TALLY ENTRIES 701-710

I have now begun my eighth "century" of comets -- something which, in all honesty, I do not expect to complete. I do so with a pair of short-period comets that I have seen on previous returns, and thus for the time being my total of separate comets remains at 499; since the only comets that I have a realistic chance of adding to my tally within the short-term future are other short-period objects that I have seen before, barring a bright new discovery sometime soon it may be a few months before I am able to pick up my 500th separate comet.

This particular comet has a rather long and interesting history. It was initially discovered by the champion French comet hunter Jean Louis Pons in June 1819, and then followed for the next six weeks before disappearing into sunlight en route to a rather close approach to Earth (0.13 AU) shortly after mid-August. The German mathematician Johann Encke -- at that time engaged in orbital calculations of the comet that now bears his name -- calculated an orbital period of about 5.6 years for Pons' comet, but this orbit apparently was not sufficiently accurate to predict a future return, and it became lost. It was finally re-discovered as a new comet in March 1858 by the German astronomer Friedrich Winnecke, and very quickly thereafter the astronomers of that era recognized it as being identical to Pons' 1819 object.

Comet Pons-Winnecke has been recovered at most of its returns since then. With an orbital period that has remained within the general vicinity of 6 years (presently 6.3 years), it has undergone repeated close approaches to Jupiter which, over time, have acted to increase its perihelion distance, from around 0.78 AU at the time of Pons' and Winnecke's discoveries, to around 1.0 AU around the beginning of the 20th Century, to roughly 1.25 AU ever since the middle of the 20th Century. A rather remarkable series of returns took place during the 1920s and 1930s when it made several close approaches to Earth, including to 0.14 AU in June 1921 and to 0.11 AU in July 1939. The most dramatic approach took place on June 26, 1927, when the comet passed just 0.039 AU from Earth -- the second-closest confirmed cometary approach to Earth during the entire 20th Century -- and briefly became as bright as 4th magnitude with a 1-degree-wide coma that traveled southward at up to 11 degrees per day. This approach enabled the first serious attempts to determine the size of a cometary nucleus, with most investigations suggesting a diameter on the order of a few km -- close to the presently accepted value of 5.2 km.

These approaches also brought with them a meteor shower, the June Bootids, that produced strong displays -- up to several hundred meteors per hour -- in 1916, 1921, and 1927. Perturbations by Jupiter have now moved the June Bootid meteor stream away from Earth's orbit and there haven't been any strong displays since then -- with the exception of a brief outburst of over 100 meteors per hour that was witnessed from Japan, Europe, and Canada in 1998. Since the comet was 2 1/2 years past perihelion at the time and was no longer making close approaches to Earth, the cause of this particular shower remains somewhat of a mystery.

Following the comet's placement into something close to its present orbit following a somewhat distant approach to Jupiter (0.94 AU) in 1953, visual observations all but ceased for several returns, and essentially all the observations obtained of it were via short-exposure photographs taken for astrometric purposes. Since these tend to produce very faint brightness measurements, this led to a general speculation that Comet Pons-Winnecke had undergone a significant diminishing of its intrinsic brightness. In the early 1980s this conclusion was challenged by a Dutch amateur astronomer, Reinder Bouma, who pointed out that the viewing circumstances at the coming return in 1983 were favorable and that it might still be detectable visually.

Bouma's prediction, which was published in an Australian journal, was not widely circulated, but a few observers in Austalia succeeded in observing it at around 12th magnitude. I learned of this -- and was quite surprised -- when I arrived in Australia in mid-June for a visit to that country following the total solar eclipse that I had viewed from the Indonesian island of Java earlier that month, and by using a telescope owned by observing assistant Tom Cragg at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales successfully detected it near magnitude 12 1/2 (no. 59). I managed to obtain one additional observation, very low in the southeastern sky, after my return to the U.S. a week later.

I searched for Comet Pons-Winnecke a handful of times during the mediocre-geometry return in 1989 but failed to detect it, and did not attempt it during its unfavorble return in 1996. The next return, in 2002, was a relatively good one, with a minimun distance from Earth of 0.63 AU taking place in early June, and I successfully followed it for two months (no. 309) as it reached a peak brightness of 12th magnitude. The return in 2008 was another mediocre one although I did search for it a couple of times, unsuccessfully, and again I did not attempt it during the unfavorable return in 2015. On its present return the comet was recovered as long ago as January 7, 2020 by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona, as a very faint object close to 22nd magnitude. It was followed for a few weeks after that, and after conjunction with the sun last August has been under more-or-less continuous observation since late last year, although until recently it has remained an essentially inactive object. Only within the past few weeks has it started to show some activity, and I made one unsuccessful visual attempt for it in late April; during my first attempt of the current dark run, on the morning of May 9, I successfully detected it as a small and moderately condensed object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude.

.

LEFT: A set of five "stacked" CCD images (total exposure time 9 minutes) I took of Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke on June 13, 2002, during its return that year (no. 309). RIGHT: A 5-minute exposure of Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands on May 8, 2021, slightly over 24 hours before my first visual observation on the current return.

LEFT: A set of five "stacked" CCD images (total exposure time 9 minutes) I took of Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke on June 13, 2002, during its return that year (no. 309). RIGHT: A 5-minute exposure of Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands on May 8, 2021, slightly over 24 hours before my first visual observation on the current return.

It so happens that this year's return of Comet Pons-Winnecke is the best one it has made during my lifetime thus far, with a minimun distance from Earth of 0.44 AU taking place on June 12. It remains in the morning sky throughout most of its period of visual detectability, at present being located in eastern Aquila about one degree east of the star Theta Aquilae and traveling towards the east-southeast at slightly over one degree per day. It crosses into Aquarius shortly after the middle of May and remains within that constellation for the next few weeks (with the exception of the first week of June, when it crosses far northeastern Capricornus), and when closest to Earth it will be located some two degrees north of the star 41 Aquarii. Over time the comet turns more and more directly southward, crossing into northeastern Piscis Austrinus during the fourth week of June and passing 1 1/2 degrees northeast of the bright star Fomalhaut on June 25 before crossing into Sculptor a couple of days later (and passing 15 arcminutes northeast of the bright spiral galaxy IC 5332 on July 7) then into Phoenix (and dropping south of declination -40 degrees) in mid-July. It goes through its stationary point in early August and drops south of declination -50 degrees a week later, before reaching a peak southerly declination of -52 degrees at the end of that month and being at opposition shortly before mid-September. While the comet is heading in a generally northward direction at that time, it remains moderately deep in southern skies for quite some time thereafter, finally going back north of declination -40 degrees shortly before the end of October.

Although my evidence for this is somewhat spotty, my observations -- both successful and unsuccessful -- of Comet Pons-Winnecke during previous returns suggests it may exhibit an asymmetric brightness behavior similar to that of Comet 6P/d'Arrest (which returns later this year, incidentally), i.e., remaining faint and relatively inactive until shortly before perihelion, and then brightening almost explosively before diffusing out and fading away gradually; its brightness thus far during the present return seems to be consistent with this. If it indeed exhibits such a behavior, the comet should brighten rapidly over the next few weeks, reaching a peak brightness of 11th magnitude, perhaps even 10th, around the time it is nearest Earth in mid-June. As it fades I should be able to follow it until probably sometime in July, although its increasing southern declination will start to make observations a bit difficult before long; observers in the southern hemisphere should be able to follow it visually until at least August and possibly September.

After staying relatively far away from Jupiter for over half a century, Comet Pons-Winnecke finally encounters that planet again (at a distance of 0.65 AU) in September 2025, which will drop its perihelion distance down to 1.13 AU. Additional approaches to Jupiter in 2037 and 2049 will decrease its perihelion distance further to about 0.85 AU -- not much greater than that during its original discovery returns -- by the middle of the 21st Century. Despite this, even without considering the "retirement" from visual comet observing that I have been discussing off and on during previous tally entries, I will almost certainly not see this comet after this year's return, since the next three returns (in 2027, 2033, and 2039) all take place under geometry similar to that of the returns in 1989 and 2008. It makes approaches to Earth of 0.21 AU in July 2045 and 0.17 AU -- which takes place almost directly sunward of Earth -- in June 2062, but I will leave observations of those encounters to the comet observers of those eras.

Although the primary focus of my lifetime observational activities has been on comets, I have often observed other transient phenomena as well, including novae and supernovae, at least those that have been relatively bright. In the general slowdown in observational activity that I have been undergoing during the recent past I have not been expending much effort on such events, and, indeed, despite the fact that at least three relatively bright novae have appeared earlier this year I didn't observe any of them or have any plans to do so. However, a recent report announced that one of these novae, Nova Cassiopeiae 2021 (aka V1405 Cassiopeiae), which had been discovered on March 18 by Japanese amateur astronomer Yuji Nakamura -- one of the discoverers of Comet Cernis-Kiuchi-Nakamura 1990b (no. 139) and among those who independently re-discovered Comet 122P/de Vico P/1995 S1 (no. 204) -- and which had remained near 8th magnitude since then, had brightened dramatically within the recent past. On the morning that I added Comet Pons-Winnecke I observed this nova during dawn with 10x50 binoculars near magnitude 5 1/2, and on the following morning (when I added the below comet to my tally) I observed it in a darker sky with my naked eye at magnitude 5.3. This is the 42nd nova I have observed during my lifetime (although the first since 2018), and the 6th nova that I have seen with my naked eye.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 May 9.41 UT, m1 = 13.8, 0.5' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (June 5, 2021): More or less as I expected, Comet Pons-Winnecke brightened fairly rapidly after my initial observation, and was close to magnitude 12 1/2 during the latter part of May (including when I observed it during the lunar eclipse on May 26). Shortly after the beginning of June, however, according to various CCD-based reports the comet underwent a distinct outburst within its inner coma, and some CCD images thereafter (including this one) showed a strinking series of jets and hoods, surrounded by a larger outer coma -- an appearance reminiscent of Comet 156P/Russell-LINEAR (no. 686) when it was brightest during the latter part of last year.

This all happened while there was a bright moon in the morning sky, and furthermore a week-long period of rainy and cloudy weather here in New Mexico prevented me from making any visual observations of the comet. I finally had reasonably clear sky conditions on the morning of June 5, and was somewhat surprised to see that it was only about a half-magnitude brighter than it was when I had last seen it, during the late May eclipse. The bright jet-shaped inner coma so prominent on the CCD images is much more subtle visually, and primarily manifests itself by the fact that the surface brightness of the trailing, or westward, side of the coma is marginally brighter than the leading, or eastward, side. There appears to be a small, stellar condensation near the apex of this brighter region.

Whether or not the fainter-than-expected appearance of Comet Pons-Winnecke this morning is perhaps due to the outburst already subsiding is something I cannot determine at this time. In any event, in light of the general overall behavior I described above, and the fact that its closest approach to Earth is a week away, the comet may continue to brighten over the next couple of weeks, although at present I don't expect it to get any brighter than about 11th magnitude. The rapidly increasing southerly declination -- -32 degrees by the end of this month -- will start to make observations from my latitude somewhat problematical before too much longer.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 June 5.39 UT, m1 = 11.8, 2.6' coma, DC = 2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

702. COMET 15P/FINLAY Perihelion: 2021 July 13.47, q = 0.992 AU

One day after first picking up the above comet, I added this one to my tally. Like the previous comet, this is another one that I have seen on previous returns; after obtaining a single observation at a low elevation during the mediocre return in 2002 (no. 304), I observed it again in 2008 (no. 434) during the course of "Countdown," and I discuss its overall history in that entry. It remained at a fairly small elongation throughout its 2008 return, and over the next two months I obtained a handful of observations following my initial one; it never really got much brighter than it was during that first observation.

As I indicated in that "Countdown" entry, Comet Finlay returned again in late 2014 (perihelion in late December), and remained fairly low in the southwestern evening sky throughout its period of visibility. It was around magnitude 12 1/2, close to its expected brightness, when I first picked it up (no. 557) shortly before mid-December, however just over a week later it underwent a distinct outburst, and was around magnitude 9 1/2 according to my measurements. It faded slowly from this, but then, in mid-January 2015 -- three weeks after perihelion passage -- it underwent an even larger outburst, to around 8th magnitude; I could easily detect it with 10x50 binoculars, and it exhibited a distinct telescopic tail close to 15 arcminutes long. I subsequently followed it for the next two months as it slowly faded beyond visual range.

As the comet's 2021 return approached, I noticed that there weren't any reported recovery observations. Starting in mid-February 2021 I began taking occasional sets of images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network, but I was unable to detect any sign of the comet during my first few attempts. Finally, on April 10 I spotted it on three images taken via the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, and nine hours later I was able to obtain three additional images of it via the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. Despite distinct trailing of stars on the various images I was able to perform the requisite astrometry and submit this to the Minor Planet Center, and when this was later published, it turns out that these observations were the earliest ones to be reported. Although other observers reported positions as soon as the following day, mine were the first -- which means that, inasmuch as these things are noted, I receive credit for making the recovery!

The astrometry software measured an approximate brightness of 17th magnitude for the comet, which is consistent with what I estimated from an examination of the images. The comet was approximately three arcminutes east-northeast of its expected position, and orbital calculations from these images and other post-recovery measurements indicate that its perihelion passage is approximately 1 1/2 hours earlier than what had been predicted; this difference is likely due to the actions of non-gravitational forces.

My recovery images of Comet 15P/Finlay, obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network on April 10, 2021. LEFT: 5-minute exposure taken at 8:20 UT from the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The comet is the small "dot" near the center. RIGHT: A "stacked" set of three images (total exposure time 15 minutes) taken near 17:40 UT from the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

My recovery images of Comet 15P/Finlay, obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network on April 10, 2021. LEFT: 5-minute exposure taken at 8:20 UT from the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The comet is the small "dot" near the center. RIGHT: A "stacked" set of three images (total exposure time 15 minutes) taken near 17:40 UT from the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales.

I took a new set of images via the LCO facility at Siding Spring on May 9, and was surprised to see that the comet had brightened dramatically over the course of the previous month. Its appearance on the images inspired me to make a visual attempt the following morning, and despite the fact that it was rather low in my southeastern sky before dawn, I successfully detected it as a diffuse, moderately condensed object slightly brighter than magnitude 13 1/2.

At present Comet Finlay is located near an elongation of 70 degrees, in eastern Aquarius some three degrees northeast of the star Delta Aquarii, and traveling towards the east-northeast at slightly over one degree per day. Since the sun is also currently traveling towards the northeast, the comet will remain low in my eastern sky for the next several weeks, especially since its elongation decreases (to a minimum of 52 degrees near the end of July) and its motion accelerates, to a maximum of 75 arcminutes per day around the time it is nearest Earth (1.09 AU) in mid-June. During this time it travels through Cetus, Pisces, Aries, and Taurus, and at the time of perihelion passage it will be located some six degrees south-southwest of the Pleiades star cluster. The comet remains in Taurus before crossing into Gemini in mid-August; by that time it is north of the sun, thus offering better viewing geometry for the northern hemisphere, and will be traveling just northward of due east (at approximately 50 arcminutes per day) as it reaches its (temporary) maximum northerly declination of +27 degrees in early September. It eventually crosses into Cancer -- where it remains for the next several months -- just before the end of that month.

Under ordinary circumstances I would expect Comet Finlay to reach a peak brightness near 11th magnitude around the time of perihelion passage in July. However, in light of its behavior in 2014 and its rapid recent brightening, it is conceivable that it could become somewhat brighter than that (or, for that matter, fade away between now and then). We'll just have to keep an eye on it and see what it does . . . In any event, barring anything too unusual I expect to be able to follow it until perhaps September or thereabouts.

As is true for many of the other short-period comets that I am observing these days, this is likely the last return during which I will see Comet Finlay. The next return, in 2028 (perihelion early February), is a relatively unfavorable one slightly inferior to that of 2002, and while -- as noted in the comet's "Countdown" entry -- it makes a close approach to Earth (now calculated to be 0.19 AU) in August 2034 during the return after that, whether or not I am actively observing at any level at that time remains to be seen. I highly doubt I will be able to obtain observations during the very close approach to Earth -- now calculated to be 0.041 AU -- in October 2060.

Even though routine recoveries of expected periodic comets are no longer officially recognized, the fact that I was able to make the recovery of Comet Finlay this time around is nevertheless quite special to me. As I recount in the tally entry for Comet 37P/Forbes three years ago, I was able to make a visual recovery of that particular comet during its 1999 return (no. 262), but this recovery of P/Finlay is the first time that I have been able to supply precise positional information for such an event. As I probably continue to decrease my visual observing activities during the coming months and years I will likely increasingly become more active in imaging, and I am hoping to incorporate a significant educational component to this. It is well within the realm of possibility that I might attempt additional periodic comet recoveries in the future, and perhaps get educators and students involved in this particular effort.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 May 10.44 UT, m1 = 13.3, 0.8' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

703. COMET 4P/FAYE Perihelion: 2021 September 8.84, q = 1.619 AU

Another long-time friend reappears on my tally -- and, like most other recent such additions, quite likely for the last time. As its low periodic comet number indicates, it was one of the earliest-known short-period comets, being discovered in November 1843 by French astronomer Herve Faye from Paris Observatory. Around that time it was faintly visible to the unaided eye near 6th magnitude, this brightness perhaps being due to an outburst that conceivably could have been triggered by a moderately close approach to Jupiter 2 1/2 years earlier. Faye's comet was found to be traveling in an orbit with an approximate period of 7 1/2 years, and there have only been relatively minor fluctuations in its orbital period and perihelion distance since then. While it has never been as bright as it was on its discovery return, it has nevertheless been a moderately easy telescopic object during most of its subsequent returns, and except for the returns of 1903 and 1918 when it was badly placed for observation, it has been recovered on every return since its discovery. The current return is the 23rd during which it has been observed.

Comet Faye has been around with me ever since I first started following comets. It had a favorable return in late 1969, and although this was a little too early for me to attempt any observations, I nevertheless read about it in publications at the time. It returned again under somewhat mediocre geometric conditions in early 1977, and in significant part due to this being during my freshman, or "plebe," year at the U.S. Naval Academy I again didn't attempt any observations. The comet had another mediocre return in mid-1984 and I did successfully observe it then (no. 69); a most remarkable event occurred during this return when my friend and colleague Charles Morris made a visual recovery (at my suggestion), a very rare occurrence in this day and age. (It turned out that the comet had already been recovered at Palomar by Jim Gibson two weeks earlier, but this hadn't yet been announced, so Charles did receive credit for his recovery.) It remained low in the eastern morning sky during that return and never got brighter than about magnitude 12 1/2, and I obtained only a handful of observations of it.

Comet Faye had a very favorable return in late 1991, and I followed it (no. 163) for over six months as it reached a peak brightness of magnitude 9 1/2 and I could faintly detect it with 10x50 binoculars. The 1999 return was very unfavorable, but I nevertheless was able to obtain a single observation of it (no. 259) as a very faint object 4 1/2 months before perihelion passage. The following return, in 2006, was another very favorable one almost identical to that of 1991, although an approach to Jupiter during the interim had increased the perihelion distance somewhat and thus it didn't quite get as bright; I followed it for almost seven months (no. 393) and it reached 10th magnitude. The return in 2014 was very unfavorable, and although I attempted it on a few occasions, I never succeeded in observing it that time around.

An approach to Jupiter (0.63 AU) on my 60th birthday (March 7, 2018) decreased the perihelion distance by about 0.04 AU. On its present return it was recovered on March 26, 2021 by German astronomer Bernd Lutkenhoner with the Slooh Observatory facility at La Dehesa, Chile, at which time he reported it as being around 16th magnitude. Various reports I've read and images I've seen have indicated that it has brightened steadily since then, and a series of images I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory network on June 16 suggested it was bright enough to attempt visually. Two mornings later I successfully observed it as a small and somewhat condensed object near magnitude 13 1/2.

Although not quite as favorable as those of 1991 and 2006, this year's return is still a moderately good one. At present it is in the morning sky at an elongation of 64 degrees and located in eastern Pisces some three degrees south of the star Eta Piscium; it is traveling towards the east-northeast at 40 arcminutes per day, and over the next two months it crosses through Aries and Taurus (curving gradually more directly eastward) while passing some five degrees south of the Pleiades star cluster shortly before mid-August and through the northern extremities of the Hyades star cluster two weeks later -- at which time it is at its farthest north point (declination +19 degrees). Now traveling due eastward but gradually curving more towards the south, Comet Faye crosses into northeastern Orion in late September, into southwestern Gemini in mid-October, and then into Monoceros just before the end of that month. It passes through its stationary point during the latter part of November when it will be located some four degrees east-southeast of the star cluster NGC 2264; thereafter it reaches a minimum southerly declination of +7 degrees shortly after mid-December and begins traveling westward, and is at opposition just before the end of the month (and year) when it will be located two degrees north of the star cluster NGC 2244 and the Rosette Nebula (NGC 2237). The comet then begins traveling towards the northwest, crossing back into Orion just after mid-January 2022 and passing through its other stationary point at the beginning of February.

Comet Faye should continue brightening steadily as it approaches perihelion, and will probably reach a maximum brightness near 11th magnitude during September and October. It will likely have faded by perhaps a magnitude or so by the time it is nearest Earth (0.94 AU) in early December, and thereafter will probably fade more rapidly; I will likely lose it by late December or early January.

The comet's next return, in 2029 (perihelion early March) is unfavorable, while the return after that, in 2036 (perihelion early September) is essentially identical to this year's; as I've indicated in previous entries, however, I will likely be finished with visual comet observing well before then. After additional alternating between favorable and unfavorable returns, the comet passes 0.5 AU from Jupiter in 2076 which will drop its perihelion distance down to just over 1.5 AU, and set the stage for the closest approach it will have made to the Earth in several centuries -- 0.57 AU -- shortly after the beginning of the 22nd Century. I will leave observations of Comet Faye at all these future returns to observers of future generations.

Now that the coronavirus pandemic is receding, things are slowly starting to revert back to normal, although the new "normal" will likely be somewhat different from the old one. The Governor of New Mexico just announced a couple of days ago that our State will fully reopen on July 1, now less than two weeks away. On the home front, I met my grandson Ethan for the first time a month ago; being born several weeks premature he was still small for his age, but at least he is out of the hospital and is home now, and hopefully will grow into a healthy young man during the years to come.

One interesting recent personal event involves the "Ice and Stone 2020" program that I conducted throughout last year. While putting together the program two years ago, on June 6, 2019, I took some images of "my" asteroid, (4151) Alanhale, to utilize as an illustration of how asteroids move against a background star field. I showed two images, taken two hours apart, to my partner Vickie to see if she could spot the moving asteroid; she didn't . . . but, she managed to spot another asteroid (that I was unaware of) in the same star field! Some research showed that this was (75591) 2000 AN18, which had been discovered by the LINEAR program here in New Mexico in January 2000. In light of the rather interesting circumstances involved, and since in a sense Vickie had "re-discovered" this asteroid, I submitted a request to the IAU's Working Group on Small Body Nomenclature to have it named after her. The entire asteroid-naming process has undergone some delays in the recent past, and it took two years before things began to get back on track, but I was informed a month ago that my request would be approved; just a few days ago the WGSBN formally announced (among quite a few other asteroids' names) the naming of asteroid (75591) Stonemose. (I have the annotated images posted as a part of the I&S20 presentation on "Main Belt Asteroids;" Alanhale is indicated by the blue arrows, Stonemose by the yellow arrows.) The two asteroids are unrelated to each other and are traveling in different orbits, and it was only a coincidence that they happened to be passing by each other -- at different distances from Earth -- for a few hours right at the same time I was taking the images. Vickie and I, meanwhile, have been together for four years now, and I am hoping that that remains true for however long this life lasts.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 June 18.42 UT, m1 = 13.4, 0.5' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

704. COMET 67P/CHURYUMOV-GERASIMENKO Perihelion: 2021 November 2.06, q = 1.211 AU

For the fourth time in three months, a long-time friend reappears on my tally. In a sense, this one goes all the way back to the beginning of my lifetime efforts of comet observing, since an article about its discovery appeared in the December 1969 issue of Sky & Telescope, one of the first two issues of that magazine that I owned (and that was found and brought to my attention by my late friend Mark Bakke, whom I discuss in an earlier entry). I first observed the comet during its very favorable return in 1982 (no. 53), during which it reached 9th magnitude and was visible in binoculars, and after missing it during its unfavorable return in 1989 I successfully observed it again during its returns in 1996 (no. 206), 2002 (no. 315), and 2009 (no. 444). This last return came while I was conducting "Countdown," and I discuss some of the details of my association with the comet, as well as its overall history, within that entry.

Comet 67P has returned once during the interim, in 2015, and during that return it became the most scientifically studied comet in history due to ESA's Rosetta mission. Rosetta was launched in March 2004, and after three gravity-assist flybys of Earth and one of Mars, as well as two encounters of asteroids within the asteroid belt, arrived at the comet in August 2014 and went into orbit around it the following month. Rosetta spent the next two years intensely studying the comet as it approached and then receded from perihelion before successfully soft-landing upon the nucleus in September 2016. (I discuss Rosetta's overall mission and scientific findings in Comet 67P's "Ice and Stone 2020" "Comet of the Week" presentation.) From an observational perspective the comet's 2015 return was a rather mediocre one, but I successfully picked it up shortly after mid-July (no. 577) and followed it for almost six months; it reached a peak brightness near 12th magnitude.

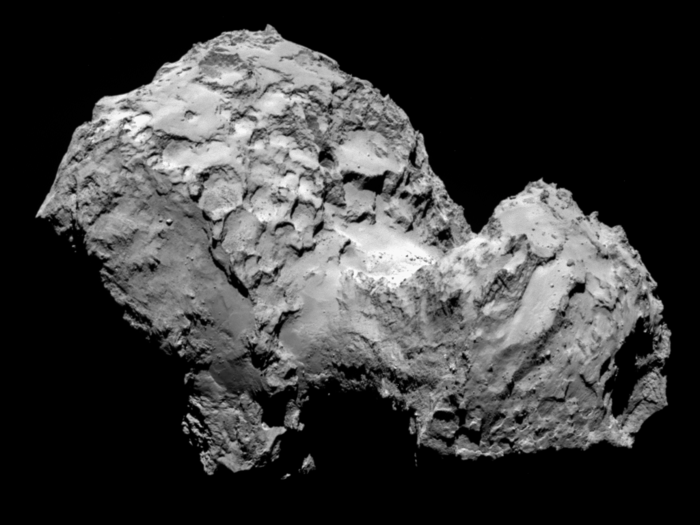

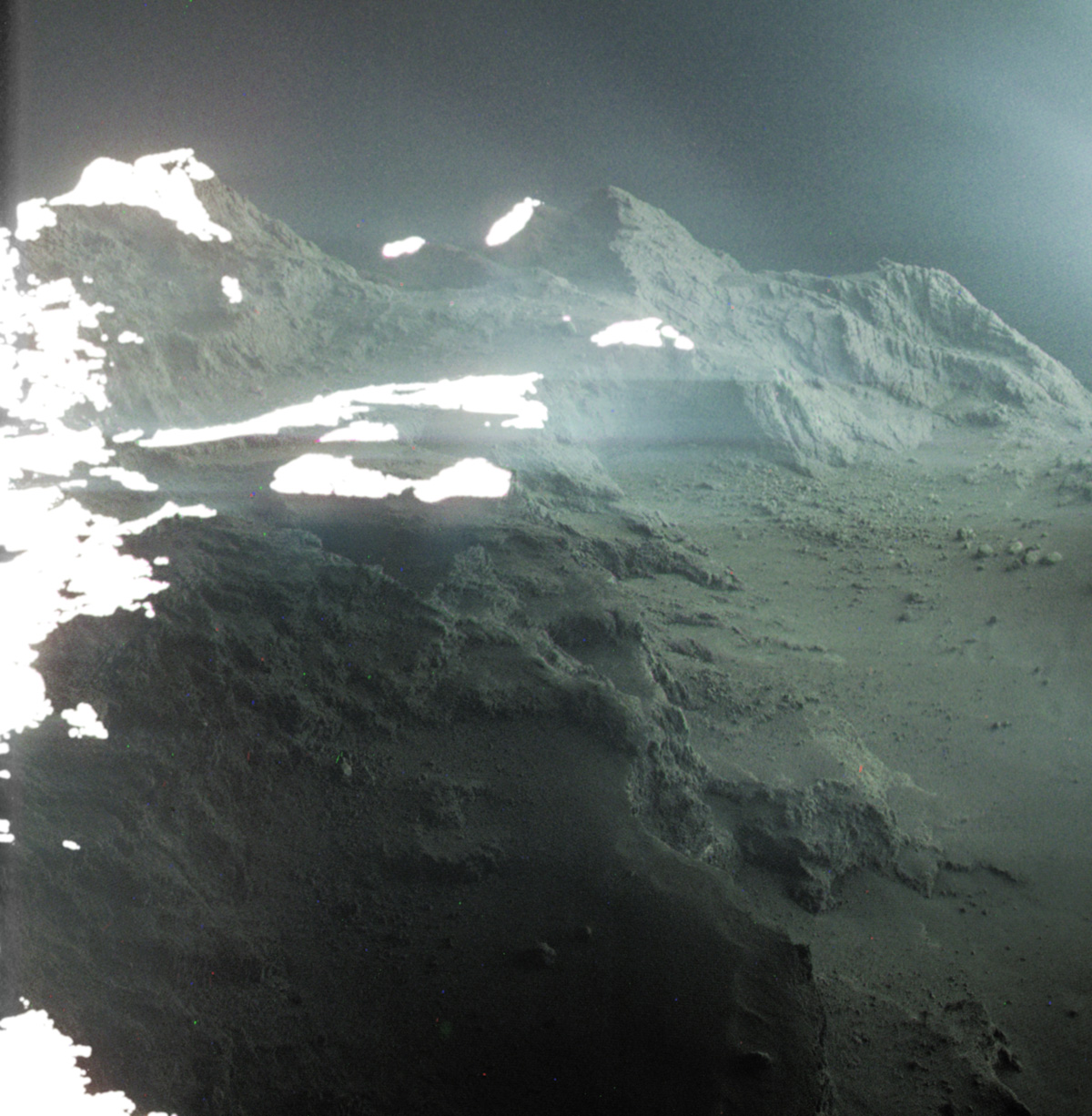

The nucleus of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as imaged by Rosetta. LEFT: The inactive nucleus, taken on August 3, 2014 during Rosetta's approach. RIGHT: Colorized and slightly processed image of the comet's surface, taken on September 22, 2014. Both images courtesy ESA/MPS for OSIRIS team/MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DADA/IDA, right image processed by Jacint Roger.

The nucleus of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as imaged by Rosetta. LEFT: The inactive nucleus, taken on August 3, 2014 during Rosetta's approach. RIGHT: Colorized and slightly processed image of the comet's surface, taken on September 22, 2014. Both images courtesy ESA/MPS for OSIRIS team/MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DADA/IDA, right image processed by Jacint Roger.

Comet 67P had been imaged by several large telescopes around the time of its aphelion in May 2012 prior to its 2015 return, and can thus be considered an "annual" comet and accordingly is not "recovered" in the traditional sense. The Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii imaged it in June 2018 prior to its aphelion in October of that year, but there were no further observations until it was imaged by Ukrainian astronomer Taras Prystavski on April 11, 2021, utilizing a remotely-controlled telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. It was about 19th magnitude at that time and has brightened steadily since then, and images I've seen over the past few weeks suggested it was now bright enough to attempt visually. A relatively heavy monsoon season this year here in New Mexico, combined with smoke in the atmosphere from the fires in California and elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, has made clear skies rather scarce lately, but under somewhat hazy but otherwise "clear" conditions I successfully observed the comet on my first attempt, on the morning of August 6; it appeared as a small and somewhat condensed object of 13th magnitude. This observation, incidentally, took place on the 7th anniversary of Rosetta's arrival at the comet.

While this year's return does not quite have the fanfare associated with it that the previous one did, it is, on the other hand, a very favorable one, similar to that of 1982 (the respective perihelion dates being ten days apart). The comet is presently located in southeastern Pisces and is traveling towards the east-northeast at roughly 40 arcminutes per day; over the coming weeks it travels through Cetus, Aries, Taurus (passing through the northwestern extremities of the Hyades star cluster in late September), and Gemini; at the time of perihelion it will be located six degrees west-southwest of the bright star Pollux and traveling almost due eastward. It then crosses into Cancer -- where it remains for the next six months -- just before mid-November, at which time it is closest to Earth (0.42 AU), and it passes through its stationary point in the northeastern part of that constellation during the third week of December. Now traveling towards the northwest, the comet passes through opposition shortly before the end of January 2022, at which time it is near its farthest north point (declination +29 degrees), and thereafter heads towards the southwest as it approaches and passes through its other stationary point in late February. It subsequently travels in a general east-southeasterly direction and eventually crosses into Leo in early May.

Historically, Comet 67P reaches its peak brightness one to two months after perihelion passage, and based upon that, and its behavior in 1982, it should be near 10th magnitude when near perihelion in November, and should reach a maximum brightness of 9th magnitude, and once again visibility in binoculars, during December. It should begin fading after that but should nevertheless remain visually detectable for at least the first two to three months of 2022.

As is true for so many other of the periodic comets that I am observing these days, this is quite likely the last return during which I will observe Comet 67P. The next return, in 2028 (perihelion early April), is unfavorable, and while the return after that, in 2034, is very similar to this year's -- indeed, the respective perihelion dates are identical -- as I've indicated in several previous entries it is distinctly unlikely that I will still be visually observing comets by that time.

I am thus rather glad that the viewing conditions are so favorable this time around. Due to that article in that long-ago issue of Sky & Telescope, in my mind I tend to associate this comet with the beginning of my comet observing "career," and while I'm not quite ready to hang things up yet, I am already beginning the slowdown in activity that will likely bring that "career" to its end within the not-too-distant future. This year's return would thus seem to be a fitting event with which to mark the beginning of the end of that "career." Perhaps even more fitting is the fact that, as Rosetta was approaching the comet, I was asked by a representative of the Rosetta team for my brightness data over the four returns during which I had observed it prior to that time, and I would like to think that the team found that data useful in their mission planning. While Rosetta (and its associated landing probe Philae) are well beyond the reach of any telescope here on Earth, in my mind's eye I can perhaps see them during the times I will be observing their final resting place, and can take some satisfaction in the knowledge that that "career" has continued to contribute to the collective knowledge of humanity.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 August 6.39 UT, m1 = 13.1, 0.9' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

705. COMET 6P/d'ARREST Perihelion: 2021 September 17.78, q = 1.355 AU

Over 4 1/2 months elapsed after I added my 499th separate comet to my tally before I finally observed my 500th (next entry). During the interim I added several "repeat" short-period comets, most of which date back in some way or other to my earliest days of comet observing. While I am not quite ready to hang things up for visual comet observing just yet, I have already started the slowdown in my observational activities that will likely lead to that outcome within the not-too-distant future, and it would seem that several of my long-time friends are coming by for one last visit before that time arrives.

This particular comet certainly fits that description. I have observed it previously in 1976 (no. 23), 1982 (no. 51), 1995 (no. 198), and 2008 (no. 435); this last return took place during "Countdown" and I discuss its overall history, as well as my own personal history with it, in its tally entry. Since then it returned in 2015, but the geometry was very unfavorable during that return and I did not attempt it; apparently some observers in the southern hemisphere were successful in obtaining a handful of visual observations then. As Comet P/d'Arrest can be considered an "annual" comet it is not "recovered" in the traditional sense; the earliest observations during the current return were made by American amateur astronomer John Maikner from his private observatory in Pennsylvania on March 10, 2021, although observations made five days later by Sergei Nazarov at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory's Nauchnij Station were the first to be reported. I made my first visual attempt for it on the evening of August 26, and successfully detected it as a faint and vague object slightly fainter than magnitude 13 1/2.

The comet already passed through opposition near the end of May and was closest to Earth (0.75 AU) just after the beginning of August, and remains visible in the evening sky throughout this apparition. It is presently located in eastern Ophiuchus some two degrees north of the star Eta Ophiuchi and is traveling towards the southeast at approximately 50 arcminutes per day (passing 1 1/4 degrees northeast of that star on September 3); it enters Sagittarius in mid-September and spends the next few weeks traversing the rich Milky Way star fields near the galactic center, passing directly over the Trifid Nebula (M20) on September 19. Over time the comet curves more directly eastward, and it reaches a maximum southerly declination of -31.8 degrees shortly before the end of October, at which time it crosses into northwestern Microscopium. From there it continues on a gradual curve towards the east-northeast, crossing into Piscis Austrinus shortly before mid-November, into southern Aquarius one month later, and finally into southwestern Cetus on the very last day of 2021.

Historically, Comet P/d'Arrest tends to remain faint and relatively inactive until just a few weeks before perihelion passage. After that point it brightens almost explosively and reaches a peak brightness three to four weeks after perihelion, after which it fades and diffuses out slowly over the subsequent weeks. It appears to be following that same basic pattern this time around, and accordingly I expect it to brighten quite rapidly over the next few weeks, to a peak brightness of perhaps 9th magnitude during October. It then should fade slowly (while growing larger and more diffuse) from that point on, and remain visually detectable until close to the end of this year.

I commented in this comet's "Countdown" entry that its mid- to late summer returns in 1976 and 1995 corresponded to some very dramatic upheavals in my personal life, and hinted that something similar might take place during that return in 2008. To some extent, that indeed did happen, as less than three weeks after I added it to my tally I was served with divorce papers (although the preliminary process had already begun by that time). It would take another year and a half for that process to fully play out, but it almost goes without saying that my divorce, together with all the events in its aftermath (including the move to my present residence), was a life-changing event.

I also commented that the comet's 1982 return came at a relatively quiet time in my life, and suggested that this year's return, which is very similar -- indeed, the respective perihelion times are only a little over three days apart -- might correspond to a similar period of relative quietness. That also seems to be true, for the most part, although life and its many associated events keep taking place. For example, Vickie's father, who moved in with us about a year and a half ago, celebrated his 90th birthday earlier this month, and several of his family members whom I had not yet met attended the party that we held. My younger son Tyler brought my grandson Ethan -- now five months old -- to the festivities, the first time that Ethan has visited my home. I continue to work on some educational efforts with Earthrise, and I continue to deal with the health issues that are contributing to my eventual "retirement" from visual comet observing, but -- unless something dramatic and unforeseen happens within the next few months -- life is indeed relatively quiet at the moment.

In any event, this year's return will almost certainly be the last time that I see this particular comet that has been a part of my life for such a long time. The next return, in 2028 (perihelion late March), is unfavorable, and while visual observations will likely be possible at the subsequent return in 2034 (perihelion early October), it will be fainter and less favorably placed than it is during this year's return, and I will likely have long retired from visual observing by then anyway. As I mentioned in its 2008 "Countdown" entry, P/d'Arrest has another mid- to late summer very favorable return in 2047 (perihelion end of July), but to reiterate the thought that I expressed there, I would be 89 years old then, and even if I'm still alive I don't even want to think about any "upheavals" my life might undergo at that time.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 August 27.13 UT, m1 = 13.7, 1.0' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

706. COMET PANSTARRS C/2020 PV6 Perihelion: 2021 September 26.00, q = 2.296 AU

Finally -- my 500th separate comet! The comet in question was discovered back on August 13, 2020 by the Pan-STARRS program in Hawaii; at that time it appeared as a stellar 21st-magnitude object, and despite being found to be traveling in an intermediate-period (approximate period 270 years) retrograde (inclination 128 degrees) cometary orbit it didn't exhibit any kind of cometary activity, and was accordingly announced under the asteroidal designation 2020 PV6. After conjunction with the sun in February 2021 it began emerging into the morning sky around April, and in mid-May Japanese amateur astronomer Hidetaka Sato reported that it was exhibiting a cometary tail in images he had taken. After seeing his report and images I took some images of it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network, which confirmed its cometary nature. Shortly before the end of May the Minor Planet Center announced its re-designation as a comet, and my reports were among those cited in support of that re-classification.

The comet went through opposition in mid-July, at which time it was also closest to Earth (1.67 AU). I made my first visual attempt in early June, however due in part to a heavy monsoon season this summer and to smoke from major fires in the western U.S., as well as the fact the comet was traveling though dense Milky Way star fields in Cygnus and Lyra, I didn't make any additional attempts for two months; meanwhile, however, various images I saw, including some additional LCO images I took, showed that it was brightening and developing a rather distinct tail. I was finally able to make an additional attempt in early August but didn't see anything, but when I attempted it again on the evening of August 28 I was able to detect it as a very faint and small object slightly fainter than 14th magnitude, that exhibited the expected motion during the half-hour that I followed it. I couldn't detect any sign of the tail visually, but that would have been beyond my range.

At present Comet PANSTARRS is located in southwestern Hercules and is traveling towards the southwest at just under half a degree per day. Over the next few weeks it slows down and curves more directly southward, and passes through its stationary point in late October, at which time it will be traversing the eastern regions of the Hercules Galaxy Cluster (Abell 2151). Its elongation from the sun is fairly small (43 degrees) at that time, however, and it will soon be lost in evening twilight as it approaches conjunction with the sun (37 degrees north of it) in mid-November. The comet is still almost a month away from perihelion passage at this writing but is receding from Earth, and unless there is a distinct asymmetry in its brightness behavior -- not unheard of with intermediate-period comets -- it is probably as bright now as it is going to get, and will likely fade beyond visual range before much longer. At most, then, I will probably only be getting one or two additional observations of it.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet PANSTARRS. Both images are 5-minute exposures taken with the one of the 40-cm telescopes at LCO’s facility at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. LEFT: May 19, 2021. This is one of the images that confirmed Hidetaka Sato’s report of cometary activity and that was cited in the announcement of the object’s re-classification as a comet. RIGHT: August 29, 2021, taken 2 1/2 hours after my first visual observation.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet PANSTARRS. Both images are 5-minute exposures taken with the one of the 40-cm telescopes at LCO’s facility at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. LEFT: May 19, 2021. This is one of the images that confirmed Hidetaka Sato’s report of cometary activity and that was cited in the announcement of the object’s re-classification as a comet. RIGHT: August 29, 2021, taken 2 1/2 hours after my first visual observation.

Since I have now reached the milestone of my 500th separate comet, what happens now? Four years ago, when I re-commenced these tally entries following my period of personal "dark time" in the mid-2010s, I speculated that, once I had reached this particular milesone (which I correctly predicted would be in the 2021-22 timeframe), I might start to slow down, towards a potential complete "retirement" after I had observed some particular comets expected in 2024. I wrote that a little over one year before the period of hospitalization that heralded the onset of the age-related health issues that, in all honesty, are making it more and more difficult for me to continue with the visual observing, and accordingly I believe that I will indeed start that slowdown; in fact, I have already begun doing so to some extent. I'm not entirely sure just what that "slowdown" will entail, and of course I reserve to myself the right to define it and modify my definitions as I see fit, but I will likely be limiting my observing sessions to no more than a handful per month -- indeed, I am already more-or-less doing so now. At the very least, I will probably not be trying to chase down every nondescript 14th-magnitude comet that comes along, although I will likely continue to follow the brighter and more notable comets that come by, including the various "old friends" that are in the sky right now and a few more that will be passing through over the next couple of years, as well as two recently-discovered potential naked-eye comets that will be passing through perihelion within the next several months. Once the 2024 comets have come and gone I may well hang things up for good, although I can always "come out of retirement" briefly if something especially bright and/or notable comes along.

Within the past two to three years I have become more active in imaging with the Las Cumbres Observatory network, and have had some successful investigative efforts with that endeavor; some of these are detailed in some of my tally entries, including this one. I expect to continue this and expand it, and to continue with related educational activities in general; I have been busy developing a specific project over the past few months and hope to make an announcement about this within the not-too-distant future. (I will also probably retool the Comet Resource Center to some extent in order to better reflect these changes in my focus.) As far as life itself is concerned, I am reasonably content, even though the various health issues are now keeping me from doing some of the things I have enjoyed doing throughout my life. Vickie has become and remains a very good partner for me, both of my sons are doing well, and I now have a young grandson whose life I hope to be a part of for at least some years left to come. I don't know how much longer of a future I have, but as I've written before, I'll continue to take each day as it comes.

And I continue to enjoy looking at the nighttime sky, and I retain and treasure the worldview, and the outlook on life, that that lifelong fascination with and study of the surrounding universe has given me. As for the comet observing, well, I've always known in the back of my mind that someday there would be a final comet I would observe, and a final observation I would make. I can't say when those might happen, but I believe I can say that they haven't happened quite yet.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 August 29.15 UT, m1 = 14.3, 0.3' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

707. COMET LEONARD C/2021 A1 Perihelion: 2022 January 3.30, q = 0.615 AU

As I indicated in the previous entry, having achieved the milestone of my 500th separate visually observed comet, I have begun a slowdown in my visual comet observing. Indeed, just a couple of weeks ago I formally announced my "semi-retirement" from that endeavor. But, as I indicated both above and in my announcement, "semi-retirement" does not mean that I am completely stopping; rather, it means that -- at least, for the next three years or so -- I am distinctly decreasing the frequency of my observing sessions and, for the most part, am restricting my activities to the brighter and/or more interesting comets.

And it would appear that I have a potentially bright and interesting comet here. It was discovered on January 3, 2021 -- exactly one year before perhelion pasage -- by Greg Leonard with the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona, at which time it was reported as being about 19th magnitude and exhibiting a short tail. Shortly thereafter, pre-discovery images extending to as far back as April 2020 were identified in data taken from Mount Lemmon as well as with the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii, and together this data all showed that the comet is traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 133 degrees) and appears not to be a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, although the previous return would have taken place approximately 80,000 years ago. These calculations also indicated the potential for a somewhat bright display, including possible naked-eye visibility, near the end of 2021.

I began taking images of Comet Leonard with the Las Cumbres Observatory network in early March, and continued to do so on an occasional basis up through late June. These images, as well as those taken by other observers, showed the presence of a relatively distinct tail, but while the comet did brighten somewhat during that interval, it did so at a slower rate than expected, which suggested that perhaps it would not become as bright as the inital projections indicated. After being in conjunction with the sun (34 degrees north of it) in early September, it began emerging into the morning sky, and images taken by several observers started to show that it was indeed brightening more in line with the earlier projections and that the tail -- clearly a dust tail -- was becoming more and more developed. Unfortunately, due to its low altitude and to the fact that I have trees in that direction from my observing site, I was unable to look for the comet for a while, but finally, on the morning of October 4, after it had climbed above the trees in early twilight I successfully detected it as a dim and somewhat condensed object of magnitude 13 1/2.

At present Comet Leonard is on the far side of the sun from Earth, but as it approaches perihelion it gradually swings over to our side of the sun and eventually passes between the sun and Earth. It is currently located in southwestern Ursa Major and is traveling slowly towards the east-southeast, for the time being remaining in the morning sky; it crosses into Canes Venatici shortly before mid-November and reaches a maximum elongation of 71 degrees shortly before the end of that month. After that it begins traveling more and more rapidly -- passing less than 4 arcminutes southwest of the center of the globular star cluster M3 on December 3 -- and within a few days enters back into morning twilight. The comet passes 0.23 AU from Earth on December 12, at which time it will be traveling 10 degrees per day, and passes through inferior conjunction (17 degrees north of the sun) a day later, and reaches a minimum elongation of just under 15 degrees one day after that.

Afterwards, Comet Leonard emerges into the evening sky, and passes just 0.028 AU from Venus on December 18 (being located 5 degrees to Venus' south-southwest at the time). It is already south of the sun by then and afterwards continues its general east-southeastward motion for the next couple of weeks as it pulls away from Earth, reaching a maximum elongation of just under 40 degrees in the final days of December. It passes through a stationary point a week after perihelion passage, and -- once again on the far side of the sun from Earth -- thereafter travels in a general west-southwesterly direction, passing through conjunction with the sun (22 degrees south of it) shortly before mid-February. It begins emerging into the morning sky by around March and is at opposition shortly before mid-June.

As I mentioned above, there is a potential for a decently bright display from Comet Leonard late this year, although as is always the case for newly-discovered long-period comets brightness predictions can be problematical. The comet's apparent recent increase in activity is a positive sign, as is the likelihood that it is not a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud, and a reasonably realistic brightening scenario suggests that it could be near 11th magnitude around the end of October, near 7th magnitude around the end of November, and perhaps as bright as 4th magnitude when it is nearest Earth around mid-December. The comet's small elongation, and location near conjunction with the sun, will likely make it a difficult object to observe around that time, unfortunately.

There is, however, another factor to consider. When Comet Leonard is in conjunction with the sun in mid-December, it will be located at the unusually high phase angle of 160 degrees. If the coma and tail contain significant amounts of dust, there is a distinct possibility of a temporary brightness increase, perhaps by as much as one to two magnitudes, due to forward scattering of sunlight. It does appear at this time that the comet is developing a non-trivial dust tail, so it is well within the realm of possibility that such a brightness enhancement could occur, and furthermore the geometry is at least somewhat favorable for a long apparent tail. The situation, in fact, is somewhat reminiscent of the circumstances we encountered with Comet McNaught C/2006 P1 (no. 395) as it approached its perihelion passage in early 2007, although I do not expect Comet Leonard to become anywhere near as bright as that object became. Due to the viewing geometry, observers at high northerly latitudes would get the best show, since they have a longer interval between sunset and comet-set.

The comet will briefly be visible in the evening sky from the northern hemisphere after conjunction, but after its approach to Venus visibility will be restricted to the southern hemisphere. It will likely begin fading, slowly at first as it is still approaching perihelion, but then more rapidly after that; a reasonable projection might suggest it will be perhaps 6th magnitude during early- to mid-January and 7th to 8th magnitude near the end of that month. The comet may be somewhere between 10th and 11th magnitude when it emerges into the morning sky in March, and perhaps still visually detectable near 13th or 14th magnitude as it approaches opposition in June; since it will be near a declination of -36 degrees around that time it would be accessible from the northern hemisphere again, albeit low in the southern sky.

It appears, in any event, that I have a potentially bright comet to mark the beginning of my "semi-retirement" from visual comet observing. This is actually the first of several known comets, both expected and newly-discovered, that have the potential to flirt with, and perhaps achieve, naked-eye brightness over the next three years, so provided that my health permits it, it looks like I will be keeping busy. As I've previously written, I may well "retire" for good once these objects have come and gone, but, we'll see what things are like when that time gets here.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 October 4.49 UT, m1 = 13.3, 0.9' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (December 2, 2021): Comet Leonard has brightened rather nicely since I first picked it up two months ago, and when I saw it yesterday morning I could easily detect it in 10x50 binoculars as a 7th-magnitude object with a half-degree-long tail. It will now start to sink fairly rapidly towards the eastern horizon, and it will only remain visible for another week or so before it disappears into the dawn. As recounted above, by the latter part of this month it becomes accessible in the evening sky during (and, later, after) dusk, potentially as a naked-eye object.

There has been some recent evidence, however, that suggests the comet may be in the act of disintegrating. My observation yesterday can be consistent with either a "yes" or a "no" to this possibility; the brightness is more-or-less where it should be, but on the other hand telescopically the coma did not clearly exhibit a central condensation but only a bright and somewhat "dense" central region; during the clearest moments I did seem to see a very faint and small star-like "condensation" of sorts. In my opinion, it is premature at this point to say anything definitive one way or the other, and only additional observations over the coming days will be able to determine just what is going on. It appears conceivable, at least, that the bright display that we had been hoping for later this month won't take place after all.

Yesterday's observation of Comet Leonard enabled me to achieve another milestone in my overall comet observing "career:" I have now managed to obtain at least one comet observation every calendar month for 40 consecutive years, i.e., going back to 1982. (The last calendar month during which I failed to observe a comet was September 1981.) At that time my experience as an observer, the equipment and information I had available to me, and our overall knowledge of comet activity in the inner solar system, were all drastically diffferent from what they are now. As for how much longer I will be able to maintain this "string," well, we'll see, but in all honesty I don't expect it to last for too much longer.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 December 1.46 UT, m1 = 6.9, 10' coma, DC = 3-4, tail 30' long (10x50 binoculars)

UPDATE (December 22, 2021): To (partially) borrow a phrase, any reports of Comet Leonard's demise seem to have been, at the very least, premature. I was able to grab one additional observation in the morning sky, on the 8th, by which time it had brightened to 6th magnitude, after which it disappeared into conjunction with the sun. According to reports I've read, the comet underwent a distinct increase in brightness as it did so, which may have been at least partially due to forward scattering of sunlight although there is also evidence that it underwent a genuine outburst then. It reappeared in the evening sky shortly thereafter, with most reports indicating a brightness a bit brighter than 5th magnitude. I was able to see it on the evening of December 19, when I obtained the photograph at right; with the low altitude, twilight, and bright moonlight I didn't attempt to see it with my naked eye, but it was clearly visible in binoculars near 4th magnitude. Additional reports, including from the southern hemisphere where it was quickly becoming better placed for obser-

Theoretically, Comet Leonard remains accessible from my location for a few more days, although it is very low in the southwest, and with poor weather expected here throughout the near future it is quite likely that I have seen it for the last time. Observers in the southern hemisphere should be able to follow it rather easily for the next few weeks -- via the scenario described above -- but since it is now receding from Earth and will be at perihelion passage in less than two weeks it is -- barring any additional outbursts -- probably not going to become any brighter than it is now.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 December 20.05 UT, m1 = 4.2:, DC = 7 (10x50 binoculars)

708. COMET ATLAS P/2021 Q5 Perihelion: 2021 August 30.44, q = 1.235 AU

One of the elements of the "semi-retirement" from visual comet observing that I recently announced is that I would no longer try to chase down every very faint (i.e., 14th magnitude or thereabouts) and nondescript comet that comes along, contrary to what I've been doing for the past three decades or so. At first glance, this comet might appear to go against that element, but it actually is somewhat interesting, so I decided it might be worth at least one attempt. And, as it turns out, I was able to pick it up . . .

The comet was discovered on August 29, 2021 by the ATLAS program based in Hawaii. When I saw it listed on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page (PCCP) it appeared to be bright enough to be worth attempting to image with the Las Cumbres Observatory network, and two days later I successfully captured it on some images I took with one of the LCO telescopes at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands; these showed the comet as a relatively faint 17th-magnitude object with a short westward-pointing tail. I performed the astrometry on these images and submitted it to the MPC, and when the discovery announcement was issued a little less than a week later it included my astrometry as well as the physical description I had submitted of the comet.

This new Comet ATLAS has been found to be a short-period object with an orbital period of slightly under six years. Since, at least when compared to most newly-discovered short-period comets being found these days, it is relatively bright intrinsically and has a fairly small perihelion distance, it seems a little strange that it hasn't been seen on previous returns. However, calculations soon started to show that it had passed very close (0.04 AU) to Jupiter in early 2019, and prior to that had been in a significantly larger orbit; although it's still a little early to know its exact pre-encounter history, the best calculations at this point suggest an orbital period near 11.5 years and a perihelion distance around 3.2 AU. Interestingly, in 2030 the comet will again pass very close to Jupiter (0.03 AU), and this will kick it back out into another larger orbit, with an approximate orbital period of 8.5 years and a perihelion distance near 2.3 AU.

It is not unusual for a comet that has been perturbed into a smaller orbit by Jupiter to become unusually bright on its first post-encounter perihelion passage, since it is receiving more heating from the sun than it has encountered in the past and thus its nucleus may be opening up active regions that were previously dormant. This appears to be what has been happening with Comet ATLAS; while it initially appeared to be far too dim to bother with any visual observation attempts, some scattered observational reports and some CCD images I've seen over the recent past have suggested that it might have become bright enough to be worth attempting, despite the fact that it is receding from perihelion. (On the other hand, the comet has remained near a constant distance from Earth of 1.50 AU ever since its discovery.) I took some additional LCO images in early October which suggested that the comet is indeed bright enough to attempt visually, and on the morning of October 10 I successfully detected it as a vague and diffuse 14th-magnitude object that I followed for a little over half an hour.

Comet ATLAS is currently located in southeastern Cancer near an elongation of 60 degrees, and is traveling towards the east-southeast at approximately 40 arcminutes per day. Over the next few weeks its travels through Sextans, Leo, and Crater, and will pass through its stationary point in early January 2022 and will be at opposition in early March. Although it will be coming closer to Earth during much of this time -- being closest, 1.29 AU, in early February -- I suspect it will likely begin fading now, and indeed it is entirely possible that my initial observation will be the only one I obtain of it. The comet should return under similar geometry in 2027, although I believe it will likely be quite a bit fainter then than it is now, and in any event I will likely no longer be doing any visual comet observing by that time.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 October 10.47 UT, m1 = 14.1, 0.9' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

709. COMET 57P/DU TOIT-NEUJMIN-DELPORTE Perihelion: 2021 October 17.41, q = 1.720 UT

As I transition into my period of "semi-retirement" there are several short-period comets, quite a few of which I have seen on previous returns, that I expect to observe over the next two to three years, especially those that are coming by under reasonably favorable viewing geometry. On the evening of October 25, 2021, I added the first two of these returning periodic comets to my tally, and, somewhat surprisingly, the first of these is a "repeat" comet that I had no expectation of observing this time around.

The comet in question was independently discovered three times over a one-month interval in July and August 1941, with the delay in communications created by World War II being responsible for the lack of word of these discoveries being disseminated to the wider astronomical world. The discoverers were Daniel du Toit from the Boyden Station of Harvard College Observatory in South Africa; Grigory Neujmin from the Simeis Observatory in Crimea in the then-Soviet Union; and Eugene Delporte from the Royal Observatory in Uccle, Belgium. Du Toit and Neujmin both discovered additional comets, including short-period ones that I have seen and some of which are discussed in previous entries on this site, but while this was the only comet discovered by Delporte, in 1936 he discovered the Apollo-type asteroid now known as (2101) Adonis, for which there is some physical and orbital evidence that suggests it could be an extinct or dormant comet. The comet passed slightly within 0.3 AU of Earth during its discovery return and reached a peak brightness near 9th magnitude.

Following that discovery return the comet was "lost" for the next several returns, a situation exacerbated by two close approaches to Jupiter that increased its perihelion distance from 1.3 AU to its present value of 1.7 AU. Finally, it was recovered in 1970 by Charles Kowal at Palomar Observatory in California, and it has been successfully recovered at most of its returns since then. The 1989 return was moderately favorable and I attempted it, unsuccessfully, a couple of times, but since the subsequent return, in 1996, was distinctly less favorable I had no plans to attempt it then. However, in late July of that year -- over 4 1/2 months after perihelion passage -- it underwent a dramatic outburst of several magnitudes, and I managed to obtain a couple of observations of it (no. 217) as an object fading from 12th to 13th magnitude.

The comet's subsequent return in 2002 was very favorable, and I observed it on a handful of occasions (no. 311) near 13th magnitude, indicating that -- not surprisingly -- it had undergone some intrinsic fading from its post-outburst 1996 brightness. About three weeks before perihelion, meanwhile, the NEAT program in California detected a 19th-magnitude "companion" comet accompanying the main one, and within the next few days 18 additional "companion" comets, down to 23rd magnitude and spread out along a line over 20 arcminutes long, were detected by astronomers at the University of Hawaii. An analysis by Zdenek Sekanina at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory suggests that, while the fragmentation history probably can't be accurately determined, the most likely scenario is that the main "companion" split from the primary in 1996 -- which would be consistent with the outburst the comet underwent during that return -- and that the additional, smaller "companions" split from either the primary component or this main "companion" more recently.

None of the "companion" comets have been seen on any subsequent returns. The primary comet itself returned under relatively poor geometry in 2008 and under mediocre geometry in 2015, and I didn't make any attempts for it either time. On the present return the earliest-reported recovery observations were made by Francois Kugel in Dauban, France on April 19, 2021, although observations by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii on April 17 and by John Maikner in Pennsylvania as early as March 20 were subsequently reported. The viewing geometry on this year's return is very similar to that in 1989 and I had no plans to look for the comet, and meanwhile it went through opposition in mid-May and was reported as being around 17th magnitude in early October. In mid-October, however -- just before perihelion passage -- several observers reported it as having undergone an outburst and as being close to 12th or 13th magnitude. Since this happened shortly before full moon I had to wait until the moon cleared from the evening sky before I could make a reasonable attempt for the comet, and when I was finally able to do so on the evening of the 25th I could clearly detect it as a small and moderately condensed object of 13th magnitude.

Comet 57P is currently somewhat low in the southwestern evening sky at an elongation near 60 degrees, being located in relatively dense Milky Way star fields slightly north of the "teapot" of Sagittarius (and in fact is currently located two degrees north-northeast of the bright globular star cluster M22) and is traveling almost due eastward at approximately 40 arcminutes per day. Since it is coming off an outburst it will likely fade and diffuse out over the coming few weeks, and it is uncertain just how much longer it will remain visually detectable; indeed, with my reduced observing schedule it is entirely possible that I won't be seeing it again.

We will probably have to wait for future returns to see if "companion" comets like those observed in 2002 are being produced by the current outburst activity. Unfortunately, the next return, in 2028 (perihelion early March), is quite unfavorable, and while the return after that, in 2034 (perihelion mid-July), is very favorable, any "companions" being produced now will likely have dissipated before then. In the meantime, while the comet has been in a relatively stable orbit for the past few decades, a pair of approaches to Jupiter during the mid-21st Century will bring its perihelion distance down to about 1.25 AU by the end of this Century. It is entirely possible, then, that this comet will continue to provide entertainment for future generations of comet astronomers during the coming decades.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2021 October 26.07 UT, m1 = 12.8, 0.9' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (December 2, 2021): In all honesty I expected this comet to be a "one-time wonder" on my tally, as I suspected it would fade away rather quickly from the outburst that enabled my initial observation in the first place. However, not only did the comet maintain its brightness afterwards, it apparently underwent a second outburst in mid-November. Earlier this week I successfully observed it again, and it appeared both slightly brighter and slightly larger than it did during that first observation.

Regardless of what happens from here on out, I am nevertheless almost certainly finished with this comet. It is already quite low in my southwestern sky after dusk -- present elongation 52 degrees -- and by the time it is accessible again after the coming full moon it will be too low to obtain any meaningful observations.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2021 November 29.05 UT, m1 = 12.4, 1.3' coma, DC = 4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

710. COMET 132P/HELIN-ROMAN-ALU 2 Perihelion: 2021 November 13.11, q = 1.692 AU

Less than an hour after I added the previous comet to my tally on the evening of October 25, 2021, I added this one. (This is the 38th time that I have added two or more comets to my tally during the same night.) Like the previous one, this is an expected short-period comet, however unlike the above one this is one I fully expected to attempt and, hopefully, observe. Also unlike the previous one, I have not seen this particular comet before, although I have unsuccessfully attempted it during a couple of previous returns.

The comet was the third of three discovered in October 1989 by the team of Eleanor Helin, Brian Roman, and Jeff Alu during the course of a photographic survey program for near-Earth asteroids being conducted by Helin utilizing the 46-cm (18-inch) Schmidt telescope at Palomar Observatory in California. The first one, Comet Helin-Roman-Alu 1989v, was a long-period comet that I followed for four months (no. 130) and that reached a peak brightness near magnitude 9 1/2, while the second one is a short-period comet now known as 117P/Helin-Roman-Alu 1 which I observed as a faint object of 14th magnitude during its returns in 2005 (no. 371) and in 2014 (no. 524). It returns again next year (perihelion early July) and in fact I attempted it unsuccessfully a couple of times earlier this year when it was near opposition; I may or may not look for it again around the time of perihelion passage (when it will also be near its next opposition).

This third comet was reported as being 16th magnitude (photographically) when discovered, which suggested it was bright enough to be worth visual attempts, however I unsuccessfully looked for it twice. It was found to have an orbital period of slightly over 8 years, and it returned in 1997 under very similar viewing geometry; I attempted it one time, unsuccessfully. The returns in 2006 and 2014 were distinctly less favorable and I never considered looking for it, however this year's return takes place under very favorable viewing geometry similar to that in 1989 and 1997. What makes this year's return interesting, however, is that the comet passed 0.33 AU from Jupiter in early 2017, which decreased its perihelion distance from 1.9 AU down to its present 1.7 AU (and also shortened the orbital period slightly, to 7.7 years). The distinctly smaller distances from the sun and Earth under which the comet would be appearing suggested that it would be worth new attempts.

Comet 132P was recovered on this year's return on June 12, 2021 by Francois Kugel from Dauban, France. It was a very faint object of 20th magnitude when recovered, but it has brightened steadily since then, and over the past month or so I have read various reports and seen several images that have all suggested that it had indeed become bright enough to be worth visual attempts. When I made my first attempt for it on the evening of October 25 I successfully detected it as a faint and somewhat condensed object of 13th magnitude.