hemisphere, where it is significantly higher in the sky than it is from my location, indicate that it may be up a magnitude or so brighter than this and that the coma is also somewhat larger than what I have been able to detect.

This particular Comet NEOWISE is traveling in a steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 107 degrees) and is currently just a few days away from perihelion passage. It is presently located in northern Vela near the star Psi Velorum and is traveling towards the northwest at slightly over 1 1/2 degrees per day, although as it goes through opposition in late January and passes closest to Earth on February 3 (minimum distance 0.51 AU) it accelerates (to a peak rate of 3 1/2 degrees per day around the time of closest approach before slowing down) and curves more towards the north-northwest. Throughout this time it travels roughly parallel to the Galactic Equator (and thus remains within rich Milky Way star fields) as it passes through the constellations of Pyxis, Puppis, Monoceros, Orion, and eastern Taurus, before entering Auriga during the fourth week of February, where it remains for the next 2 1/2 months. When nearest Earth it may be a half- to a full magnitude brighter than it is now, and thereafter will probably fade beyond the range of visual detectability by sometime in March.

As for the other recently-discovered NEOWISE comets, C/2021 A4 passes through perihelion shortly after mid-March and appears to be an intermediate-period object with an orbital period near 400 years; thus far it has remained quite faint, but it possibly may become visually detectable when it passes 0.44 AU from Earth shortly before mid-February. C/2021 A7, which passes through perihelion in mid-July, conceivably could become visually detectable in April and/or May but will be low in my southwestern sky after dusk. According to a very preliminary orbit the apparent NEOWISE comet still on the PCCP passes through perihelion in mid-March and will pass 0.6 AU from Earth in mid-February (at which time it will be in northern circumpolar skies), but thus far it appears to be an intrinsically dim object and it may very well remain too faint for visual observations. As always, of course, any of these comets that I do manage to observe will show up in my tally as future entries.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 January 15.44 UT, m1 = 13.0 (extinction corrected), 1.0' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

696. COMET NEOWISE C/2021 A4 Perihelion: 2021 March 20.03, q = 1.146 AU

In the preceding entry I discuss the unusually prolific set of comet discoveries by the NEOWISE mission during January 2021. The PCCP comet mentioned there has now been announced as C/2021 A10; it appears to be an intermediate-period object with an approximate orbital period between 800 and 900 years, but also appears to exhibit only marginal cometary activity, and even though it passes slightly within 0.6 AU from Earth this coming week it will likely remain very faint. Meanwhile, NEOWISE discovered yet another comet (the fifth) during January, C/2021 B3; this seems to be a Halley-type comet with an approximate orbital period of 170 years. It passes perihelion in mid-March at a heliocentric distance of 2.2 AU and will likely remain faint; it is presently in southern circumpolar skies and even though it does come northward it remains fairly deep in my southern sky, and I have no expectations of looking for it.

NEOWISE discovered this comet on January 3, a little less than 22 hours after its initial observation of the previous comet. As I mentioned in the above entry this is an intermediate-period object, with the most recent calculations indicating an orbital period right around 300 years. Although the early observations indicated it was a very faint object near 19th magnitude, I've noticed over the years that Halley-type and intermediate-period comets often brighten rapidly as they approach perihelion, and indeed some of the recent reports suggested it was doing so. Especially with its current proximity to Earth I considered it worth attempting visually, and sure enough, on my first attempt, on the evening of February 5, I successfully detected it as a vague and diffuse object near magnitude 12 1/2 which exhibited distinct motion during the 20 minutes that I followed it.

Comet NEOWISE is closest to Earth (0.43 AU) on February 12, and is currently at opposition. It is traveling in a steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 112 degrees) and presently is in northern circumpolar skies, in northwestern Ursa Major near a declination of +68 degrees. For the time being it is traveling almost due westward at a rapid four degrees per day, but once it has passed Earth it starts to turn towards the southwest and eventually almost directly southward, and also slows down; it travels through Camelopardalis, Auriga (passing two degrees southeast of the bright star Capella on February 17), Taurus (passing 40 arcminutes northwest of the bright star Aldebaran on February 28 and then crossing the eastern part of the Hyades star cluster), and (beginning in mid-March) northern Eridanus. Ostensibly the comet should be near its peak brightness over the next couple of weeks, however I would not be surprised if it brightened by another magnitude or more over the course of the next month as it continues to approach perihelion. By early April it will be starting to get somewhat low in my southwestern sky after dusk and by then it will also be receding from the sun as well as Earth, and I doubt that I'll be following it much beyond that time.

There are other inbound long-period comets, including possibly one of the other January NEOWISE discoveries, that I may potentially be adding to my tally within the not-too-distant future as I approach lifetime comet no. 700 and separate comet no. 500. Meanwhile, I have received one bit of interesting news in my personal life, as my younger son Tyler has informed me that I should become a grandfather sometime around mid-May. Since his partner already has a daughter from a previous relationship I have been a grandfather "of sorts" for the past couple of years, but this would be my first biological grandchild -- taking place when I'll be at the tender young age of 63 . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 February 6.16 UT, m1 = 12.6, 2.2' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

697. COMET PALOMAR C/2020 T2 Perihelion: 2021 July 11.15, q = 2.055 AU

I continue to approach lifetime comet no. 700. As I've indicated in earlier entries most of the comets I might be adding to my tally within the near-term future are long-period comets, and thus I am rapidly approaching my 500th separate comet as well. Since I can think of at least a few inbound long-period comets that I might be picking up before much longer, it now looks distinctly possible that I will achieve both goals before the mid-point of this year. After that, we'll see what happens . . .

This particular comet was discovered on October 7, 2020, by Dmitry Duev during the course of the Zwicky Transient Facility survey program that utilizes the 1.2-meter Schmidt telescope at Palomar Observatory in California -- hence, the name "Palomar." Afterwards, numerous pre-discovery images were identified in other surveys' data -- primarily the Pan-STARRS survey -- to as far back as December 2019, which in turn allowed for the early determination of a valid orbit. The comet was approximately 19th magnitude at the time of its discovery, and was of course expected to brighten as it approached the inner solar system, however I began reading reports that suggested it has brightened quite rapidly during the recent past, and a set of images I obtained with the Las Cumbres Observatory network on February 18 indicated that it had now brightened to the point where visual attempts were worthwhile. As things happened, a series of winter storms that dropped quite a bit of snow in the New Mexico mountains and produced the coldest temperatures (-10 degrees F, or -23 C) we have experienced in a decade -- and that wreaked a lot of havoc in Texas and other places to the east -- delayed any such attempts. Finally, on the early morning of February 20 -- when there was still a fair amount of snow on the ground -- I successfully observed the comet as a faint, small, moderately condensed object of 14th magnitude.

Comet Palomar is traveling in a rather shallow-inclined (inclination 28 degrees) elliptical orbit with an approximate orbital period of 6000 years (which will be shortened to a little over 4000 years following a distant approach to Jupiter (3.1 AU) in June 2022 on its way out of the inner solar system). It is presently located in southeastern Canes Venatici some seven degrees west of the star Rho Bootis, and is traveling slowly towards the northeast at it approaches its stationary point in mid-March. After that it travels westward back through southeastern Canes Venatici in a retrograde loop, being at its farthest north point (declination +34.4 degrees) in early April, at opposition shortly after the middle of that month, and closest to Earth (1.41 AU) during the second week of May. After that the comet passes slightly less than one degree west of the globular star cluster M3 on May 17 and crosses into Bootes one day later; after passing through its other stationary point just before the end of May it begins traveling towards the southeast, remaining in the southwestern part of that constellation before crossing into eastern Virgo in early July and into Libra in mid-August, by which time it will be starting to get somewhat low in my southwestern sky after dusk. Ostensibly, it should reach a peak brightness about a magnitude and a half brighter than it is now, i.e., somewhere around magnitude 12 1/2, during May and June, although as is true for just about any comet we will just to see what it actually does.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 February 20.35 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.6' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

698. COMET SWAN C/2021 D1 Perihelion: 2021 February 27.61, q = 0.902 AU

A loosely-knit international collaboration of comet astronomers -- which included me in a minor role -- ended up being responsible for the discovery and recognition of this comet. On February 25, 2021, Australian amateur astronomer Michael Mattiazzo reported the existence of a possible comet in several images taken by the SWAN ultraviolet telescope aboard the SOHO spacecraft going back to February 19. (Michael has discovered several previous SWAN comets, including the most recent one, C/2020 F8 (no. 680).) The potential comet was rather faint, not much above the detection limit of SWAN, and moreover was at a small elongation from the sun -- not much above 20 degrees -- which would make confirmation from the ground quite difficult; while it wasn't entirely clear that the object was even real, it nevertheless continued to appear to be present in subsequent SWAN images. French amateur astronomer Nicolas Lefaudeux took a wide-field image in twilight on the evening of February 27, although initially no convincing candidate for the possible comet could be found on it. Finally, on the following evening Krisztian Sarneczky at the Piszkesteto Station of the Konkoly Observatory in Hungary, Michael Jaeger in Austria, and Luca Buzzi in Italy all successfully imaged the comet, and from the very approximate SWAN data and Jaeger's images Maik Meyer in Germany was able to calculate a reasonable preliminary orbit; this in turn enabled me to identify it on Lefaudeux's image which then permitted the determination of a better orbit. Several observers from around the world succeeded in obtaining images over the subsequent days, and meanwhile Piotr Guzik in Poland and Sandor Szabo in Hungary independently managed to observe the comet visually on the evening of March 2, at which time its elongation was slightly under 25 degrees; they reported it as being between 11th and 12th magnitude, consistent with its appearance in the SWAN images. The comet's discovery was eventually announced on March 4.

This latest Comet SWAN is traveling in a direct (i.e., pro-grade) orbit with an inclination of 31 degrees; the latest calculations seem to suggest it is an intermediate-period object with an orbital period in the neighborhood of 900 years. It has remained on the far side of the sun from Earth throughout its appearance, and was still a somewhat distant 1.68 AU when nearest Earth on March 15. It has traveled northward and its elongation has slowly increased since its discovery, but it has remained quite low in the western sky; because of some nearby trees this is a bad direction from my primary observing location. Furthermore, a series of storms (both snowstorms and dust storms) during mid-March prevented me from making any attempts for the comet. Finally, on the evening of March 17 (by which time its elongation had finally increased to 30 degrees), through a gap in the trees I was able to view it for about two minutes, low above the horizon in twilight; it appeared as a moderately condensed object of 11th magnitude.

At this time Comet SWAN is located in northeastern Pisces a couple of degrees north of the star Phi Piscium and is traveling towards the east-northeast at approximately 80 arcminutes per day; it crosses into Triangulum on March 26 (passing just five arcminutes south of the star Alpha Trianguli two days later), into Perseus during the first week of April, and into Auriga just before the end of that month. Meanwhile, on April 23 it reaches its farthest north declination (+34.3 degrees) and also its maximum elongation (37 degrees).

With the moon's now being in the evening sky I don't expect to make any more observations of Comet SWAN during the current dark run. Since it is now receding from both the sun and Earth I expect it to fade during the coming weeks, although I hope that it is still bright enough to be visible once the moon clears from the evening sky at the end of March/beginning of April. At best, though, I will probably only obtain another two or three observations of this elusive comet before it heads back out into the outer solar system.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 March 18.09 UT, m1 = 11.2: (extinction corrected), 1.5' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

699. COMET PANSTARRS C/2017 K2 Perihelion: 2022 December 19.69, q = 1.797 AU

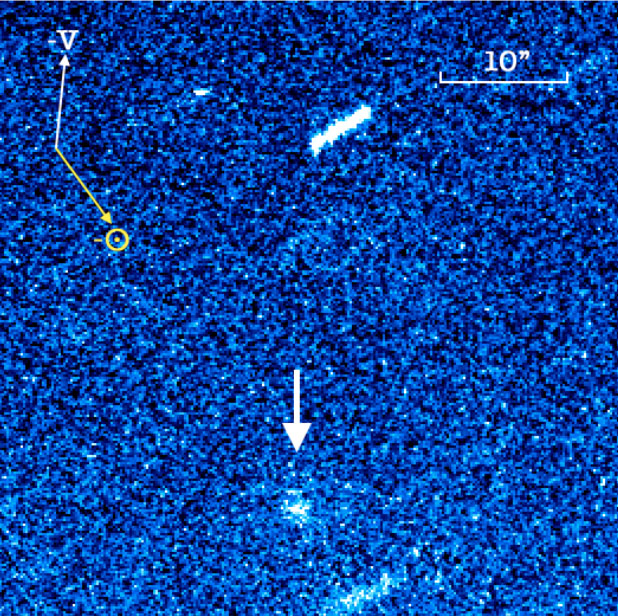

I have been waiting a long time for this comet . . . When discovered by the Pan-STARRS program in Hawaii back on May 21, 2017 it was a dim object of 19th magnitude, but was already clearly active despite being located at the enormous heliocentric distance of 16.09 AU. Orbital calculations were a bit problematical at first, but these eventually showed that the comet is traveling in an orbit nearly perpendicular to Earth's (inclination 88.5 degrees) and was over 5 1/2 years away from perihelion passage, which would be taking place at a much smaller heliocentric distance -- thus indicating the potential for a bright display. Once the orbit was nailed down, numerous pre-discovery images were identified, including some taken with the 3.6-meter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope at Mauna Kea as far back as May 12, 2013, at which time the comet was located at a heliocentric distance of 23.74 AU, well beyond the orbital distance of Uranus. Even at that distance -- far beyond the distance at which water ice sublimates -- it was already active, and researchers have concluded that its activity was driven by the sublimation of substances like carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and molecular oxygen and nitrogen.

Early images of Comet PANSTARRS. LEFT: Pre-discovery image taken by the 3.6-meter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea on May 12, 2013, when the comet's heliocentric distance was 23.7 AU. From the paper by Jewitt et al. (2017). RIGHT: Hubble Space Telescope image taken on June 27, 2017, when its heliocentric distance was 15.9 AU. Courtesy NASA.

Early images of Comet PANSTARRS. LEFT: Pre-discovery image taken by the 3.6-meter Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope on Mauna Kea on May 12, 2013, when the comet's heliocentric distance was 23.7 AU. From the paper by Jewitt et al. (2017). RIGHT: Hubble Space Telescope image taken on June 27, 2017, when its heliocentric distance was 15.9 AU. Courtesy NASA.

I took my first image of Comet PANSTARRS with the Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO) network on March 6, 2018, when its heliocentric distance was 14.40 AU, and have continued to take images on a semi-regular basis ever since then. I began making visual attempts in mid-June 2020 and continued these up through early November, but all these attempts were unsuccessful. After the comet's conjunction with the sun in mid-December I resumed visual attempts shortly after mid-February 2021, but these again were unsuccessful, up through March 11. Finally, on the morning of March 21, under excellent sky conditions I could clearly see the comet as a small and moderately condensed object of 14th magnitude. At that time it was located at a heliocentric distance of 6.81 AU, one of the largest distances at which I've ever detected an inbound long-period comet, and my observation came 638 days before perihelion passage, a new personal record for a pre-perihelion visual observation of an inbound long-period comet (beating my previous record-holder, Comet LINEAR C/2010 S1 (no. 494), by one week). Among all the comets on my tally, this is the 7th-earliest initial pre-perihelion detection of an inbound comet.

Images of Comet PANSTARRS I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: 10-minute exposure taken from McDonald Observatory in Texas on March 6, 2018, when the comet's heliocentric distance was 14.4 AU. It is the small diffuse object in the center. RIGHT: 5-minute exposure taken from Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands on March 21, 2021, seven hours before my first successful visual observation. The beginnings of a faint, broad tail extending towards the north-northwest (slightly to the right of straight up) can be seen.

Images of Comet PANSTARRS I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: 10-minute exposure taken from McDonald Observatory in Texas on March 6, 2018, when the comet's heliocentric distance was 14.4 AU. It is the small diffuse object in the center. RIGHT: 5-minute exposure taken from Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands on March 21, 2021, seven hours before my first successful visual observation. The beginnings of a faint, broad tail extending towards the north-northwest (slightly to the right of straight up) can be seen.

At this time Comet PANSTARRS is high in the morning sky, being located in western Lyra two degrees west of the bright star Vega. It is traveling almost due northward at a slow 5 arcminutes per day, and after passing through its stationary point at the end of March begins curving towards the northwest, crossing into Hercules in mid-May and reaching a peak northerly declination of +43.6 degrees in early June shortly before being at opposition just after the middle of that month. After that it begins curving back towards the southwest, passing through its other stationary point in early September and thereafter remaining accessible in the evening sky for another couple of months.

The comet is in conjunction with the sun -- 38 degrees north of it -- in mid-December, and becomes accessible again in the morning sky by sometime in January 2022, at which time it will be located in northern Ophiuchus some seven degrees east of the star Alpha Ophiuchi (Rasalhague). It will then be traveling in a generally eastward direction, although after passing through its stationary point in mid-April it curves westward and then southwestward, and will be at opposition just after mid-June (at which time it will be located a little over a degree east of the large bright star cluster IC 4665). The comet continues traveling southwestward, passing 20 arcminutes northwest of the globular star cluster M10 on July 15, crossing into northern Scorpius in early August, then traveling parallel to the stars in the "head" of that constellation (roughly one degree west of them) from late that month until close to mid-September, at which time it passes through its other stationary point. It continues traveling towards the south-southeast after that before disappearing into evening twilight around early November.

Beginning around the end of September, Comet PANSTARRS is inaccessible from the northern hemisphere for almost a full year. Initially, it is not especially well-placed for viewing from the southern hemisphere, either, although it enters southern circumpolar skies around mid-December. At the time of perihelion passage it is in conjunction with the sun -- 37 degrees south of it -- and located at a declination of -60 degrees in northwestern Pavo; from a physical perspective, it is on the far side of the sun from Earth at that time. It continues traveling towards the southeast, reaching a peak southerly declination of -70.8 degrees in late January 2023, and is closest to Earth -- a relatively distant 2.23 AU -- on February 14, when it will be located in Tucana approximately six degrees north of the Small Magellanic Cloud. Thereafter the comet travels northeastward through Hydrus, Horologium, Eridanus, and Lepus, before being in conjunction with the sun again -- 37 degrees south of it -- in mid-June. Throughout this time the comet's elongation never gets very high, reaching a maximum of 64 degrees in early March.

By sometime in August Comet PANSTARRS begins emerging into the morning sky, being located in southwestern Monoceros, and although still primarily a southern hemisphere object at that time, within about a month or so it becomes accessible again from the northern hemisphere as well. It passes through its stationary point shortly before the end of September and thereafter begins traveling slowly towards the west-northwest, crossing into Orion in mid-December a few days before it is at opposition -- at which time it will be located some four degrees east of the Great Orion Nebula M42. During the first few days of January 2024 it travels roughly parallel to the "belt" stars of Orion, some two degrees south of that prominent stellar pattern, and thereafter continues on until passing through its other stationary point in early March, when it will be located five degrees west of the star Gamma Orionis (Bellatix). From that point it heads towards the east-northeast before disappearing into evening twilight around the beginning of May. After conjunction with the sun in mid-June the comet again emerges into the morning sky around August and is opposition in mid-December, at which time it will be located in far northern Orion four degrees east of the star Zeta Tauri.

As is the case for almost all long-period comets, brightness forecasts for Comet PANSTARRS are quite problematical. Its visibility and relatively high brightness at such large heliocentric distances indicates that it is very bright intrinsically, and the high level of activity it has exhibited thus far suggests that it could be quite bright during the months around perihelion passage. On the other hand, orbital calculations indicate that it is likely a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, and more often than not such comets tend to underperform compared to initial expectations. Given all this, a cautiously optimistic scenario suggests that the comet may be around 13th magnitude when it is at opposition this coming June and perhaps 12th magnitude by the time it disappears into evening twilight late this year. When it appears in the morning sky in early 2022 it may be close to 11th magnitude, and it could brighten somewhat rapidly after that, reaching 9th magnitude and visibility in binoculars by March or April, perhaps 7th or 8th magnitude when at opposition in June, and possibly close to 6th magnitude, and flirting with naked-eye visibility, when it becomes inaccessible from the northern hemisphere and thereafter disappears into twilight.

Around the time of perihelion passage Comet PANSTARRS should be a naked-eye object, with a straightforward projection indicating a peak brightness of perhaps 5th magnitude. My observing experience suggests that it could be a magnitude or more brighter, or fainter, than this, and I consider it at least conceivable that it could reach 3rd magnitude, however I also consider it quite unlikely -- although not entirely out of the question -- that it could be brighter than this. The large distances from Earth and the sun and the relatively poor viewing geometry work against any kind of prominent display, although the fact that various images I've seen (including those I've taken via LCO) are already showing the development of a non-trivial tail suggests that there could be a decent display after all.

The comet may still be 10th or 11th magnitude when it becomes accessible again from the northern hemisphere during the latter half of 2023, and a magnitude or two fainter during the first few months of 2024. Conceivably, it may be perhaps 14th magnitude, and thus still visually detectable, when it emerges into the morning sky later that year, but even if that is the case it will likely fade beyond visual range within the subsequent few months.

It is truly unfortunate that a comet as intrinsically bright as this one is should remain as far from the sun and Earth as it does, and that the viewing geometry will be so unfavorable around the time of perihelion. Should one or more of these factors have been more favorable, it is entirely possible that Comet PANSTARRS could have become a "Great" comet; as it is, even at best it will likely put on a somewhat bright, but not especially prominent or conspicuous, show. Of course, for those of us in the northern hemisphere, things are even more unfortunate, since we miss out entirely on whatever show the comet does put on.

As I approach what may well be the twilight of my visual comet observing "career" -- something I will discuss more thoroughly in a near-term future entry -- I am glad that I have finally picked up Comet PANSTARRS, since I have considered it one of my pre-"retirement" "bucket list" comets. My intent right now is to follow it as long as I can, keeping in mind the one-year-long period when I will be unable to access it. At this time I have no plans or intentions of traveling to the southern hemisphere to observe it when it is around perihelion, although if it ends up surprising us and actually does become "Great" I suppose that such a trip is a possibility. Depending upon how my decision-making process unfolds and how long I am able to follow Comet PANSTARRS once it becomes accessible again in late 2023, it is within the realm of possibility that it may be one of the last comets -- conceivably even the last comet -- that I will ever see before I hang everything up for good.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 March 21.43 UT, m1 = 14.2, 0.6' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (February 13, 2022): I followed Comet PANSTARRS until late October 2021, by which time it had brightened to about magnitude 12 1/2 -- roughly half a magnitude fainter than predicted in the above scenario. After conjunction with the sun it began emerging into the morning sky in early 2022, although due to weather and other circumstances I did not observe it again until the morning of February 11; it appeared then as a relatively condensed object near magnitude 11 1/2 -- again, about half a magnitude fainter than the above prediction -- and it perhaps exhibited the barest hint of the northward-pointing tail that is apparent on CCD images I have seen of it.

At present the comet is located in northeastern Ophiuchus just over six degrees east-northeast of the star 72 Ophiuchi, and is traveling roughly due eastward at approximately 10 arcminutes per day. I describe its future path above, and accordingly I should be able to follow it for perhaps another seven months or so before it disappears into my southwestern evening twilight, and meanwhile we will have to see if it continues to run a half-magnitude fainter than the projections I've made. The comet will be closest to Earth (1.81 AU) in mid-July, at which time it will be located in central Ophiuchus less than one degree north of the globular star cluster M10 and presumably somewhere between 7th and 8th magnitude.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2022 February 11.51 UT, m1 = 11.7, 1.4' coma, DC = 6 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (September 15, 2023): It would be a fair statement that Comet PANSTARRS' overall performance was a significant disappointment. When it was nearest Earth in July 2022 it was only near 9th magnitude, and I was able to detect it very dimly in 10x50 binoculars on a handful of occasions (although telescopically it did exhibit a distinct broad tail 15 to 20 arcminutes long). It then faded by about a magnitude by the time it disappeared below my southwestern evening horizon in mid-September. According to reports from the southern hemisphere the comet reached a peak brightness near 8th magnitude when near perihelion in late 2022, but again had faded by about a magnitude by the time it disappeared into sunlight a few months later.

Observers in the southern hemisphere were reporting Comet PANSTARRS as being around 13th magnitude when it began emerging into the morning sky in August 2023. (Some images I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory network in mid-August did show it as being somewhat prominent, with a very faint, broad tail oriented roughly southward.) By September it was starting to become accessible to me again following its year-long absence from my skies, and this morning I successfully detected it; unfortunately, it was located right next to an 11th-magnitude star, and thus all I could really see was the inner coma, at roughly magnitude 13 1/2. I suspect that, overall, the comet is a bit brighter, and larger, than what I report below.

At this time the comet is traveling slowly eastward through rich Milky Way star fields in southern Monoceros, roughly three degrees west of the open star cluster M50 (and approximately nine degrees north of the bright star Sirius). It reaches its stationary point on September 25 and then begins traveling westward, and its motion through the next few months is described above. Obviously, it will be distinctly fainter than what I projected for this time.

With this morning's observation I have now been following Comet PANSTARRS for almost 2 1/2 years -- to be exact, 908 days -- which puts it in 13th place among all the comets in my tally, and in 5th place among the long-period comets. Given its faintness, I probably won't be following it for too much longer; I'd like to see it at least one more time so I can see it in a "clean" star field, but beyond that, I'll probably only observe it on a handful of additional occcasions, at most.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2023 September 15.47 UT, m1 = 13.7:, 0.7' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

700. COMET SONEAR C/2020 J1 Perihelion: 2021 April 18.56, q = 3.355 AU

51 years, two months, and one week after I saw my very first comet -- Comet Tago-Sato-Kosaka 1969g -- for the first time, I added my 700th comet to my lifetime tally. By an interesting coincidence, this event took place on the 50th anniversary of the occasion when, via a blundering schoolyard accident, I broke by lower right leg, fracturing my tibia into three separate pieces. Although not as serious as it could have been, this incident nevertheless had non-trivial effects on my future life, however at the same time partially in an attempt to ameliorate those effects it contributed to my maintaining the active physical lifestyle that I kept up until unrelated health issues forced me to curtail that within the relatively recent past.

The comet with which I mark this important milestone is, like quite a few other comets in my tally, a rather nondescript large-q long-period object that is and will remain quite faint. It was discovered on May 1, 2020 by Cristovao Jacques during the course of the Southern Observatory for Near-Earth Asteroids Research (SONEAR) program run by him and a few other amateur astronomers in Oliveira, Minas Gerais, Brazil; at that time it appeared essentially asteroidal and it was not immediately apparent that it was a comet, hence the name "SONEAR." When discovered Comet SONEAR was at a declination of -48 degrees and, traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 142 degrees), it spent the middle months of 2020 in southern circumpolar skies, reaching a peak southerly declination of -66.4 degrees when near opposition in late July. It started heading back northward after that, albeit remaining at moderately high southerly declinations, and after conjunction with the sun (20 degrees south of it) in mid-December it began emerging into the morning sky early this year. I began to take occasional images of it via the Las Cumbres Observatory network in mid-February, and in late March I began reading of visual observations from the southern hemisphere. By early April the comet had become accessible from my location (although it remains quite low in my southern sky), and on the morning of April 9 I successfully observed it as a small and moderately condensed object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude that exhibited distinct motion over an interval of half an hour.

At present Comet SONEAR is traveling through the "lower body"of the constellation Scorpius, being currently located at a declination of -38 degrees one degree northeast of the star pair Mu-1 and Mu-2 Scorpii, and traveling somewhat northward of due west at half a degree per day (and passing just over half a degree north of those stars on April 13). It passes through perihelion a week from now, and meanwhile over the next few weeks it gradually curves more northward, crossing into Libra at the beginning of May and being at opposition just after the middle of that month, when it will also be closest to Earth (2.37 AU on May 17) and crossing into southeastern Libra. Afterwards, the comet crosses into Virgo in mid-June and remains within that constellation for the next several months, passing six degrees east of the bright star Spica during the second week of July and going through its stationary point a month later; by sometime in September it will start disappearing into evening twilight. It might brighten by a few tenths of a magnitude by around the time it is at opposition, but will probably fade beyond the range of visual observations by another month or so thereafter.

Comet SONEAR is my 499th separate comet, which means that I now have only one more previously-unobserved comet to go before I reach my next significant milestone. I have hinted in quite a few previous entries about my future comet-observing activities, and will discuss those in more detail once I have reached by 500th separate comet; while I probably won't commit to any specific scenario and, to some extent, may make things up as I go along, at this point I consider it rather unlikely that I will ever get to lifetime comet no. 800. I suppose that could always change, of course . . .

Meanwhile, life here on Earth goes on. The worldwide global coronavirus pandemic has finally started to ease, and I received my second (of two) vaccination shots two weeks ago. On a more personal front, I have now become a biological grandfather for the first time: my grandson Ethan James Hale was born to my younger son Tyler and his partner Sara on March 25. He was somewhat premature and for the time being remains in the hospital, and thus I have not seen him yet; I would expect that that will change within the not-too-distant future. The circle of life continues . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 April 9.40 UT, m1 = 13.8, 0.3' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

.

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center