TALLY ENTRIES 741-750

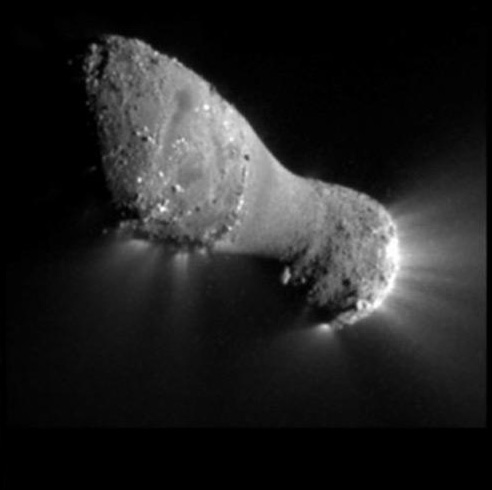

I am now entering the "home stretch" as I approach lifetime comet no. 750. I do so with the fourth member of the "Dependable Dozen" to be added to my tally, and that moreover is an old friend, having been discovered in 1986 by Malcolm Hartley at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales and that I have seen on three previous returns, most recently in 2010 (no. 477); I discuss its overall history, and my history with it, in the entry for that return. (Incidentally, this current return gives Hartley his 17th appearance in my lifetime tally, which puts him all alone in 7th place for most appearances in the tally.) The 2010 return was an exceptionally favorable one, during which the comet passed just 0.121 AU from Earth -- currently the 17th closest approach to Earth of all the comets in my tally -- and became faintly visible to the naked eye near magnitude 5 1/2 while displaying a large diffuse coma half a degree in diameter. Also during that return, it had a spacecraft visitor: the Deep Impact spacecraft, which had encountered Comet 9P/Tempel 1 in 2005 (no. 367) and later repurposed under the mission name EPOXI, passed 700 km from the nucleus on November 4 of that year. The EPOXI images revealed the nucleus as a peanut-shaped object some 2 km in length with significant jetting activity at both ends and a smooth, inactive plain between those ends.

Images of the nucleus of Comet 103P/Hartley 2 taken by the EPOXI mission on November 4, 2010 during the comet's return that year (no. 477). LEFT: The full nucleus, showing jetting activity at both ends and a smooth, inactive plain between those ends. RIGHT: The "snowstorm" image, a high-resolution view of jetting activity at one of the ends. Both images courtesy NASA.

Images of the nucleus of Comet 103P/Hartley 2 taken by the EPOXI mission on November 4, 2010 during the comet's return that year (no. 477). LEFT: The full nucleus, showing jetting activity at both ends and a smooth, inactive plain between those ends. RIGHT: The "snowstorm" image, a high-resolution view of jetting activity at one of the ends. Both images courtesy NASA.

After 2010 Comet Hartley 2 returned to perihelion in early 2017, under unfavorable viewing geometry; it was recovered as a faint object later that year and followed for several months. As the current return approached I attempted to recover it on a couple of occasions in late March 2023 with the telescopes of the Las Cumbres Observatory network but was unsuccessful; when it was later recovered on April 17 by Francois Kugel at his private observatory in Dauban, France it was clear that it had been too faint for me to have detected it. Following its recovery the comet brightened fairly rapidly, and LCO images I took in late July and early August suggested it was bright enough to attempt visually. On the late evening of August 10 I successfully detected it as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude that exhibited the expected motion during the half-hour that I followed it.

While not quite as good as that of 2010, the current return of Comet Hartley 2 is nevertheless a very favorable one, with a closest approach to Earth of 0.38 AU taking place on September 26. At present it is located in central Andromeda two degrees west of the star Beta Andromedae and is traveling towards the east-northeast at one degree per day (passing one degree north of that star on August 16). Gradually curving more directly eastward and accelerating, the comet enters Perseus and passes 20 arcminutes south of the open star cluster M34 on August 31, then reaches its peak northerly declination of +43 degrees six days later. As it begins a gradual turn southward it enters Auriga in mid-September, and at the time of closest approach to Earth will be two degrees south of the star Theta Aurigae and traveling at slightly over 1 1/2 degrees per day. At that time it should be at least as bright as 8th magnitude and quite possibly as bright as 7th magnitude.

Afterwards, the comet continues traveling towards the southeast -- curving more and more directly southward -- as it enters Gemini in early October, crosses southwestern Cancer late that month, and then enters western Hydra just before the month's end. It passes through its stationary point on December 5, when it will be located some six degrees west-southwest of the star Alpha Hydrae (Alphard); on January 1, 2024 it reaches its farthest south point (declination -14.6 degrees) and begins curving towards the northwest as it enters northeastern Puppis in mid-January and goes through opposition near the end of that month before entering Monoceros at the beginning of February. The comet should remain fairly bright throughout October but should fade afterwards, remaining visually detectable until probably sometime in January.

I should have a pretty good run of observations of Comet Hartley 2 this time around, but once the return is over, that will almost certainly be it for me as far as this long-time friend is concerned. The next return, in 2030 (perihelion early April), is very unfavorable, and while the return after that, in 2036 (perihelion late September, with a closest approach to Earth of 0.63 AU taking place early that month), is relatively good, as I have indicated numerous times in these pages I consider it very doubtful that I will still be observing comets then, even if I am still alive. I hope that my observations over these next few months can provide a fitting farewell as this friend and I prepare to go our separate ways.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 August 11.22 UT, m1 = 12.8, 1.5' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

742. COMET NISHIMURA C/2023 P1 Perihelion: 2023 September 17.64, q = 0.225 AU

During my early decades of comet observing, when many of the newly-discovered comets were being found by amateur astronomers who were deliberating hunting for them, it was common that a comet would be bright enough to be visually detectable as soon as it was discovered. With the advent of the comprehensive surveys a quarter-century ago most visually observable comets nowadays are being discovered many weeks, if not months, before they are bright enough to be seen visually, and it is quite rare for me to be able to observe a comet as soon as it is discovered. This particular comet is even more unusual in that not only was it visually observable at discovery, it was actually relatively bright.

The comet was discovered by a Japanese amateur astronomer, Hideo Nishimura, on DSLR images he had taken on August 12, 2023; he later found it on images he had taken the previous morning. This is Nishimura's third comet discovery: his first came almost three decades ago, in July 1994 with Comet Nakamura-Nishimura-Machholz 1994m (no. 189), which he found while visually hunting with large binoculars; it reached a peak brightness near magnitude 8 1/2 the following month while en route to passing 0.4 AU from Earth. His second discovery came just two years ago, with Comet C/2021 O1, which he found with the same DSLR and setup with which he found his current comet; that particular comet was a 10th-magnitude object in the morning sky at the small elongation of 23 degrees. The elongation decreased during the next few weeks and the comet soon disappeared into twilight as it approached perihelion, and I never had a decent opportunity to look for it.

When discovered, this newer Comet Nishimura was located in central Gemini 1 1/2 degrees south of the star Zeta Geminorum at an elongation of 34 degrees, and was reported as being about 10th magnitude. I was informed of it privately not too long thereafter, and soon it also appeared on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page, but unfortunately I was clouded out the following two mornings and was unable to observe it. The next morning -- the 15th -- also started out overcast, but after seeing the skies clear later on I began to set up the telescope for observations, only to watch the skies begin to cloud over again. I then noticed a small patch of clear sky traveling northward along the treeline to my east, and shortly thereafter the sky was clear in the comet's vicinity for approximately one minute. It took me about 30 seconds to locate the comet, and I had an additional 30 seconds to observe it before the clouds covered it back up. Despite the hurried observation the comet was quite easy to see as a moderately condensed object of 10th magnitude.

Calculations have revealed that Comet Nishimura is traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 130 degrees) and approached the inner solar system from behind the sun; indeed, it has been at an elongation of less than 40 degrees since late April. Only within the recent past has it emerged into the morning sky (although it may appear faintly in images taken by the Heliospheric Imager aboard the STEREO-A spacecraft in early July, and also in ultraviolet images taken by the Solar Wind ANisotropies (SWAN) telescope aboard the SOHO spacecraft in early August). It is currently traveling towards the east-northeast at approximately 50 arcminutes per day, and reaches a maximum elongation of just over 35 degrees around August 22, at which time it will be located some seven degrees south of the bright star Pollux and traveling at just over one degree per day. As its daily motion accelerates the elongation soon starts to decrease, dropping below 30 degrees on September 3 and below 25 degrees four days later. (Curiously, on August 27 it will pass less than 8 arcminutes south of Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 (no. 498), which has recently been detected in a state of outburst, although thus far it has been at too small of an elongation for me to observe.) Since the comet is approaching both the sun and Earth during this time it could, theoretically, brighten quite rapidly, and by the time it disappears into twilight it possibly may be as much as three or four magnitudes brighter than it is now.

The comet's unusually small perihelion distance suggests it could be a fairly bright object as it passes through perihelion, although its elongation will only be twelve degrees at that time and -- unless it is very bright -- it will be buried in twilight and almost certainly unobservable. It will be between Earth and the sun during this time and its phase angle will reach a maximum of 118 degrees on September 15, which suggests the possibility of brightness enhancement via forward scattering of sunlight; however, thus far it has not shown any indication of a dust tail -- just a weak ion tail on images I have seen -- so I am doubtful that such an enhancement will occur.

It is not at all certain that Comet Nishimura will survive its perihelion passage. If it does, it recedes from perihelion on the far side of the sun from Earth, with the elongation not going above 30 degrees until early November and not above 40 degrees until after the middle of that month; since it will be well south of the sun any observations would be restricted to the southern hemisphere. For what it's worth, the comet will enter southern circumpolar skies in early January 2024, but whatever might be left of it by then will almost certainly be very faint by that time. In all likelihood, then, any additional observations of Comet Nishimura that I am able to obtain within the next couple of weeks will wrap up its visibility as far as I am concerned.

When I first mentioned the "Dependable Dozen" a few entries back I noted that I only needed to add two additional comets not on that list to all but ensure I would reach comet no. 750 by the end of next year. With the addition of Comet Nishimura to my tally that has now happened. Thus, provided I am able to keep actively observing over the next 16 months and successfully observe the remaining eight comets of the "Dependable Dozen," I should easily achieve that remarkable milestone.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 August 15.45 UT, m1 = 10.2, 3' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (August 20, 2023): A revised (although probably still somewhat preliminary) orbit published earlier today places perihelion half a day earlier than the initial orbit and slightly increases the perihelion distance and inclination (to 133 degrees). (The appropriate updated infomation is now reflected in the header for this entry.) The general scenario described above remains basically unchanged, although the elongation now drops below 25 degrees on September 6, the maximum phase angle is now 122 degrees and will be reached on September 14, and the elongation at perihelion is now 13 degrees. (The closest approach to Comet 29P on August 27 is now just over 9 arcminutes.) This revised orbit also suggests the comet is traveling in an elliptical orbit with an approximate period of 300 years, although at this time it is still too early to attach much significance to this. If this is later found to be valid, this would suggest a higher probability that the comet will survive perihelion, and -- once a more precise orbital period is determined -- might help in identifying any previous returns in historical records.

I have now had some clear mornings, and had a successful observation of Comet Nishimura on August 19 (although the window between the comet's rising above the trees to my east and the onset of dawn is still fairly short). It appeared marginally brighter than it did during my initial observation.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2023 August 19.46 UT, m1 = 9.6, 3.5' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (September 6, 2023): Comet Nishimura has now been identified in images taken by the Pan-STARRS survey back in January 2023, and these have helped establish its orbital period as being close to 440 years. This would suggest that the previous return took place back in the late 16th Century, but thus far none of the records of comets that appeared around that time (nor, for that matter, around the times of earlier returns) can be convincingly identified as corresponding to this comet.

Meanwhile, the comet itself has brightened steadily as it has approached perihelion, although it is now rather rapidly sinking lower into the dawn sky. The weather around here has been quite good during the past few days, and after waiting for the recent full moon to dwindle a bit I observed the comet yesterday morning; although from my normal observing site it didn't rise above the trees until dawn was well underway, by motoring to a nearby site I easily detected it in 10x50 binoculars shortly after it rose above a nearby hill. In the binoculars it appeared as an almost starlike object of 6th magnitude, and I could see a suggestion of the ion tail that is quite prominent in recent images I have seen.

This will more than likely be my final observation of Comet Nishimura. Now traveling through the "head" of the constellation Leo, it is presently at an elongation of 25 degrees and is traveling just southward of due east at three degrees per day, and accordingly disappears into the dawn within the next couple of days. While, in theory, it should be accessible in the evening sky around the time of perihelion, as I mentioned above it will be at an elongation of only 13 degrees, so unless it becomes much brighter than expected it will be buried too deeply in twilight to be detectable. For what it's worth, the fact that it has been around before suggests a reasonable likelihood that it will survive perihelion passage this time around as well. On the other hand, thus far there has been no strong evidence of any dust tail, which in turn suggests a low dust content, and thus little likelihood of enhanced brightness due to forward scattering of sunlight.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2023 September 5.47 UT, m1 = 6.1, 4' coma, DC = 8 (10x50 binoculars)

743. COMET PANSTARRS C/2022 JK5 Perihelion: 2023 April 28.82, q = 2.687 AU

When I entered a state of "semi-retirement" from visual astronomical activities two years ago I didn't have a clear and specific definition of what that entailed, and in the time that has elapsed since then I have continued to be somewhat flexible in how I have approached that. One distinct element, however, is that I no longer try to chase down every faint, distant, nondescript comet that might be in the sky, although there have been a couple of comets that perhaps have challenged that. At first glace, this comet might appear to be another such comet, but there are enough intriguing elements to its story that I eventually felt it worthwhile to make an attempt for it.

The comet's story starts with its discovery as a 21st-magnitude stellar-appearing object on May 9, 2022 by the Pan-STARRS survey. A handful of additional observations were obtained over the subsequent three weeks, and in the absence of any additional observations or information it was assigned the asteroidal designation 2022 JK5. There the matter stood until April 3, 2023, when the ATLAS survey's telescope in Chile discovered an 18th-magnitude apparent comet. This object briefly appeared on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page but was removed once it was identified as being identical to the previously-discovered Pan-STARRS "asteroid." It was neverthless some two magnitudes brighter than the predictions based upon the previous year's observations, and several observers -- myself being among them -- noted its apparent cometary appearance on images. (In my case, images I took via the Las Cumbres Observatory's facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile on April 11 showed it as being somewhat diffuse compared to stars of similar brightness, although I really couldn't tell much else.) It was formally announced as a comet -- under the previously-assigned asteroidal designation -- on April 25; my astrometric measurements were included on the Minor Planet Center's discovery announcement, and my "cometary" observations were mentioned on that and on the discovery announcement issued by the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams.

Comet PANSTARRS in traveling in a shallowly-inclined (inclination 17 degrees) distinctly elliptical orbit with an approximate orbital period of 280 years. It was close to perihelion passage at the time its discovery was announced, but was still in the process of emerging into the morning sky then and has been approaching Earth ever since. Various images I have seen, including some LCO images I took in mid-July, have shown a distinct brightening since that time, and another set of LCO images I took on August 20 showed it as being bright enough to suggest it should be detectable visually. Early the following morning I successfully observed it, at 13th magnitude.

Images of Comet PANSTARRS I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: A "stacked" set of images I took on April 11, 2023, via the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The comet is the slightly diffuse object to the lower left of center. These images provided the evidence of cometary nature cited in the comet's discovery announcements. RIGHT: A single 3-minute exposure on August 20, 2023, taken via the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. I obtained my first visual observation slightly less than ten hours later.

Images of Comet PANSTARRS I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: A "stacked" set of images I took on April 11, 2023, via the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The comet is the slightly diffuse object to the lower left of center. These images provided the evidence of cometary nature cited in the comet's discovery announcements. RIGHT: A single 3-minute exposure on August 20, 2023, taken via the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. I obtained my first visual observation slightly less than ten hours later.

Now almost four months past perihelion passage, the comet is presently at its closest approach to Earth (2.01 AU) and will be at opposition shortly after mid-September. It is currently located in northern Sculptor some 2 1/2 degrees northeast of the star Delta Sculptoris and is traveling in a generally westerly direction at a relatively slow six arcminutes per day, and since it stays nears its present declination of -27 degrees for the next several weeks it remains fairly low in my southern sky throughout the near-term foreseeable future. I will probably look for the comet again in September once the upcoming full moon clears away from the evening sky, but I suspect it will probably begin fading, and it may well end up as a "one-time wonder." Regardless of whether or not I see it again, I am glad I was able to grab at least one observation of this visitor from the outer solar system.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 August 21.27 UT, m1 = 13.2, 1.4' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

744. COMET 2P/ENCKE Perihelion: 2023 October 22.53, q = 0.340 AU

"Hello, once more!" to one of the most famous of all comets, and which remains the comet with the shortest-known orbital period, at 3.3 years (although there are "active asteroids" with shorter orbital periods that I consider as "comets" for tally purposes). I discuss its overall history in its "Comet of the Week" presentation for "Ice and Stone 2020" and some of my own personal history with it in the tally entries for its returns in 2007 (no. 402), 2013 (no. 531), and its most recent previous return in 2020 (no. 683) -- this particular return was most unusual for me in that it is the only time that I have obtained post-perihelion observations of P/Encke from the northern hemisphere. The current return is the 65th during which it has been observed, and is the 14th return that I have personally observed. This is the 5th of the "Dependable Dozen" comets that I mentioned in a recent previous tally entry.

After its emergence into the morning sky following its conjunction with the sun earlier this year, I successfully obtained a couple of images of P/Encke on June 25 via the Las Cumbres Observatory network; it appeared as a very faint, essentially stellar object of 18th or 19th magnitude. By mid-August LCO images were beginning to show a very faint and vague coma, which was significantly more pronounced in additional images I obtained a week and a half later. I made a couple of unsuccessful visual attempts during late August; my failure to detect it lends support to some suspicions I've had that P/Encke has undergone some intrinsic fading during the recent past (although it's fair to note that the rich Milky Way star fields in Auriga that it was traveling through at the time didn't help in seeing it). After the full moon at the end of August I made my next attempt for P/Encke on the morning of September 7, and despite the Third-Quarter moon less than 25 degrees away I successfully detected it as a vague, marginally condensed object slightly brighter than 12th magnitude.

This year's return is a moderately favorable one for the northern hemisphere, and is almost identical to its return in 1990 (no. 145), this year's perihelion date being only six days earlier than that year's. At present P/Encke is located in northern Gemini some four degrees west-northwest of the star Castor and is traveling somewhat southward of due east at a little over 1 1/2 degrees per day; it passes 45 arcminutes north of that star on September 11. Over the next few weeks it curves more towards the southeast and accelerates, crossing into Cancer on September 15 and being closest to Earth (0.90 AU) on September 24, at which time it is traveling over two degrees per day as it crosses into Leo and makes a quick sojourn through the "head" of that constellation before traversing the "lion's body" and then crossing into Virgo on October 11. By that time it is rapidly disappearing into the dawn, with the elongation dropping below 30 degrees on October 7 and below 20 degrees eight days later. Historically, P/Encke tends to brighten quite rapidly as it approaches perihelion, and it should be close to 8th magnitude, conceivably even 7th magnitude, by the time it is lost in twilight. Realistically, I will probably only get, at most, three or four more observations of it before it's gone for me.

A little over three days after perihelion passage P/Encke enters the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO, and remains there for the next two weeks. Afterwards it stays at a small elongation, and in fact it re-enters the C3 field-of-view in early January 2024 and remains there for almost a month, although it will probably be far too faint to be detectable in C3 images. The comet finally emerges into the morning sky by the latter part of March but will almost certainly be a very faint object by that time.

I pointed out in the tally entry for its 2007 return that when I first saw P/Encke in late 1970 I was 12 years old, and was just starting out on my "career" of comet observing; it was only the fourth comet, and the first short-period one, that I ever observed, and this came just 9 1/2 months after my very first comet observation. I mentioned within that entry some of the interesting and important times in my life that happened to coincide with some of the various returns of P/Encke that I have observed; to that list I might add that it was while I was observing it during its return in 2017 (no. 610) that I met and began dating my current partner Vickie. And now, at age 65, I am observing P/Encke once again, and as before this return is coinciding with some interesting times in my life. I have recently obtained some rather important astronomical observations that I will mention in this space at the appropriate time, and I may be participating in some Earthrise-related endeavors within the near future that I will also mention if and when appropriate. On the personal side of things, in two weeks my younger son Tyler and his long-time partner Sara are getting married, and meanwhile my older son Zachary (presently residing in Australia) has recently informed me that he and his long-time partner Karina are expecting a child in February -- which will make me a biological grandfather for the second time. So, while Comet Encke continues to make its repeated passages through the inner solar system, life and other goings-on here on Earth continue for me, and for everyone else.

As for whether or not P/Encke and I will continue to check in on each other . . . Based upon the "retirement" timeframe of the end of 2024 that I have mentioned repeatedly in these pages, this would appear to be my final observed return of this comet. However, I have always maintained the caveat that, depending upon my health and other life circumstances, I could conceivably "come out of retirement" on occasion for bright or otherwise interesting comets. It so happens that P/Encke's next return, in 2027 (perihelion early February), is a rather favorable one, when it will be well placed in the evening sky. The comet's return in 2030 (perihelion early June) is impossibly placed for observation from the northern hemisphere, although observers in the southern hemisphere should get a good view of it as it passes 0.27 AU from Earth six weeks after perihelion passage. The return in 2033 (perihelion mid-September) is observable from the northern hemisphere but the viewing geometry is only mediocre, at best. The return after that, in 2037 (perihelion early January), is a very favorable one virtually identical to that first return of mine in 1970-71, the respective perihelion dates being only two days apart; the comet passes 0.38 AU from Earth in late 2036 and should be easily detectable in the evening sky. Whether or not I'll still be alive, and willing and able to "come out of retirement," at age 78 remains to be seen, of course, but if it were to come to pass it would seem to be a fitting bookend to this rather interesting "career" that I have had, and that Comet Encke has shared with me from almost the very beginning.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 September 7.41 UT, m1 = 11.7, 1.8' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 229x; moonlight)

745. COMET ATLAS C/2023 S2 Perihelion: 2023 October 15.38, q = 1.068 AU

Somewhat of a rarity in this day and age: a survey-discovered comet that is already bright enough for visual observations at the time of its discovery. The ATLAS program's telescope in Chile discovered this comet on September 28, 2023 -- right at the time of full moon -- and it was reported as being relatively bright. After being placed on the Minor Planet Center's NEO Confirmation Page (and then the Possible Comet Confirmation Page) numerous observers reported observations of it, and I was among these, obtaining two sets of observations via the Las Cumbres Observatory network (and which are included on the discovery announcement). After waiting for the Harvest Moon to clear from the evening sky and then a night of cloudy weather, I successfully detected the new comet on the evening of October 3 as a vague, diffuse object of 13th magnitude.

Comet ATLAS is traveling in a shallowly-inclined direct orbit (inclination 20.5 degrees). It has been accessible, and theoretically amenable to discovery, for quite some time now, being at opposition back in early April and high in the evening sky for the past few months. The fact that it wasn't picked up by any of the surveys -- and, at this writing, no pre-discovery observations have been reported -- suggests rather strongly that it underwent an outburst, or at least some significant brightening, shortly before it was discovered. This incident brings to mind a comet from a few years ago, Comet ASASSN C/2017 O1 (no. 626), which had similarly been accessible for some time before being discovered as a bright object that had recently undergone a rapid brightening. A recent report describes how images taken with the Hubble Space Telescope a few weeks after that comet's perihelion show a faint companion cometary object, suggesting that a fragmenting episode might have been responsible for that brightening. Perhaps something similar will be found with this comet.

In any event, at this time Comet ATLAS is in the evening sky near an elongation of 54 degrees, being located in western Ophiuchus some two degrees southeast of the star Epsilon Ophiuchi and traveling due eastward at one degree per day. Over the next few weeks it travels across Ophiuchus (passing half a degree south of the globular star cluster NGC 6366 on October 21), then in early November crosses Scutum and then Aquila as it begins curving somewhat northward before crossing into northern Aquarius near the end of that month, where it remains before crossing into Pisces just before the end of 2023. The comet is nearest Earth (1.20 AU) on November 6 and reaches a maximum elongation of 70 degrees in mid-December.

At this time it is difficult to predict what to expect in terms of Comet ATLAS' future brightness. If it has indeed undergone a recent outburst it may fade away pretty quickly and I will be obtaining very few additional observations of it. On the other hand, if the recent brightening is sustained the comet may remain visually detectable until sometime in November or even December. Time will tell . . .

There has been one significant event in my personal life lately: on September 23 my younger son Tyler and his long-time partner Sara were married. (Officiating the ceremony was Richard Kestner, whom a decade and a half ago I listed as a member of the "Earthrise Team" -- note that I am maintaining that page strictly for historical purposes.) My older son Zachary came from Australia for the wedding, and I was also able to visit with my former sister-in-law Alice Buck, who accompanied me on my first "science diplomacy" visit to Iran in 1999. Overall it was a happy and joyful occasion.

LEFT: Comet ATLAS on September 30, 2023, from the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. RIGHT: My younger son Tyler and my daughter-in-law Sara exchanging vows at their wedding on September 23, 2023. Richard Kestner is officiating. Photo by my partner Vickie Moseley.

LEFT: Comet ATLAS on September 30, 2023, from the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. RIGHT: My younger son Tyler and my daughter-in-law Sara exchanging vows at their wedding on September 23, 2023. Richard Kestner is officiating. Photo by my partner Vickie Moseley.

Comet ATLAS is the first comet I've added to my tally since Tyler's wedding. By a remarkable coincidence, this took place exactly 38 years after I added the first comet to my tally after my own wedding, Comet Hartley-Good 1985l (no. 86). At 7th magnitude, that was a significantly brighter comet than Comet ATLAS, and I ended up following it for four months, although it ended up taking somewhat of a back seat to Comet 1P/Halley 1982i (no. 85) which I was following extensively at the time as it approached perihelion in early 1986.

The interval of 38 years between my additions of Comets Hartley-Good and ATLAS corresponds to two Metonic cycles. By another interesting coincidence, on the exact night of the intervening Metonic cycle, i.e., on the evening of October 3, 2004, I also added a comet to my tally, Comet LINEAR C/2003 T4 (no. 357). Although it was relatively faint when I first saw it, Comet LINEAR eventually reached a peak brightness near magnitude 8.5 as it approached perihelion the following April, and probably would have become even brighter had it appeared under more favorable viewing geometry.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 October 4.09 UT, m1 = 12.8, 1.8' coma, DC = 1 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

746. COMET LEMMON C/2023 H2 Perihelion: 2023 October 29.19, q= 0.894 AU

I have now added half of the "Dependable Dozen" comets to my tally. Because of some "maybe" comets that I have successfully added, as well as some recent new discoveries, I am now well "ahead of the curve" as far as reaching comet no. 750 is concerned, and provided I am able to keep up my recent pace of observing I should easily reach that milestone within the not-too-decent future. Indeed, and especially if there are any more new discoveries that I am able to add to my tally within the next few weeks, I may even reach comet no. 750 by the end of this year.

This comet was discovered by the Mount Lemmon Survey in Arizona on April 23, 2023, at which time it was near opposition and appeared as a very faint and near-stellar object of 21st magnitude. It was found to be traveling in a rather steeply-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 114 degrees), and brightened very slowly over the next few months. Beginning around August it spent several weeks in near-conjunction with the sun, albeit some 40 degrees north of it, and only within the fairly recent past has it begun emerging into the morning sky. Various reports and images I have seen suggested the comet has become more active and has brightened rather significantly as it has emerged, and after waiting for the recent full moon to exit from the morning sky I successfully observed it (under some quite windy conditions) on the morning of October 12, at which time it was located in western Canes Venatici just one degree south-southwest of the bright spiral galaxy M106. It was easy to see as a diffuse, somewhat condensed object of magnitude 10 1/2.

Comet Lemmon will pass 0.193 AU from Earth on November 10, the 28th closest approach of all the comets on my tally (and the second-closest approach this year, after Comet 364P/PANSTARRS (no. 734)). It is traveling towards the east-northeast, presently at just under half a degree per day but rapidly increasing to almost two degrees per day on October 30 when it passes 45 arcminutes north of Eta Ursae Majoris (Alkaid, the star at the end of the "Big Dipper's handle"), at which time it is near its farthest north point (declination +50.2 degrees). About three days later it is in conjunction again with the sun (64 degrees north of it), after which it becomes primarily an evening-sky object and begins traveling towards the southeast through the constellation Hercules. The comet continues to accelerate as it nears Earth, and at the time of its closest approach will be located near the star 109 Herculis and traveling at almost 11 degrees per day. After that it begins to slow down but for a while it continues traveling southeastward quite rapidly through Aquila, Capricornus, Piscis Austrinus, and eventually Grus, which it enters during the final days of November and where it remains through the end of 2023.

I would expect Comet Lemmon to brighten at least somewhat rapidly over the next two to three weeks, and it may be close to 7th magnitude, possibly even 6th magnitude, at the time of its closest approach to Earth. Afterwards it will likely begin fading, but may remain detectable visually until sometime in December; its location then will make it primarily a southern hemisphere object. Once the moon starts entering the evening sky during the latter part of November I will likely be finished with it.

Comet Lemmon's orbit bears a fairly strong resemblance to that of Comet Suzuki-Saigusa-Mori 1975k (no. 17), although the difference in their respective orbital periods -- 450 years for that comet, vs. approximately 3800 years for Comet Lemmon -- rather strongly suggests that the resemblance in their orbits is just coincidence. Comet 1975k passed through perihelion at a similar time of the year as Comet Lemmon, and came even closer to Earth: 0.104 AU at the end of October 1975. This was the closest-approaching comet I had observed up until that time -- a status it would hold for the next 7 1/2 years -- and even now it is still the 15th-closest approaching comet of all the comets on my tally. Its appearance came during the fall semester of my Senior year of High School, and I obtained a handful of observations of it, with its reaching a peak brightness near 6th magnitude according to my measurements. As a part of my Science Fair project that year I borrowed a small spectroscope from the High School's Physics lab and held it to the eyepiece of the school district's 12.5-inch (32 cm) reflector to see if I could detect a visual spectrum of the comet; while I could see "something" near a wavelength of 4000 Angstroms the signal wasn't strong enough for me to identify anything conclusively.

My observations of Comet Lemmon and of the annular eclipse take place against a dark turn of events in the international arena, with the outbreak of war between Israel and the Hamas group in Palestinian Gaza. At this same time the war between Ukraine and Russia also grinds on, and there are disturbing events going on here in the U.S. as well. I suppose I am fortunate in that these various happenings do not affect me personally, but I am well aware that there are many of my fellow human beings who are not so fortunate. I really do feel helpless sometimes . . . The Earthrise mission, and my own personal career commitments, have been dedicated to trying to eradicate the hatred and the naked hunger for power that fuels these types of happenings, but it is clear that we, as a species, still have a long, long way to go.

I would like to believe that maybe, someday, humanity will finally learn, and grow up, and move beyond these urges and relegate them to the dustbin of history where they belong -- but I am becoming more and more convinced that, if that ever really does happen, it will be long after I am dead and gone.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 October 12.47 UT, m1 = 10.5, 4' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

747. COMET 62P/TSUCHINSHAN 1 Perihelion: 2023 December 25.11, q = 1.265 AU

As I continue to approach the milestone of my 750th visually observed comet, within the recent past I have achieved two other significant milestones. Although I didn't realize it at the time, when I added Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks (no. 740) on July 20 this turned out to be my 150th numbered periodic comet. (That comet, incidentally, has just undergone a large outburst that, at least for the time being, has made it bright enough to detect in 10x50 binoculars.) More recently, when I observed Comet Lemmon C/2023 H2 (no. 746) on the morning of October 20 that was my 8000th visual comet observation. (More or less as expected, that comet has been around 7th magnitude during the past week or so as it has made its passage by Earth, and at this writing it is the brightest comet in the nighttime sky.)

This newest comet -- the seventh of the "Dependable Dozen" that I have now observed -- was the first of two periodic comets discovered from Tsuchinshan, or Purple Mountain, Observatory in China in January 1965. I have observed it on four previous returns, the first of these being in 1984-85 (no. 80) and the most recent being the previous return in 2017 (no. 630); in that entry I discuss its overall history and my own personal history with it. During that return it reached a peak brightness near magnitude 10 1/2, somewhat brighter than what I had predicted.

I mentioned in the entry for Comet 62P's 2017 return that it would make a close approach to Jupiter in 2020, which would shorten its orbital period and decrease its perihelion distance and, moreover, bring it to perihelion this year under very

favorable geometrical conditions. From its present location in central Cancer it is traveling just southward of due east at close to one degree per day -- thus remaining, for the time being, primarily an early morning object -- crossing into Leo shortly before the end of November and into Virgo during the second week of January 2024 (and passing one degree north of the galaxy pair M65 and M66 on December 27). The comet subsequently remains in Virgo for the next eight months, being closest to Earth (0.50 AU) at the end of January, then passing through its first stationary point in mid-February, opposition shortly after mid-March, and then its other stationary point a month later; during some of this time it traverses across parts of the Virgo galaxy cluster. Based upon its brightness during previous returns, Comet 62P should reach a peak brightness of at least 9th magnitude during December and January, and may remain visually detectable until perhaps March or April.

The comet's next return, in 2030 (perihelion early March), is moderately favorable; it passes 0.86 AU from Earth and may reach a peak brightness of 10th or 11th magnitude. This is well after the "retirement" timeframe that I have often discussed in these pages, so at best there is a fair amount of uncertainty as to whether or not I'll see it again once the current return is over. In any event, however, this should not be the last time I encounter the name "Tsuchinshan," since one of the recent Purple Mountain discoveries, Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS C/2023 A3, has the potential to be a very bright object during the latter months of 2024. Indeed, it is entirely possible that that object will close out my visual comet observing "career."

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 November 15.37 UT, m1 = 10.8, 3' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

748. COMET 144P/KUSHIDA Perihelion: 2024 January 25.77, q = 1.399 AU

The eighth comet of the "Dependable Dozen" shows up on my tally, although I have to confess I was starting to wonder a little bit. This is a comet (current orbital period 7.5 years) that was originally discovered by Japanese amateur astronomer Yoshio Kushida in January 1994 and which I followed for two months (no. 184). I didn't look for it during the very unfavorable return in 2001, but saw it again, as a part of "Countdown," during its favorable return in 2008-09 (no. 443); I give more details about it and my personal history with it in its entry there. The comet became brighter than expected during that return, becoming visible in 10x50 binoculars and slightly brighter than 9th magnitude. Somewhat to my surprise, I was able to follow it for almost three months during the rather mediocre return in 2016 (no. 604), with its reaching a peak brightness near magnitude 11 1/2.

On its present return Comet Kushida was recovered on August 12, 2023 by amateur astronomer Francois Kugel in Dauban, France. Although he clearly reported it as a recovery at the time, there was some apparent confusion about the observations, as they were not fomally announced until a month later, under the designation of a supposedly newly-discovered "asteroid," 2023 PS2. In the meantime, additional observations, including some obtained the following day by Kugel as well as pre-recovery observations obtained in late June by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii, were announced under the regular designation of 144P. It took a while, but the confusion was eventually sorted out.

For quite some time after its recovery the comet remained relatively faint and inactive. I began taking images of it via the Las Cumbres Observatory network in early November, at which time it was only weakly active, although by the middle of that month I was detecting signs of a very faint outer coma. I made a couple of unsuccessful visual attempts in early December, and at the same time additional LCO images I took suggested that the outer coma was still quite faint. Finally, I visually detected the comet on the evening of December 14 as a very vague object of 13th magnitude, and was able to confirm this the following night; meanwhile, another set of LCO images I took between these two observations showed that the comet had distinctly brightened during the previous five days.

The geometry of Comet Kushida's current return is almost identical to that of 2008-09, the respective perihelion dates being only one day apart, and in fact its current perihelion distance is 0.04 AU less than it was then. It is thus somewhat surprising that it took so long for the comet to become bright enough for visual observations this time around, since in 2008 I first picked it up in mid-November near magnitude 12 1/2, and by the latter part of December it was already bright enough to detect in binoculars. Accordingly, it is difficult to know what to expect during the coming weeks, although the fact that it has brightened so rapidly during the recent past and that we are still over a month away from perihelion passage suggests that a peak brightness near 10th or 11th magnitude is a reasonable expectation, especially in light of its performance in 2016 (when all of my observations came after perihelion). For what it's worth, in 2009 I was able to follow it until late April.

Comet Kushida went through opposition in early November and through its stationary point early this month, and was closest to Earth (0.57 AU) just a few days ago. It is currently located in southeastern Aries just 20 arcminutes west of the star Sigma Arietis and is traveling towards the southeast at 10 arcminutes per day, although over the next few weeks it accelerates and curves more directly eastward and then eventually slightly northward of due east. It crosses into Taurus in mid-January 2024 and crosses the center of the Hyades star cluster during the second week of February (passing just seven arcminutes south of the bright star Aldebaran on February 10). Afterwards it crosses far northeastern Orion during early March before entering southern Gemini a week later, then passing 20 arcminutes north of the star Lambda Geminorum on April 4 and entering Cancer shortly after mid-April. The comet will likely fade beyond the range of visual observations sometime around then.

As I have written in the entries for several previous periodic comets, this will very probably be my last observed return of Comet Kushida, as I am now just over a year away from what I'm looking at as a likely "retirement" from visual observations (although in all honesty there remains a pretty big question mark in my mind as to exactly what happens after that). In any event, Comet Kushida's next return, in 2031 (perihelion early August), is distinctly unfavorable and I wouldn't be seeing it under almost any circumstances, and while the following return, in 2039 (perihelion early February), is relatively good, even if I'm still alive at the age of 80 I rather doubt I'll still be observing comets then. A somewhat close approach to Jupiter (0.43 AU) in 2044 will decrease the perihelion distance to near 1.3 AU and create conditions for some good returns afterward (especially in 2067-68), but any observations then will have to be made by whoever is observing comets at that time.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 December 15.26 UT, m1 = 13.1, 2.0' coma, DC = 1-2 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

749. COMET TSUCHINSHAN-ATLAS C/2023 A3 Perihelion: 2024 September 27.74, q = 0.391 AU

In my statement that accompanied my re-establishment of my tally entries back in mid-2017, I mentioned the possible scenario of "retiring" from visual comet hunting at some point in the future, something I have discussed numerous times in the entries I have posted since then. I hinted then of the year 2024 as the timeframe for such a "retirement," in large part due to the returns of the Halley-type comets 12P/Pons-Brooks and 13P/Olbers that year. At this writing, 2024 is now almost upon us, and, indeed, those comets are around: I picked up P/Pons-Brooks five months ago (no. 740) and it has been undergoing a series of outbursts ever since and currently is visible in 10x50 binoculars near 9th magnitude; P/Olbers, meanwhile, is presently around 17th magnitude and I hope to pick it up visually sometime within the next two to three months. In my mind, I had considered "retiring" once those two comets were no longer visually accessible to me, however the discovery of this particular comet -- now the ninth member of the "Dependable Dozen" to appear on my tally -- earlier this year has caused me to push back any such "retirement" until sometime around the end of 2024, at the earliest.

Back in late February 2023 I noticed that an object with an unusually high intrinsic brightness had been posted to the Minor Planet Center's Near-Earth Object Confirmation Page (NEOCP) and then shortly thereafter moved to the Possible Comet Confirmation Page; it had been discovered on February 22 by the ATLAS program's telescope in South Africa. As early as February 24 I began taking images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network and submitting the astrometry from these images to the MPC; by the time the object's discovery was announced on February 28 I had submitted five sets of astrometry from three different LCO sites, all of which were included on that announcement. The astrometry that had been submitted by me and other observers allowed the MPC to determine that the ATLAS-discovered object was identical to an object that had been discovered on January 9 by the Tsuchinshan ("Purple Mountain") Observatory in China, however only three positions from that single date were available, and even though the object had been placed on the NEOCP it was removed a couple of weeks later as being "not confirmed."

The object appeared completely stellar and near 18th magnitude on the various LCO images I took, and apparently also appeared stellar on images taken by most other observers. However, a couple of observers, mainly utilizing larger telescopes, did report detecting weak cometary activity, including in some pre-discovery images obtained in late December 2022 via the Zwicky Transient Facility program at Palomar Observatory in California. Additional pre-discovery images have since been identified in data taken with the Pan-STARRS survey in April, May, and June 2022 and in images taken with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile in early June 2022. All the data indicated that the object is a long-period comet traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 139 degrees); it was located at the rather large heliocentric distance of 7.7 AU at the time of its discovery from Purple Mountain (and 7.3 AU when re-discovered by ATLAS a month and a half later), and was still over a year and a half away from perihelion passage, when it would be located near Mercury's distance from the sun. This, combined with its apparent high intrinsic brightness, suggested that a potential very bright comet was on its way in to the inner solar system.

Ever since its discovery I continued to image Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS on a fairly regular basis via the LCO network. For the next few months it continued to maintain a stellar appearance, however by early June -- by which time it was about a month past opposition and had brightened to 16th magnitude -- it was starting to exhibit a slight diffuseness, which continued to grow more pronounced -- albeit slowly -- over the subsequent weeks. When I obtained my final pre-conjunction LCO observations in early September it had brightened further to near magnitude 15.5 and was exhibiting a short but distinctive stubby tail. Shortly thereafter the comet disappeared into twilight, and went through conjunction with the sun in late October.

The first reported post-conjunction observations of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS were obtained in late November, when its elongation was still under 30 degrees; these showed that it had brightened to almost 14th magnitude. After waiting for it to climb a bit higher in the sky, and after additional waiting due to moonlight and cloudy weather, I made my first visual attempt for the comet on the morning of December 18, and successfully detected it as a tiny and condensed but nevertheless slightly non-stellar object of 14th magnitude. On that same morning I successfully took images via the LCO network -- including a set from McDonald Observatory in Texas at the exact same time as my visual observation -- and the comet's appearance on these images was entirely consistent with what I saw visually; they also showed the short, stubby tail extending towards the north-northwest.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS. LEFT: September 3, 2023, from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. This is from the last set of images I obtained before the comet went into conjunction with the sun. RIGHT: December 18, 2023, from the LCO facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas. This was taken at the exact same time as my initial visual observation.

Las Cumbres Observatory images of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS. LEFT: September 3, 2023, from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. This is from the last set of images I obtained before the comet went into conjunction with the sun. RIGHT: December 18, 2023, from the LCO facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas. This was taken at the exact same time as my initial visual observation.

At this time the comet is still over nine months away from perihelion passage, and is located at a heliocentric distance of 4.4 AU. For the time being it is still somewhat low in my southeastern sky before dawn, at a present elongation of 45 degrees and located in northwestern Libra two degrees northwest of the star Delta Librae. It is currently traveling towards the east-southeast at a relatively slow 8 arcminutes per day, gradually slowing down and curving more directly eastward as it reaches its stationary point in early February 2024 when it will be located two degrees northwest of the star Beta Librae. After that it travels towards the west-northwest, gradually curving more directly westward and then eventually towards the west-southwest, being at opposition shortly after mid-April (when it will be located in central Virgo) then crossing into Leo in mid-June and into Sextans in early August. By that time it is getting low in the western sky after dusk, and it is in conjunction with the sun near the beginning of September.

Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS makes a brief appearance in the morning sky in late September, but reaches a maximum elongation of only 23 degrees on the 27th before beginning a plunge back into twilight. It passes almost directly between Earth and the sun on October 8, passing 3 1/2 degrees north of the sun and appearing at the unusually high phase angle of 173 degrees. (From October 7 until the 11th it will traverse the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO.) On the 12th the comet is nearest Earth (0.472 AU) and will be near an elongation of 15 degrees as it commences a rapid rise out of evening twilight, with the elongation increasing by almost five degrees each day until it reaches 40 degrees by October 19. It travels almost due eastward after that, reaching a maximum elongation of 56 degrees in early November when it will be located in northeastern Ophiuchus a couple of degrees northeast of the star 70 Ophiuchi. After that it travels towards the east-northeast through Serpens Cauda and Aquila as it sinks back towards the western horizon; it disappears into twilight in early January 2025 en route to another conjunction with the sun (28 degrees north of it) during the third week of that month; before doing so it passes 1 1/2 degrees south of the bright star Altair on January 11. For what it's worth, the comet begins emerging into the morning sky during the first half of February, when it will be located some five degrees east-northeast of Altair, and travels slowly towards the northeast before passing through its stationary point at the end of March and being at opposition in early July, when it will be located in southern Lyra.

There is no question that, given its relatively high intrinsic brightness, its small perihelion distance, and its relatively close approach to Earth, Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS has the potential to become a conspicuous naked-eye object, possibly even a "Great Comet," during the latter part of 2024. Of course, there can be a large difference between "potential" and "reality," and brightness predictions for long-period comets are always notoriously problematical. One perhaps significant detracting factor in this case is that Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS appears to be a "new" comet making its first visit into the inner solar system from the Oort Cloud, and in general such comets often tend to under-perform compared to expectations. (There have nevertheless been occasional exceptions to this from time to time.) One possible good indicator is that the comet was exhibiting a distinct tail in images when it was still 6 AU from the sun, which suggests it might possibly have a high dust content. Dust tail development in comets is usually strongest after perihelion, and with the viewing geometry around the time of its passage by Earth producing very high phase angles, and thus a reasonable possibility of some strong brightness enhancement due to forward scattering of sunlight, this would suggest the possibility of a very bright and long dust tail around mid-October (when the comet will be conveniently placed for viewing in the evening sky). Full moon, unfortunately, occurs on October 17, and this will detract from the overall show for a while, but if the comet maintains a reasonable brightness for two or three weeks we may still see something quite spectacular once the moon clears from the evening sky.

For the time being, about all we can do is see how Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS develops and brightens over the coming weeks and months. If it should reach visibility in binoculars by about mid-year and be flirting with naked-eye visibility by the time it starts sinking into the dusk during August, that could, potentially, by a good sign for a bright display later on. If the comet really does reach "Great Comet" status and realizes its full potential it could, theoretically, be better than the comet that bears my name (no. 199), and perhaps even better that what I consider to be the best comet I have ever seen, Comet West 1975n (no. 20). Meanwhile, if I really do decide to "retire" from visual comet observing at the end of 2024, and if Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS does indeed become a bright and spectacular object, then my "career" could go out with the proverbial "Bang!" Time will tell . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2023 December 18.51 UT, m1 = 14.1, 0.3' coma, DC = 8 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (June 3, 2024): After my initial visual observations of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS it brightened steadily over the subsequent months, and by the time it was near opposition in April 2024 it had reached 10th magnitude. It also began exhibiting a distinct dust tail, which is prominent in CCD images and easily seen visually, almost giving it the telescopic appearance of a miniature "Great Comet." Since that time, however, its brightening has stalled, with almost no change for the past six weeks or so; indeed, when I observed it last night it even appeared to have faded slightly, although within the "margin of error" of my previous measurements. As our viewing geometry of the tail has improved it has grown longer, and during my recent observations it has appeared close to 10 arcminutes long.

LEFT: An image I took of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS on May 6, 2024 via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. RIGHT: A sketch I made of the visual appearance of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS through my 41-cm reflector on the evening of June 2, 2024.

LEFT: An image I took of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS on May 6, 2024 via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. RIGHT: A sketch I made of the visual appearance of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS through my 41-cm reflector on the evening of June 2, 2024.

What the current lack of brightening portends for Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is difficult to predict at this time. For the time being, at least, I remain cautiously optimistic of the bright future display that I (and others) have been hoping for, as it continues to appear healthy, and any talk of a "fizzle" would strike me as being premature. However, if, after another one to two months, there has been no further brightening (and especially if there has been a distinct fading), then I would likely begin to have serious reservations as to whether that potential bright display will really happen. The fact that the dust tail is so well-developed this far in advance of perihelion continues to remain a good sign since, as I indicated above, that suggests the possibility that there could be some significant brightness enhancement due to forward scattering of sunlight. As is true for just about any comet that enters the inner solar system, we will just have to wait and see what happens.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 June 3.16 UT, m1 = 10.2, 0.9' coma, DC = 6-7, 9' tail in p.a. 105 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (August 15, 2024): I was able to follow Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS until early July before it sank too low in my southwestern sky to observe any further. It was still near 10th magnitude when I last saw it, continuing the stagnation in brightness that it had exhibited during the preceding three months -- which could perhaps be an ominous sign for the potential bright display we had been hoping for later this year. However, the comet remained accessible from the southern hemisphere for another month, and according to observers there it finally began brightening again, and was between magnitudes 8 1/2 and 9 when it sank into their evening twilight during early August.

The comet's behavior during the past several months has fueled a lot of speculation as to what kind of show will greet us in October. There is perhaps some evidence that it might be on the verge of disintegrating, and that we'll see little, if anything, come October, but there is also evidence that the opposite may occur. According to the observers in the southern hemisphere, as well as the images many of them have obtained, the comet remained healthy in its overall appearance as it began disappearing into twilight, and in fact was also beginning to exhibit a distinct ion tail in addition to the prominent dust tail that it has been exhibiting for the past few months.

Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is now inaccessible even from the southern hemisphere, and will be in conjunction with the sun (11 degrees south of it) at the beginning of September. As I mentioned above, it makes a brief appearance low in our morning sky during the latter part of that month, and what we see then -- provided we see anything at all -- should, hopefully, give us a pretty good idea of what kind of show, if any, we'll see the following month. For now, we wait . . .

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 July 7.15 UT, m1 = 10.1, 1.3' coma, DC = 5, 13' tail in p.a. 105 (41 cm reflector, 41x)

UPDATE (October 15, 2024): Any speculation that Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS might disintegrate en route towards or during its perihelion passage has now been dramatically shown to be incorrect. During the past few days it has become a truly spectacular object, a borderline "Great Comet," and at this time I personally rank it as being the 5th-best comet I have ever observed.

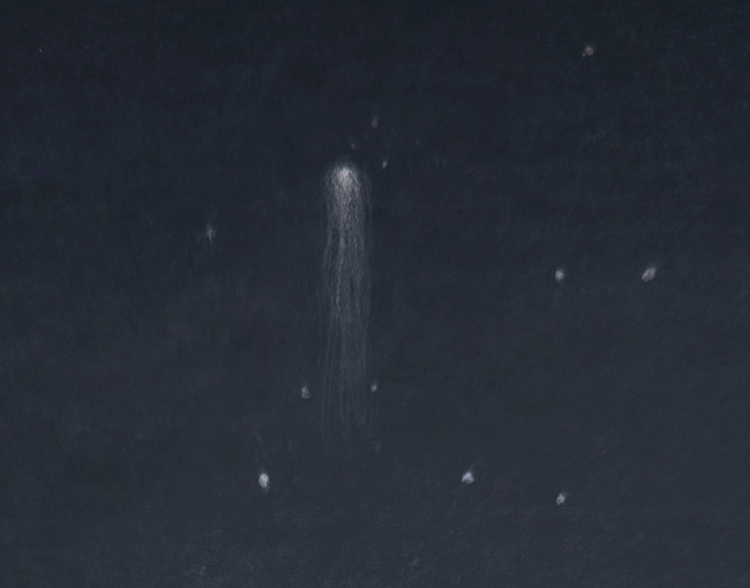

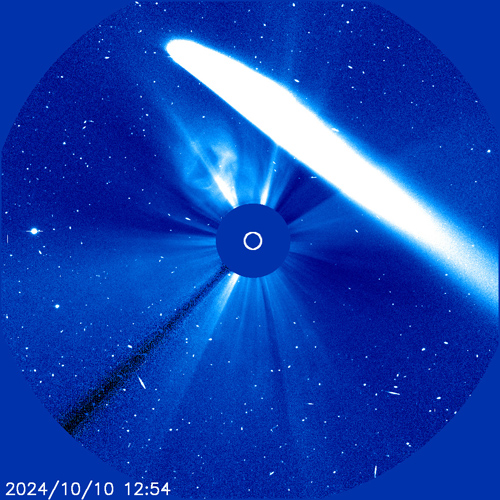

Because of some personal issues that I may discuss in a future tally entry, I ended up missing the comet's entire appearance in the morning sky in late September. According to the images I've seen and reports I've read -- primarily from observers in the southern hemisphere, where it was better placed for observation -- it was a bright and easily observable object despite its low elongation, and by the time it disappeared back into the dawn sky around the beginning of October it had reached 1st or 2nd magnitude and was exhibiting a bright dust tail up to 20 degrees long or longer. A few days later it put on a spectaular show as it crossed the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO, with a bright tail that lingered for several days after the coma had exited the field.

The stage was now set for the comet's long-awaited evening sky appearance. I first saw it on the evening of October 12, when despite its being at an elongation of only 17 degrees I could see it with my naked eye without much difficulty, with a tail approximately two degrees long in 10x50 binoculars (and which possibly would have appeared even longer except there was a cloud in the vicinity). On the following night I could easily detect a naked-eye tail at least 10 degrees long, and on the subsequent night -- the 14th -- the naked-eye tail was at least 18 degrees long. (It's worth noting that these observations took place with a bright moon in the evening sky, and also -- due to the aformentioned personal issues -- I am presently forced to observe from a location which has non-trivial, although not overwhelming, light pollution.) In part due to a lack of suitable reference objects, the comet's brightness has been somewhat difficult to measure, but an educated "guesstimate" places it around 1st magnitude, possibly with a little bit of fading by the most recent night.

LEFT: Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS in the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO on October 10, 2024. Courtesy NASA/ESA. RIGHT: A photo I took of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS on the evening of October 13, 2024. A faint "anti-tail" can be seen extending in the direction opposite of the main tail.

LEFT: Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS in the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO on October 10, 2024. Courtesy NASA/ESA. RIGHT: A photo I took of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS on the evening of October 13, 2024. A faint "anti-tail" can be seen extending in the direction opposite of the main tail.

Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS is continuing to climb higher each evening, plus we are continuing to get a more and more broadside view of the dust tail, so the apparent length of that tail should keep increasing for at least a little while. The comet itself will likely fade as it recedes from the sun and Earth, but even so, we may get our best views in about a week once the moon clears from the evening sky and the tail may be near its maximum apparent length. Afterwards it should remain a fairly easily detectable object through the end of the year, as described above.

The personal issues I mentioned earlier will almost certainly have some effect on how I am able to follow Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS from here on out, and on whatever additional comets I might be able to observe. I am cautiously optimistic that I will be able to keep my observational activity at some level for at least the very near-term future, but as I mentioned at the beginning of this entry as well as numerous places elsewhere in these pages I've pretty much had plans to "retire" at the end of this year, and the personal issues have placed a fairly emphatic stamp on those plans. I'm very glad that Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS came through and provided such a dramatic and spectacular show during these final weeks and months as I likely begin to wrap things up.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 October 15.07 UT, m1 = 1.6:, tail 18 degrees long in p.a. 100 (naked eye)

750. COMET ATLAS C/2022 E2 Perihelion: 2024 September 14.13, q = 3.666 AU

The new year of 2024 has now arrived. As I have indicated in numerous previous entries, for some time I have looked towards 2024 as being my final year of sustained active visual observational astronomy, with a likely "retirement" from such activities at the end of the year. Now that 2024 is finally here, I am not at all clear in my mind as to what will happen once the year ends, although I am leaning towards fulfilling that "retirement," at least, in general terms. However, as I have also indicated in several previous entries, I suspect I will retain the caveat of "coming out of retirement" on brief occasions if something bright or interesting comes along and for notable events, but this would likely be on just an intermittent basis. I will know a lot more, I would think, as to how I will proceed in 12 months' time when the appointed time arrives.

And . . . the first comet I added to my tally in what will likely be my last year of sustained visual comet observing marks a significant milestone: my 750th comet, three-fourths of the way to 1000. It has taken me 54 years to reach this almost unbelievable number . . . As I mentioned a few entries back I have recently passed a couple of other significant milestones within the fairly recent past, with this one still remaining, and now I have achieved it. Especially in light of my likely "retirement" at the end of this year, there are no other significant milestones that I have any realistic expectations of achieving, and of course I have no expectations of ever reaching 1000. (For what it's worth, since I achieved comet no. 500 twelve years ago, that would suggest that, if I were to continue observing at the pace I have been at since then, I might reach comet no. 1000 sometime around the year 2036 -- during which I would pass the age of 78 -- but of course I just don't see that happening.)

My "milestone" comet is a dim and distant (albeit intrinsically bright) long-period object discovered as long ago as March 7, 2022 -- my 64th birthday -- by the ATLAS program's telescope located in Chile, with pre-discovery images taken by that same telescope twelve days earlier being identified shortly thereafter. (It is not one of the "Dependable Dozen" -- of which there are still three left to go -- but it is one of the "maybe" comets I alluded to in that discussion.) At the time if its discovery Comet ATLAS was located at a heliocentric distance of 8.30 AU and was a little over 2 1/2 years away from perihelion passage, and was located in southern skies at a declination of -32 degrees. Incidentally, Comet ATLAS is the fourth comet on my lifetime tally that was discovered on my birthday: two of these are very early objects, Comet Toba 1971a (no. 6) being discovered on my 13th birthday, in 1971, and the naked-eye Comet Kohoutek 1973f (no. 10) being discovered on my 15th birthday, in 1973. More recently, on its 2016 return Comet 53P/Van Biesbroeck (no. 598) was recovered on my 56th birthday, in 2014.

Comet ATLAS is traveling in a moderately-inclined retrograde orbit (inclination 137 degrees). It was near opposition around the time it was discovered, with a brightness between 18th and 19th magnitude, and was followed for the next few months before disappearing into evening twilight en route to conjunction with the sun in late August. It was picked up again during the latter months of 2022 and followed quite extensively as it went through opposition in February 2023; according to various reports I've seen it was around 15th to 16th magnitude throughout much of that time. After another conjunction with the sun in August the comet started being picked up in the morning sky during October, and I obtained my first set of images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network at the end of that month, with its appearing near 15th magnitude. More recent images I've seen, including additional LCO images I obtained in mid-December and in early January 2024, have shown that it has brightened since then and is also exhibiting a distinct tail, and when I made my first visual attempt, late in the evening of January 10, I clearly detected it as a small and relatively condensed object slightly brighter than 14th magnitude, that exhibited distinct motion during the half-hour that I followed it.

Comet ATLAS is currently located in southern Cancer 1 1/2 degrees west-northwest of the star Omicron Cancri (and approximately five degrees southeast of the Praesepe star cluster M44), and is traveling towards the west-northwest at just under half a degree per day; it passes two degrees southwest of M44 on January 24 and then goes through opposition two days later, when its elongation will be almost exactly 180 degrees. It crosses into Gemini in mid-February, goes through its stationary point in early May, and passes just over 15 arcminutes northwest of the star Theta Geminorum on May 22 before disappearing into evening twilight within the next couple of weeks. After conjunction with the sun (15 degrees north of it) in early July the comet begins emerging into the morning sky during the latter part of August, at which time it will be located in far northeastern Auriga and traveling slowly northeastward. After passing through its stationary point in mid-September -- just after perihelion passage -- it begins traveling more rapidly northwestward through Lynx and then Camelopardalis, entering northern circumpolar skies in late October and passing through opposition in early December, at which time it will be at its farthest north point (declination +68.5 degrees) and its closest to Earth (2.99 AU). The comet subsequently starts traveling towards the southwest, passing directly across the nearby galaxy IC 342 (three arcminutes south of the galaxy's center) on December 11 and crossing into Cassiopeia a week later and then into Andromeda shortly after mid-February 2025. Afterwards it starts entering evening twilight en route to its next conjunction with the sun (38 degrees north of it) in mid-April.

Since Comet ATLAS is so distant I don't expect it to become bright, and in all honesty I will probably be observing it only infrequently. It may brighten by a few tenths of a magnitude by the time I lose it in twilight about four months from now, and it may be around 13th magnitude when near opposition late this year, but while I may observe it on an occasional basis during that time frame I suspect most of my attention will be devoted to the preceding comet. There is a theoretical possibility that Comet ATLAS might still be bright enough for visual observations when it becomes accessible in the morning sky after mid-2025 en route to its next opposition in September, but by then the time will have come for me to leave those efforts to other observers.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 January 11.23 UT, m1 = 13.7, 0.4' coma, DC = 6-7 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

UPDATE (September 5, 2024): Following its conjunction with the sun a couple of months ago, Comet ATLAS began emerging into the morning sky during August, and I had hoped to try for it visually shortly before mid-month, however -- due in no small part to the location of trees in that direction from my main observing site -- it was still too low for me to make a serious attempt. After waiting through the subsequent full moon I was finally able to make such an attempt this morning, and despite the fact I had to play "dodge-the-clouds" and had clear skies in that direction for only a few minutes, I successfully viewed the comet as a small, moderately condensed object slightly fainter than 13th magnitude.

Comet ATLAS is now just a little over a week away from perihelion passage. The viewing circumstances over the next few months are described above, and it may be about a half-magnitude or so brighter than its present brightness around the time it is at opposition. I will probably observe it on an occasional basis through about the end of this year.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 September 5.45 UT, m1 = 13.4, 0.4' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

<-- Previous

Next -->

BACK to Comet Resource Center