TALLY ENTRIES 751-760

I commented in the previous entry that this new year of 2024 will quite likely be my final year of sustained visual comet observing. It is thus only fitting that it should be a busy year for comets, and indeed there are several bright and/or interesting ones that I have expectations of observing, some of which I have already picked up and others which are still on the way in. In keeping with that expectation, by the middle of January I had already added two new comets to my lifetime tally.

My second tally entry of 2024 -- the tenth comet of the "Dependable Dozen" -- is a long-period object discovered by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii back on September 24, 2021, when it was located at a heliocentric distance of 8.92 AU and almost 2 1/2 years away from perihelion passage. Despite its distance it was nevertheless bright enough (around 19th magnitude) that I was able to obtain a couple of images of it a few days later (when it was still listed on the Minor Planet Center's Possible Comet Confirmation Page) via the Las Cumbres Observatory network, and the astrometric measurements from these are included on the comet's discovery announcement. This is, incidentally, the 30th Pan-STARRS-discovered comet that I have observed visually, of 303 Pan-STARRS-named comets at this writing, i.e., almost exactly 10%; since I have seen one of these on two different returns the name "PANSTARRS" now appears on my tally 31 times, in second place behind LINEAR (with 75 appearances).

Comet PANSTARRS is traveling in a somewhat steeply-inclined direct, or prograde, orbit (inclination 59 degrees). It has brightened steadily ever since its discovery, and was most recently at opposition in December 2022; various reports and images then and throughout the first few months of 2023 indicated a total brightness close to 15th magnitude and the presence of a distinct tail. After conjunction with the sun (45 degrees south of it) in July 2023 it began a slow emergence into the southern hemisphere's morning sky, although the elongation remained quite small for some time and the reports and images I have seen remained relatively scarce, with the images I did see showing the tail as becoming more and more prominent. The first visual observations from southern hemisphere observers, around early December, indicated a total brightness near 11th magnitude. I was finally able to obtain some LCO images of the comet in late December, which were consistent with this reported brightness and which showed the tail as being over 15 arcminutes long. I've had to wait a while longer to make my first visual attempt, but when I was able to do so on the morning of January 14, despite its being at an altitude of only 12 degrees (due to its declination of -34 degrees) I could easily detect it near magnitude 10 1/2, and even despite less-than-ideal sky conditions I could detect the initial few arcminutes of the tail.

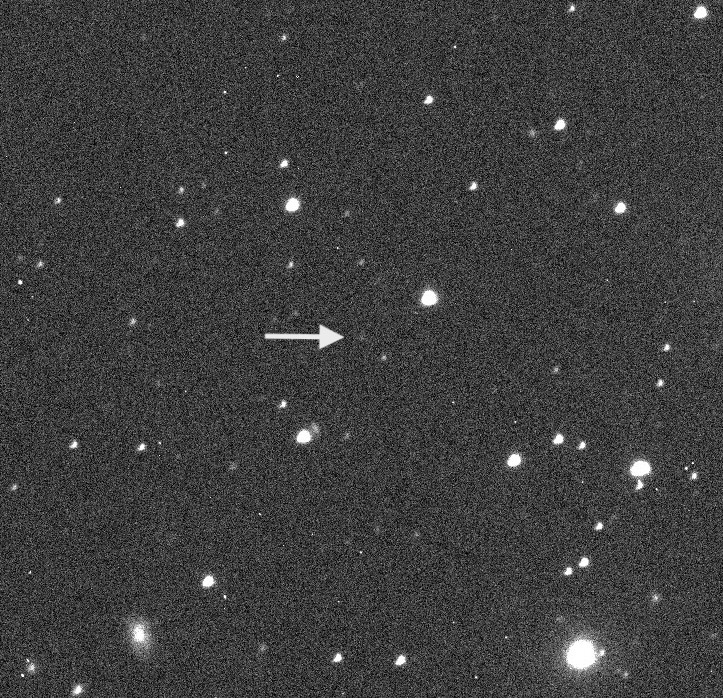

Images of Comet PANSTARRS C/2021 S3 I've obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: October 2, 2021 (eight days after the comet's discovery), from the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The astrometric measurements from this image were included on the comet's discovery announcement. RIGHT: December 26, 2023, from the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. This is the full 30x30 arcminute image; when examined under enhanced contrast the tail extends almost all the way to the edge.

Images of Comet PANSTARRS C/2021 S3 I've obtained via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: October 2, 2021 (eight days after the comet's discovery), from the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The astrometric measurements from this image were included on the comet's discovery announcement. RIGHT: December 26, 2023, from the LCO facility at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. This is the full 30x30 arcminute image; when examined under enhanced contrast the tail extends almost all the way to the edge.

Initial projections suggested that Comet PANSTARRS might become as bright as 7th magnitude and perhaps even flirt with naked-eye visibility, however it is presently running about two magnitudes fainter than those early projections; since it may be a first-time visitor from the Oort Cloud this is perhaps not especially surprising. It remains a morning-sky object for the next few months, being currently located in northeastern Lupus about one degree northwest of the star Chi Lupi and traveling towards the northeast at slightly under one degree per day; over the next few weeks it crosses through Scorpius (passing 1 1/2 degrees southeast of the bright star Antares on January 30), Ophiuchus (passing 20 arcminutes southeast of the globular star cluster M9 on February 13 and 10 arcminutes southeast of the globular star cluster NGC 6356 a day later), Serpens Cauda, Aquila, Sagitta, and Vulpecula (crossing the western regions of the "Coathanger Cluster" Collinder 399 on March 30), before entering Cygnus during the second week of April. The comet is closest to Earth (1.29 AU) on March 15 and may be near its brightest -- perhaps a magnitude or so brighter than it is now -- around that time.

Comet PANSTARRS curves gradually more and more directly northward as it crosses the dense star fields of the Cygnus Milky Way during late April, and passes through its stationary point at the end of May. Shortly thereafter it enters northern circumpolar skies, passing just over half a degree west of the nearby spiral galaxy NGC 6946 on June 14 and subsequently traveling essentially westward through southwestern Cepheus and then Draco as it reaches its peak northerly declination (+62.8 degrees) on July 10 and goes through opposition a week later. The comet goes through its other stationary point just before the end of August and after that travels towards the southeast (gradually curving more directly eastward) as it starts to disappear into evening twilight around February 2025. It will almost certainly have faded below the limit of visual detectability well before then, probably around the July/August timeframe.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 January 14.51 UT, m1 = 10.4, 1.5' coma, DC = 3-4, 3.5' tail in p.a. 255 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

752. COMET 13P/OLBERS Perihelion: 2024 June 30.05, q = 1.175 AU

This is a comet that I have been diligently awaiting for quite some time. Among other things, it is the 11th comet of the "Dependable Dozen" to show up on my tally; only one more of that particular group remains to be added, and that is still several months away. This is one of the "classical" Halley-type comets, and about a quarter-century ago I learned that it, along with another such comet, 12P/Pons-Brooks, would be returning in 2024 -- which was quite a ways in the future at that time but which the wheel of time has now brought to the present. I picked up Comet Pons-Brooks a little over six months ago (no. 740), and it has undergone several outbursts since then and is presently visible in binoculars near 8th magnitude, low in the northwestern sky after dusk. And now, I have picked up this one as well . . .

The comet was originally discovered on March 6, 1815 by the German astronomer Heinrich Olbers, who is perhaps best known as being a member of the "Celestial Police" that formed in 1800 to search for a presumed planet between Mars and Jupiter. Although the "Police" were beaten at this task by the Sicilian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi, who discovered what is now known as the asteroid (1) Ceres at the beginning of 1801, Olbers nevertheless went on to discover two of the next three known asteroids, (2) Pallas in March 1802 and (4) Vesta in March 1807. (Vesta was the first destination for NASA's Dawn spacecraft, which orbited it from mid-2011 to mid-2012.) Olbers also discovered two long-period comets, in 1780 and 1796, and is also known for articulating what is now known as "Olbers' Paradox" (concerning the darkness of the nighttime sky) in 1823.

Olbers' comet reached a peak brightness between 5th and 6th magnitude around the time of its perihelion passage in late April 1815. The observations during that return were sufficient to show that the comet had an orbital period of slightly over 70 years, with a perihelion passage expected in the mid- to late 1880s. It was "discovered" (as an apparently unknown comet) by the champion American comet discoverer William R. Brooks on August 25, 1887, with subsequent calculations soon showing its identity with Olbers' comet and a perihelion passage in early October. A somewhat distant approach to Jupiter (1.52 AU) in early 1889 shortened the orbital period slightly, to just under 70 years, and the comet was next recovered by then-Czechoslovakian astronomer Antonin Mrkos -- discoverer of several comets in the mid-20th Century, including the bright naked-eye Comet Mrkos 1957d -- in January 1956. Comet Olbers passed through perihelion in mid-June and reached a peak brightness near 7th magnitude, and was followed until late September.

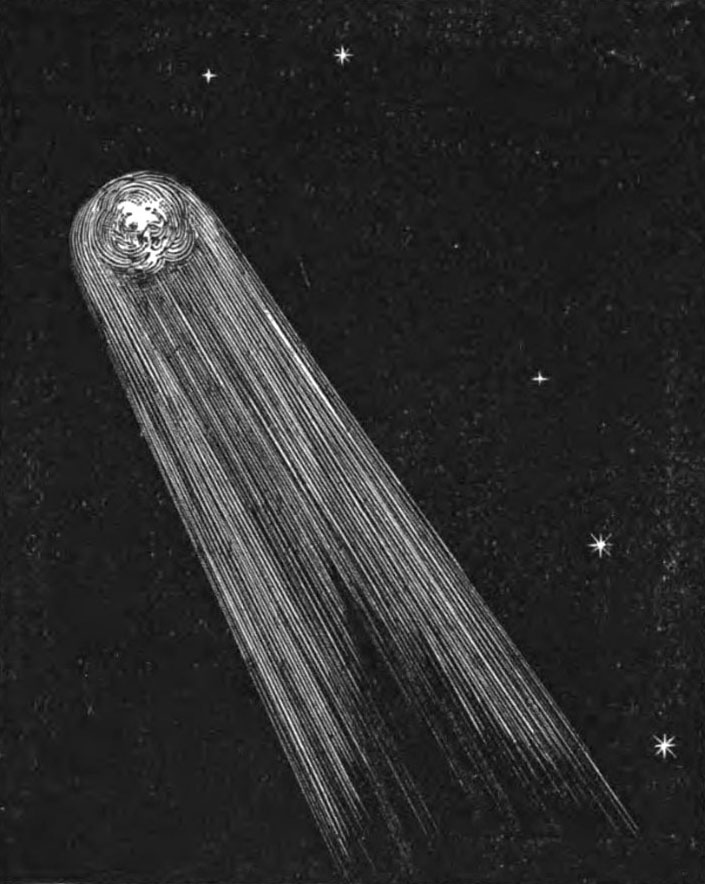

LEFT: Comet P/Olbers as sketched by William R. Brooks on October 14, 1887. RIGHT: Photograph of Comet P/Olbers taken by George Van Biesbroeck from Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin on June 30, 1956.

LEFT: Comet P/Olbers as sketched by William R. Brooks on October 14, 1887. RIGHT: Photograph of Comet P/Olbers taken by George Van Biesbroeck from Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin on June 30, 1956.

As Comet Olbers was approaching its 2024 perihelion it occurred to me that I might be able to make the recovery. I began making attempts with the telescopes of the Las Cumbres Observatory network in early October 2022, and after an initial false alarm I continued to make unsuccessful semi-regular attempts up through mid-January 2023, after which the comet began disappearing into twilight. It was in conjunction with the sun in early May, and after it began emerging into the morning sky I made my next attempt in mid-June, and thereafter continued making attempts on a roughly semi-monthly basis. As before, these various attempts were all unsuccessful.

On August 24, 2023 I took two 10-minute exposures with one of the 1.0-meter LCO telescopes based at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. When I examined these images I spotted a very faint (22nd magnitude) moving starlike object near the expected line of variation at a perihelion difference of -0.73 days (approximately 17.5 hours) compared to the Minor Planet Center's prediction. I immediately ordered up a new set of images to try to confirm this, but in the meantime, armed with the knowledge of exactly where to look, I was able to spot extremely faint images on a pair of exposures I took with one of the 1.0-meter LCO telescopes at the South African Astronomical Observatory on August 13, that were consistent with my August 24 suspect. (These images were very weak, and I am not surprised that I failed to notice them at the time.) Meanwhile, two different pairs of images I obtained via the LCO telescopes at SAAO on the 25th showed the same moving object in a location that was consistent with my suspect, as did images I obtained over the next couple of nights with LCO telescopes at both locations based upon a preliminary orbital calculation by Syuichi Nakano that utilized my astrometric measurements as well as a linkage with measurements made in 1887 and 1956. I received notification from the Minor Planet Center that my recovery looked good, and in addition to acknowledgement on the next Minor Planet Electronic Circular of comet positions and orbits, I was officially credited with the recovery by the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams and by a press release issued by LCO. Needless to say, I have found this all quite gratifying, and I glad that all the effort I put into these recovery attempts paid off.

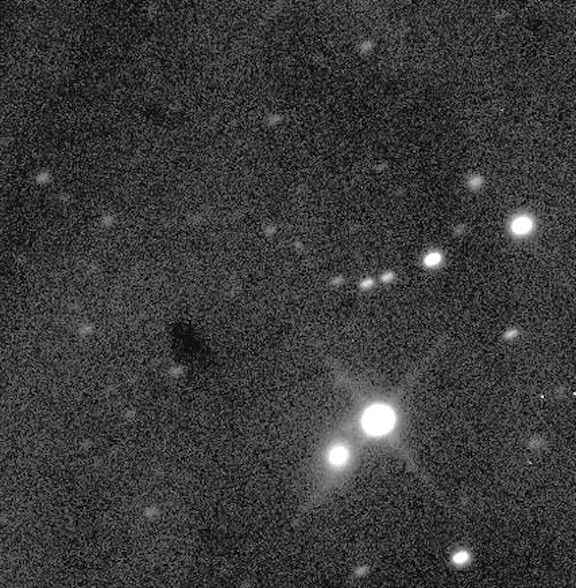

The recovery images of Comet 13P/Olbers, taken on August 24, 2023 with a 1.0-meter LCO telescope based at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. These are consecutive 10-minute exposures.

The recovery images of Comet 13P/Olbers, taken on August 24, 2023 with a 1.0-meter LCO telescope based at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. These are consecutive 10-minute exposures.

Ever since my recovery I have continued to image Comet Olbers on a roughly bi-weekly basis, and of course other observers have imaged it as well. It brightened steadily during the intervening weeks, as well as developing a distinct coma and the apparent beginnings of a short tail in the process. LCO images I took during January 2024, including a set I obtained on January 29, revealed its continued brightening, and suggested that the comet might now be bright enough to be worth attempting visually. On my first attempt, on the evening of February 1, I successfully detected it as a faint, somewhat condensed object of magnitude 13 1/2. (I had hoped to be the first observer to pick it up visually, but it appears I was beaten to the punch by my colleague Chris Wyatt in New South Wales, who picked it up a little over 15 hours before I did.) The overall brightness and appearance were similar when I observed the comet again three nights later.

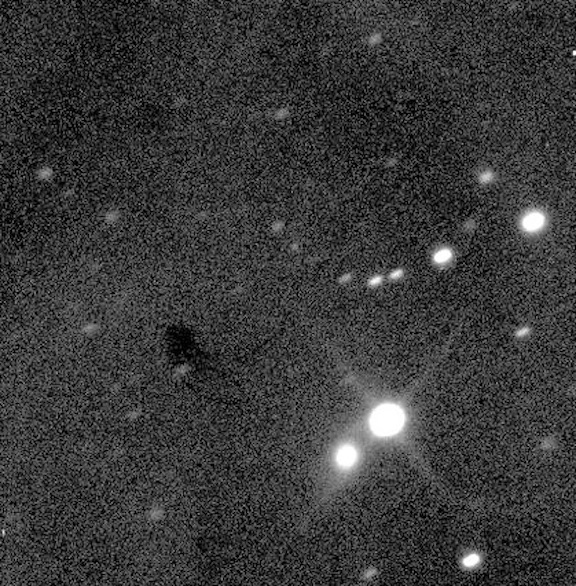

Images of Comet 13P/Olbers I obtained via the 0.35-m LCO telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory. Both images are 3-minute exposures. LEFT: January 3, 2024. RIGHT: January 29, 2024.

Images of Comet 13P/Olbers I obtained via the 0.35-m LCO telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory. Both images are 3-minute exposures. LEFT: January 3, 2024. RIGHT: January 29, 2024.

Comet Olbers is traveling in a moderately-inclined direct (or prograde) orbit (inclination 44.5 degrees). As is also the case with Comet Pons-Brooks, the viewing geometry during this return is rather mediocre, with the comet's being on the far side of the sun from Earth when at perihelion; for what it's worth, those of us in the northern hemisphere will certainly have the better view. The return is fairly similar to that of 1956, with the date of this year's perihelion being just two weeks later than the corresponding date from that year.

The comet was at opposition just after mid-November 2023 and is presently in the evening sky, being currently located in far northwestern Eridanus 2 1/2 degrees southwest of the star 5 Eridani and traveling almost due northward at 20 arcminutes per day. Over the coming weeks it curves toward the northeast and accelerates, crossing into Cetus in mid-February (and passing half a degree east of the star Alpha Ceti on February 29), into Taurus during the latter part of March (and passing between the Pleiades and Hyades star clusters during mid-April), and then into Auriga during the second week of May, where it passes 10 arcminutes southeast of the open star cluster M36 on May 21. In early May the elongation drops below 30 degrees, by which time the comet is traveling towards the east-northeast at 40 arcminutes per day, and the elongation reaches a minimum of 26 degrees at the end of the month. Shortly after mid-June the comet crosses into Lynx, and it reaches a maximum northerly declination (+42.4 degrees) on June 30 (the date of perihelion passage), at which time the elongation goes back over 30 degrees.

Now traveling towards the east-southeast, Comet Olbers crosses northeastern Leo Minor during the second half of July, being nearest to Earth (1.89 AU) on July 20, when its elongation is 35 degrees and it will be traveling at its maximum rate of slightly over 1 degree per day. Shortly before the end of July the comet crosses into southwestern Ursa Major and then into Coma Berenices two weeks later; during the middle days of August it passes directly across the Coma Berenices Star Cluster (Melotte 111). The elongation reaches a maximum of 40 degrees around August 23, and the comet crosses into Bootes in early September and then into Virgo during the last week of that month.The elongation again drops below 30 degrees during the second week of October, and within another couple of weeks the comet disappears into evening twilight.

The historical data seems to suggest that Comet Olbers brightens fairly rapidly as it approaches perihelion, and indeed its recent behavior supports this. It may be between 10th and 11th magnitude during March, between 9th and 10th magnitude during April, and perhaps 8th magnitude during May. (Curiously, during mid-April Comets Pons-Brooks and Olbers -- traveling in opposite directions -- will pass some 17 degrees from each other, with Pons-Brooks being a few magnitudes brighter but quite a bit lower in the sky.) Comet Olbers should reach a peak brightness between 6th and 7th magnitude during June and July and should then fade afterwards, but may still be around 10th of 11th magnitude when it disappears into the dusk during October. For what it's worth, I have read one report from 1956 that suggests that, about six weeks after perihelion passage, the comet might have undergone an outburst to about 6th magnitude; perhaps we might see something like that this time around.

Comet Olbers has a rather deep personal significance to me, which is perhaps a good part of the reason why I invested so much effort into my attempts to recover it. Its previous return in 1956 came less than two years before I was born, and, indeed, my parter Vickie's parents were married in September 1956, just before the final observations of that return were made. And, it is bringing more significant events to my personal life: on the day before I picked it up Vickie and I, who began dating seven years ago and after five years of living together as a "domestic partnership," agreed to get married later this year (date undetermined at this writing, but probably sometime during the summer). And then, on February 4, my older son Zachary and his partner Karina welcomed into the world their first (and what may very well be their only) child, my newest grandson Santiago Ezekiel. This is my second biological grandchild, and my third grandchild overall.

With regard to the "retirement" from visual observational activities that I have often discussed in these pages, my original thought had been to do so once I was finished with Comet Olbers, however the discovery last year of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS C/2023 A3 (no. 749) and its potential bright display later this year has caused me to delay that event until around the year of this year. As for Comet Olbers, it should still be followed with larger telescopes for some time, and I may even try to image it myself from time to time with the LCO telescopes; around the time of its opposition in June 2025 it will be traversing the very rich star fields of the Sagittarius Milky Way. It so happens that the next return, in 2094 (perihelion late March) will be the most favorable one since its original discovery, with its passing 0.76 AU from Earth and probably reaching a peak brightness of at least 5th magnitude. I will be long gone well before then, of course, but perhaps one or more of my grandchildren -- all three of whom will be a bit older then than I am now -- will be able to see it, or -- perhaps even more likely -- one or more of their children may see it and, in a sense, carry on my personal story with this most memorable comet.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 February 2.09 UT, m1 = 13.6, 0.7' coma, DC = 3-4 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (May 4, 2024): Comet Olbers has brightened rather steadily more-or-less in line with the above predicted scenario, and at this writing it has reached 9th magnitude and is marginally detectable with 10x50 binoculars. Its low placement above the horizon, however, makes it a bit more challenging to see than that brightness might suggest, and as mentioned above the elongation will remain 30 degrees or less for the next two months. (Furthermore, it is not in a very good direction from my main observing site, although I can relieve this situation somewhat by motoring to a nearby site.) As it (presumably) continues to brighten during these next two months I am cautiously optimistic of being able to maintain a semi-regular watch on it.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 May 4.13 UT, m1 = 8.7, 4.5' coma, DC = 4-5 (10 cm SCT, 40x)

UPDATE (June 30, 2024): Slightly over ten months after I recovered Comet Olbers last August, it has now arrived at perihelion. As I mentioned in the previous update, it has remained quite low in the northwestern sky for the past couple of months, although, as hoped, I was pretty much able to keep it under observation throughout that time. The elongation has now gone back over 30 degrees, however following the late June full moon my location here has been besieged by an almost continuous flurry of rain and cloudy days and nights -- apparently, an early onset of our annual summer monsoon -- and I was accordingly unable to obtain any observations. Finally, on the evening of June 29 -- which coincided with Comet Olbers' perihelion passage -- I had a clear night, and was easily able to see the comet in 10x50 binoculars near 6th magnitude with a faint, broad tail extending towards the northeast.

Photograph (15-second exposure) I took of Comet 13P/Olbers on the evening of June 29, 2024, just 2 1/2 hours after its perihelion passage. The comet, with a wisp of tail extending just rightward of straight up, is below top center. The bright star to the comet's lower right is 31 Lyncis.

Photograph (15-second exposure) I took of Comet 13P/Olbers on the evening of June 29, 2024, just 2 1/2 hours after its perihelion passage. The comet, with a wisp of tail extending just rightward of straight up, is below top center. The bright star to the comet's lower right is 31 Lyncis.

Comet Olbers will still be approaching Earth for the next three weeks, and I don't expect much change in brightness throughout that time, although as its elongation increases it should become easier to observe. Hopefully, the weather in these parts will allow me to do so.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 June 30.16 UT, m1 = 6.3, 7' coma, DC = 4, 20' tail in p.a. 050 (10x50 binoculars)

753. COMET 207P/NEAT Perihelion: 2024 January 31.81, q = 0.938 AU

In a tally entry that I wrote a little over seven months ago, at which time I was about ready to enter the "home stretch" towards comet no. 750, I introduced the "Dependable Dozen," i.e., twelve comets that I expected to observe, and add to my tally, before the end of 2024. Since I added my 750th comet earlier this year the entire rationale for the "Dependable Dozen" may perhaps be a bit moot now, although as I've continued to add those particular comets I have nevertheless made mention of it. As I mentioned in its entry, the preceding comet was the 11th comet of that group, but the final member is still a few months away. Meanwhile, in the original discussion I made mention of several "maybes," and some of the comets that I have added during the intervening months have been among this group. This particular comet is another one of those "maybes."

The comet was originally discovered in May 2001 during the course of the Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) program that was developed and supervised by planetary scientist Eleanor "Glo" Helin; the discovery telescope was based at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. Calculations soon showed that it was rather faint intrinsically, and was a short-period object with an approximate orbital period of 7.7 years that was already two months past perihelion when discovered. Japanese astronomer Syuichi Nakano pointed out that the comet's orbit bears a rough similarity to that of the famous disintegrated Comet 3D/Biela, although the resemblance is rather superficial and is almost certainly nothing more than coincidence.

Comet NEAT next returned in 2008 and was duly recovered and numbered. The viewing geometry was somewhat favorable, and the reported brightnesses were enough to convince me that visual attempts might be worthwhile, however I was unsuccessful in detecting it. At the next return, in 2016, the viewing geometry was very unfavorable and the comet was not recovered.

On its present return Comet NEAT was recovered by French astronomer Francois Kugel on August 14, 2023, at which time it was a very faint and starlike object of 21st or 22nd magnitude. For the next few months it remained faint and essentially starlike, and only within the fairly recent past has it begun to brighten and display typical cometary activity like a coma and a tail. I first began imaging it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network in early January 2024, and the most recent set of images I took, on February 3, together with a recent report of a successful visual observation, suggested that it was now worthwhile for me to attempt visually. On the evening of February 4 -- the same day that my newest grandson Santiago Ezekiel was born -- I was able to detect it as a very faint and small object of 14th magnitude, that exhibited distinct motion over an interval of 20 minutes.

LEFT: Comet 207P/NEAT on February 3, 2024, as imaged by the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas. RIGHT: My older son Zachary, his partner Karina, and my new grandson Santiago Ezekiel, born on February 4, 2024, the same day that I added Comet NEAT to my tally.

LEFT: Comet 207P/NEAT on February 3, 2024, as imaged by the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas. RIGHT: My older son Zachary, his partner Karina, and my new grandson Santiago Ezekiel, born on February 4, 2024, the same day that I added Comet NEAT to my tally.

Comet NEAT's current return is, by far, the most favorable one that it has had since its discovery. Although perihelion passage was a week ago it is still approaching Earth, and will pass a relatively close 0.220 AU from our planet on March 5. Presently it is located in southeastern Cetus a couple of degrees southwest of the star Sigma Ceti and is traveling almost due eastward at roughly 1 1/4 degrees per day; over the next few weeks it accelerates and gradually curves northward, crossing through Eridanus, Lepus, and then Monoceros. At the time of its closest approach to Earth it will be located about 2 1/2 degrees north of the star Theta Leporis and traveling at its maximum rate of slightly under three degrees per day. The comet may brighten to perhaps 13th magnitude by the time of its approach, but once it begins receding from Earth it will likely commence fading quite rapidly, and will probably drop below the limit of visual detectability by the latter part of March. At most, I will probably only be getting a handful of visual observations of it.

For what it's worth, three returns from now, in 2047, Comet NEAT will pass 0.16 AU from Earth -- about the closest possible approach in its current orbit -- in early February, and should reach a peak brightness near 12th magnitude. Even if I am still alive at the age of 88 I have no expectations of observing it then -- especially since it will be traveling through southern circumpolar skies throughout most of that time -- but hopefully the comet observers of that era will be able to follow it well.

With the addition of Comet 207P/NEAT to my tally I have now observed 152 numbered periodic comets (of 472 periodic comets that have been numbered as of this writing). One periodic comet that I observed on its discovery return -- Comet NEAT P/2001 Q6 (no. 296) -- has recently been recovered, and will automatically give me my 153rd numbered periodic comet when it receives a permanent number, which should be taking place within the relatively near future. (I have already imaged this comet via LCO, and it is conceivable that I might observe it visually around the time of its perihelion passage in late February, although the viewing geometry is only mediocre at best and the comet will likely remain too faint for visual detectability.) One other periodic comet that has recently been recovered (and that I have also imaged via LCO) and which should be numbered shortly may conceivably become bright enough for visual observations when it passes through perihelion a few months from now. There are a handful of other periodic comets that I observed on their respective discovery returns that may eventually be recovered and numbered at some point in the future, which accordingly would continue to give me additional numbered comets on my "observed" list from time to time. However, unless I continue observing at something other than a minimal level beyond my planned "retirement" at the end of this year, there are no additional already-numbered periodic comets that I have any reasonable expectations of adding to that list; 207P/NEAT was the last remaining member of that particular group of comets.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 February 5.10 UT, m1 = 13.9, 0.4' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

UPDATE (February 17, 2024): The newest batch of Minor Planet Circulars has assigned the designation 473P to Comet NEAT P/2001 Q6 which, as I noted above, gives me my 153rd numbered periodic comet as well as the highest-numbered periodic comet that I have observed (the overall highest-numbered comet now being 480P). The most recent images I have taken of Comet 473P/NEAT via the Las Cumbres Observatory network indicate that is continuing to brighten as it approaches perihelion, although whether or not it becomes bright enough to be detectable visually remains to be seen.

Meanwhile, Comet 207P/NEAT has, as expected, brightened somewhat, being near magnitude 13 1/2 when I last saw it a few nights ago. Moonlight is now precluding further observations for the time being, but hopefully once we are past full moon the comet will have brightened further as it nears its closest approach to Earth.

MOST RECENT OBSERVATION: 2024 February 14.09 UT, m1 = 13.6, 0.8' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 229x)

754. COMET 473P/NEAT P/2023 W1 Perihelion: 2024 February 26.24, q = 1.406 AU

It turns out that I was able to observe this comet after all. In my discussions of it in the previous entry, I expressed doubt that it would become bright enough to be visually detectable, but I was indeed able to do so. The comet may likely turn out to be a "one-time wonder," but at least I was able to see it, even if only briefly, this time around.

With a current orbital period of 22.5 years, Comet 473P/NEAT becomes the comet with the third-longest orbital period that I have seen on two returns, behind 38P/Stephan-Oterma and 27P/Crommelin. Meanwhile, it has the longest orbital period of any comet that I have seen on its discovery return and then a subsequent return, beating by one year the previous record-holder in that regard, Comet 161P/Hartley-IRAS, which I observed during its discovery return in 1984 (no. 63) and again in 2005 (no. 374). (Those returns, incidentally, came at significant times in my personal life: my initial observations of its discovery return coincided with my starting to work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, and my initial observation in 2005 came less than two weeks after my older son Zachary -- now a new Dad, as I discussed in the two previous entries -- graduated from High School. Depending upon what level of observational activity, if any, that I engage in after the end of this year, it is conceivable that I may see it on its next return, in late 2026, which is geometrically similar to its discovery return.)

Comet NEAT travels in a moderately steeply-inclined orbit with an inclination of 57 degrees. It was originally discovered in late August 2001 by the Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT) program, utilizing the 1.2-meter Oschin Schmidt Telescope at Palomar Observatory in California. I successfully imaged it on a couple of occasions during September with the CCD imaging system I had operational at the time, and on the second of those occasions it appeared bright enough to be worth attempting visually, and I successfully detected it (no. 296). I ended up following it visually for a little over 2 1/2 months, and it reached a peak brightness just brighter than magnitude 11 1/2. This was, incidentally, the first comet I added to my tally after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks here in the U.S., and the observational work I performed on this and other comets (including the obtaining and submitting of astrometric measurements) played a non-trivial role in settling and focusing my mind after that emotionally traumatic event.

As Comet NEAT approached its current perihelion passage I began making occasional recovery attempts with the Las Cumbres Observatory network in mid-September 2023, but all my attempts were unsuccessful. The comet was finally recovered on November 29 by Japanese amateur astronomer Hidetaka Sato, utilizing a remotely-controlled telescope in Chile. It turns out that the comet was located over a degree away from its predicted location (corresponding to a difference in perihelion time of over 2 1/2 days), and accordingly was outside of the range I was able to examine during my recovery attempts.

Once I learned of Hidetaka's recovery I successfully imaged the comet via LCO on December 3, and my astrometric measurements from these images as well as additional images I obtained on the 7th were included on the official recovery announcement. (Since the orbital solution there utilizes observations from both returns, my astrometric measurements from 2001 were also included within this solution.) I have continued to image the comet on a fairly consistent basis since then, and while it has brightened during the interim, as I pointed out in the previous entry the viewing geometry is relatively mediocre and I wasn't at all sure that it was becoming bright enough to be worth attempting visually. Nevertheless, on the evening of February 29 I did make an attempt, and -- through a wide gap between the trees to my west -- successfully detected it as a faint, diffuse, somewhat condensed object slightly brighter than 13th magnitude.

LEFT: CCD image I took of Comet 473P/NEAT on September 25, 2001, with the CCD imaging system I had operational at the time. This is a "stack" of four separate images, and accordingly there are four images of the background stars. I successfully obtained my first visual observation of the comet (no. 296) later that same night. RIGHT: The most recent Las Cumbres Observatory image I have taken of Comet 473P/NEAT, obtained February 8, 2024 via the LCO facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas

LEFT: CCD image I took of Comet 473P/NEAT on September 25, 2001, with the CCD imaging system I had operational at the time. This is a "stack" of four separate images, and accordingly there are four images of the background stars. I successfully obtained my first visual observation of the comet (no. 296) later that same night. RIGHT: The most recent Las Cumbres Observatory image I have taken of Comet 473P/NEAT, obtained February 8, 2024 via the LCO facility at McDonald Observatory in Texas

At the time of my visual observation Comet NEAT was located at an elongation of 45 degrees, in southern Andromeda four degrees northeast of the star Alpha Andromedae, and traveling towards the northeast at approximately 45 arcminutes per day. The elongation remains near 45 degrees for the next month before gradually increasing, but meanwhile due in part to the longer hours of daylight associated with spring it gets lower in the western sky after dusk, and for the next few months remains only slightly ahead of conjunction with the sun. On April 12 it passes about one degree southeast of the "Double Cluster" in Perseus, and by the end of that month enters northern circumpolar skies, reaching a peak northerly declination of +65.3 degrees in mid-May. Since it is now a few days past perihelion passage and is also receding from Earth I don't expect it to get any brighter, and indeed it will likely begin fading soon. Because of that, and because of its already low placement in the western sky, I really have no plans to look for it again.

As I mentioned in the preceding entry Comet 473P/NEAT is now the highest-numbered periodic comet I have observed, and moreover it also now has the distinction of being the highest-numbered periodic comet that I have observed on more than one return. The other recently-recovered comet I mentioned in the previous entry has also now been numbered, and if I am successful in observing it in about two months' time it will then become my highest-numbered observed periodic comet. As I also mentioned in that entry, that status may change if and when other periodic comets that I have seen on their respective discovery returns are recovered and numbered in the future, but we'll just have to see what that future holds as far as that is concerned.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 March 1.09 UT, m1 = 12.8, 1.0' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

755. COMET 479P/ELENIN P/2023 WM26 Perihelion: 2024 May 5.24, q = 1.244 UT

As I write these words, Vickie and I have recently returned from a road trip to Kerrville, Texas, where we had hoped to observe the total solar eclipse that took place on April 8. I had previously made arrangements with Schreiner University in Kerrville to utilize their 41-cm telescope to observe any comets that might be near the sun during totality: ideally, any SOHO Kreutz sungrazer that might be passing through perihelion shortly after that time, or, failing that, 12P/Pons-Brooks (no. 740), which was 25 degrees from the sun and close to 5th magnitude. As things turned out, a Kreutz sungrazer was in fact discovered in the C3 coronagraph about 10 hours before totality by Thai researcher Worachate Boonplod, however the images were weak and then contact with SOHO was temporarily dropped about 7 hours later, and with the lack of available data (and, at the time, some doubt as to whether or not this object even existed), I opted to devote my efforts to Pons-Brooks. (The comet did turn out to be real, and in fact showed up well in images taken by the C2 coronagraph after totality; meanwhile at least three ground-based observers managed to record it on wide-field images they obtained during totality.) However, most unfortunately I was completely clouded out; while I was able to obtain some momentary glimpses of the partial phases of the eclipse before and after totality during brief "thinnings" of the clouds, totality itself was a complete bust, and I never had any reasonable opportunity to even attempt any comet observations. This is the first time, after eight previous total solar eclipses I have observed, that I have been clouded out, and since it is distinctly unlikely I will travel to any such eclipses in the future -- with over 20 years elapsing before the next total eclipse crosses the U.S, at which time I would be (if still alive) in my mid-80s -- it appears I have to accept that I will never achieve my "bucket list" goal of observing a comet during a total solar eclipse. Such is the way life goes, sometimes . . .

Before we left for Kerrville I managed to add an additional comet to my tally, an object I have alluded to in a couple of previous entries. It was originally discovered on July 7, 2011 by Russian astronomer Leonid Elenin utilizing a remotely-controlled telescope of the International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) based in New Mexico. This was his second comet discovery, his first being C/2010 X1 (no. 487) which initially showed promise of becoming a bright object but which disintegrated as it approached perihelion (although a very faint remnant of its tail was observable for some time afterwards). Up through early 2017 he discovered three additional comets (for a total of five comets overall), all of these latter ones being rather faint objects having moderate to intermediate orbital periods.

At the time of Elenin's discovery the comet appeared as an almost starlike object of 19th or 20th magnitude, and in fact it was initially announced under an asteroidal designation, 2011 NO1. Calculations soon showed that it had passed through perihelion 5 1/2 months earlier, and was traveling in an elliptical cometary orbit with a period of slightly over 13 years; meanwhile, images taken by several observers showed that it was indeed a weakly active comet. On its subsequent return it was re-discovered by the Pan-STARRS survey in Hawaii on November 18, 2023, appearing as an asteroidal object which was found to be traveling in a cometary orbit, and it was later announced under the asteroidal designation 2023 WM26. This discovery announcement didn't come out until the latter part of December, and almost immediately German astronomer Maik Meyer reported its identity with Elenin's comet from 2011. Images soon began to show that it was definitely cometary.

The comet was a very faint object of 21st or 22nd magnitude at the time of its re-discovery by Pan-STARRS, but it has brightened quite rapidly since then. I began imaging it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network in mid-January 2024, and although it was quite faint on the initial LCO images I obtained, more recent sets of images showed it as brightening, and on a set I obtained in late March it appeared to be bright enough to be worth a visual attempt. On the evening of March 29 I suspected it as a diffuse object near 13th magnitude, however unfortunately it was located almost right next to a 10th-magnitude star that made this observation somewhat uncertain. After several nights of clouds and unsettled weather, including snowstorms on two consecutive days, I finally had decent conditions again on the evening of April 3 -- my last night in New Mexico before departing for Kerrville -- and was able to confirm my earlier suspect; the comet appeared diffuse and slightly condensed, just brighter than 13th magnitude.

At present Comet Elenin is located in southeastern Monoceros (in moderately rich Milky Way star fields) about four degrees southwest of the open star cluster M48, and is traveling towards the southeast at half a degree per day. In a few days it crosses into western Hydra, a constellation wherein it remains for the next 3 1/2 months, and meanwhile it gradually curves more and more directly eastward, reaching a maximum southerly declination of -29.3 degrees in early July. The comet is nearest Earth (0.62 AU) less than half a day before its passage through perihelion. There is very little information to go on regarding any expectations for its brightness, but based upon its recent behavior I suspect it might brighten an additional magnitude or so by the time it is nearest the sun and Earth and then begin fading afterwards, remaining visually detectable until perhaps sometime in June.

Comet 479P/Elenin becomes the 154th (and highest) numbered periodic comet that I have visually observed (of 483 periodic comets that have been numbered as of this writing). There are no more currently numbered periodic comets that I have any expectation of observing, although as I have mentioned in previous entries there are a handful of comets that I have observed on their discovery returns that would receive numbers if and when they are recovered, and thus my total would increase retroactively. It is always possible, of course, that there could be some surprise discoveries in the future that might further increase that total, but we'll just have to see what that future might hold.

CONFIRMING OBSERVATION: 2024 April 4.12 UT, m1 = 12.8, 1.0' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

756. COMET ATLAS C/2021 G2 Perihelion: 2024 September 9.21, q = 4.982 AU

One of the primary reasons why I have been able to amass so many comets in my lifetime tally is that, throughout most of the years that I have been engaged in this effort, I made attempts for just about any comet that I had reason to suspect might even possibly be bright enough for visual observations. Many of my attempts were unsuccessful, in fact, as of this writing I count 281 comets that I attempted but never succeeded in observing. At the same time, many of the ones I did succeed in observing were faint, distant, nondescript objects, and for example throughout "Countdown" I applied this description to quite a few of the comets I observed during that effort. Once I began the slowdown in visual observational activities a few years ago in preparation for what I envision will be my planned "retirement" at the end of this year -- now just eight months away -- I more or less gave up the practice of attempting any and all comets that might potentially be visible, and have concentrated my efforts on those that I was quite certain I would be able to see and on those that were bright and/or interesting in some way. Only a tiny handful of those 281 "non-successes" have come during this time.

Ordinarily, this particular comet is one that I would nowadays probably pass on, however its rather large perihelion distance somewhat intrigued me. It has the 16th largest perihelion distance of all the comets on my tally, and the 9th largest perihelion distance among all the long-period comets. Indeed, it has the largest perihelion distance of any comet that I have added to my tally in over eleven years.

The comet was discovered as long ago as April 11, 2021, by the ATLAS program based in Hawaii, at which time its heliocentric distance was 10.12 AU. Images at the time didn't show any convincing cometary activity, however, and its discovery was announced (over two months later) under the designation A/2021 G2. By the latter part of September 2021 images with large telescopes were beginning to show that it is definitely a comet, and subsequently it was re-designated as C/2021 G2. Since that time it has brightened steadily as it has approached closer to the sun, and various recent images I have seen, including a couple of recent sets I have taken with the Las Cumbres Observatory network, suggested it might be bright enough for visual observations, and when I made my first attempt, on the evening of April 28, 2024, I successfully detected it as a small and moderately condensed object of 13th magnitude -- actually a bit brighter than what I had expected.

Comet ATLAS was at opposition around the time of the March equinox and was closest to Earth (4.24 AU) around the middle of April. It is currently located at a declination of -31 degrees, in south-central Hydra a little over four degrees east-northeast of the star Xi Hydrae, and is traveling almost due northward at 10 arcminutes per day. It passes through its stationary point a week from now and afterwards begins curving slowly towards the northeast, crossing into Corvus in early June and eventually into Virgo in late August. The comet is probably as bright now as it is going to get and will probably begin fading -- albeit slowly -- fairly soon, and at most I will probably be getting only one or two additional observations of it. For what it's worth, after being in conjunction with the sun in mid-October it subsequently emerges into the morning sky and will be at opposition again in early May 2025, when it will be traversing northern Libra and perhaps will be only a few tenths of a magnitude fainter than it is now, however since that is after my planned "retirement" I doubt if I will be looking for it.

In one of my early "Countdown" entries I discussed how our knowledge of large-q comets has grown over the course of the past century, although it is somewhat curious that the overall distance records mentioned in that entry still stand, 17 years later. I also noted in that entry that my personal record for largest-q long-period comet was Comet Skiff C/1999 J2 (no. 277) at 7.110 AU, which I observed on a handful of occasions as an extremely faint, barely detectable object of 14th magnitude; that record also still stands. The largest perihelion distance of any comet on my tally is 8.454 AU, for the Centaur comet 95P/Chiron P/1977 UB (no. 196), which I followed for over three years around the time of its perihelion passage in 1996 but which visually never apppeared as anything other than a stellar 15th-magnitude object.

Any additional distant comets that I might observe from here on depend heavily upon what level of activity, if any, I might engage in once I "retire," however if I do decide to continue on at some reduced level there is at least one such comet that is already "on my radar screen," so to speak: this is the very distant, and intrinsically very bright, Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein C/2014 UN271, first noted on images taken in October 2014 during the course of the Dark Energy Survey at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, although these weren't noticed until quite some time later and the discovery wasn't announced until June 2021. This comet doesn't pass perihelion until January 2031, still at the enormous heliocentric distance of 10.950 AU, and since various recent images have suggested it may already be as bright as 16th or 17th magnitude it could conceivably be 14th magnitude or brighter -- and thus potentially detectable visually -- around the time of its perihelion passage (although since it will be fairly far south near a declination of -37 degrees when at opposition a couple of months later, I might have to wait another year, when it will be some 16 degrees farther north, for a realistic chance of seeing it). We'll see what things are like then . . .

And meanwhile, Comet 95P/Chiron went through aphelion in May 2021, and I successfully imaged it with the Las Cumbres Observatory network just a few days later; to my knowledge, these are the first observations of Chiron on its current "return." It passes perihelion again (at a heliocentric distance of 8.462 AU) in August 2046, and should once again reach about 15th magnitude. However, I would be 88 years old at the time, and over two decades beyond my "retirement," so even if I am still alive then I consider it very doubtful that I will be visually observing it.

Las Cumbres Observatory images I have taken of a pair of inbound distant comets. LEFT: The most recent image I have taken of Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein C/2014 UN271, on August 16, 2023 from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. I have slightly enhanced the contrast in order to bring out the faint coma. RIGHT: Image (from the LCO facility at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii) of the Centaur Comet 95P/Chiron on May 30, 2021, just three days after it had passed through aphelion. Several galaxies from the cluster Abell 76 are in the image; the brightest are IC 1568 (upper left), IC 1566 (above Chiron), and IC 1565 (lower right).

Las Cumbres Observatory images I have taken of a pair of inbound distant comets. LEFT: The most recent image I have taken of Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein C/2014 UN271, on August 16, 2023 from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. I have slightly enhanced the contrast in order to bring out the faint coma. RIGHT: Image (from the LCO facility at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii) of the Centaur Comet 95P/Chiron on May 30, 2021, just three days after it had passed through aphelion. Several galaxies from the cluster Abell 76 are in the image; the brightest are IC 1568 (upper left), IC 1566 (above Chiron), and IC 1565 (lower right).

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 April 29.21 UT, m1 = 13.2, 0.6' coma, DC = 4-5 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

757. COMET CAMARASA-DUSZANOWICZ C/2023 V4 Perihelion: 2024 May 30.36, q = 1.122 AU

Two months have now elapsed since the previous addition to my comet tally, an interval of time which is quite a bit longer than the average such duration I have maintained over the past few decades, although it certainly isn't unheard of, either. During this time one significant event related to Earthrise has taken place: on June 7 former astronaut William Anders passed away -- via a plane crash -- at the age of 90. It was during Anders' only spaceflight, the Apollo 8 mission in late 1968, that he took the famous and iconic "Earthrise" image from lunar orbit that, among many other things, provided a significant part of my inspiration for Earthrise (and, certainly, its logo) and a host of similar efforts around the world over the past half-century.

For these past two months almost all of my visual comet observing efforts have been focused on Comet 13P/Olbers (no. 752), which at this writing has just passed through perihelion and which is presently close to 6th magnitude, and Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS C/2023 A3 (no. 749), which has stagnated in brightness close to 10th magnitude throughout most of this time but for which I remain cautiously optimistic may still put on a respectable show later this year. The other comets that I have had under observation during the recent past are either gone, or at best are in "hiatus" due to being in conjunction with the sun.

This newest addition to my tally was discovered on November 5, 2023 as a result of a collaborative project between astronomers Jordi Camarasa in Spain and Grzegorz Duszanowicz in Sweden, utilizing remotely-controlled telescopes at Duszanowicz's Moonbase South Observatory located at the Hakos Astro Farm in Namibia. The project has produced discoveries of approximately three dozen near-Earth asteroids over the past few years, but this is its first comet discovery. The comet was reported as being about 19th magnitude, and as soon as I saw it posted on the Minor Planet Center's Near-Earth Object Confirmation Page I was able to obtain images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network which showed it as being an obvious comet, already displaying a short but distinct tail. Over the next five days I was able to obtain three additional sets of observations via the LCO network, and the astrometry from all of these early observations was included within the comet's discovery announcement.

Comet Camarasa-Duszanowicz is traveling in a relatively steep direct orbit (inclination 67 degrees). At the time of its discovery it was near opposition and in southern skies near a declination of -49 degrees, and since then it has traveled slowly northward and brightened as it has approached the inner solar system. I continued to image it on an occasional basis via the LCO network, and the last set of images I obtained, in early March 2024 -- after which it became too low in the western sky to access -- suggested it might be bright enough to attempt visually, however here in New Mexico we were having quite a bit of cloudy weather at the time and I was never able to make such an attempt. While it was never quite in conjunction with the sun, it did reach a minimum elongation of 20 degrees in early May, after which it started to become accessible to observers in higher northern latitudes by around the end of that month; according to reports I read and images I've seen from observers in those locations it was apparently near 11th magnitude at the time. I had to wait for the elongation to increase further before I could make any kind of serious attempt, and then after the full moon on June 21 I had to deal with many consecutive nights of rain and cloudy weather. Finally, on the evening of June 28 the skies were somewhat clear albeit with lingering clouds in the northwest, but after some patient waiting I saw that the skies in that region had more-or-less cleared, and although by that time the comet was getting rather low and I had to play a bit of "dodge-the-trees" I successfully detected it. Despite the less-than-ideal conditions I could easily see it, near magnitude 11 1/2 and somewhat condensed.

Images of Comet Camarasa-Duszanowicz I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: November 5, 2023 (approximately 22 hours after the comet's initial discovery), from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. The image has been highly cropped. RIGHT: One of the final images I obtained, on March 10, 2024, from the LCO facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands.

Images of Comet Camarasa-Duszanowicz I have taken via the Las Cumbres Observatory network. LEFT: November 5, 2023 (approximately 22 hours after the comet's initial discovery), from the LCO facility at the South African Astronomical Observatory. The image has been highly cropped. RIGHT: One of the final images I obtained, on March 10, 2024, from the LCO facility at Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands.

The comet is currently on the far side of the sun from Earth and remains there for the rest of its apparition, which keeps it from becoming any kind of prominent object. It is presently located in western Ursa Major at an elongation of 42 degrees, approximately three degrees southeast of the star Omicron Ursae Majoris and -- being now at its farthest north declination of +59.3 degrees -- is traveling almost due eastward at a little over one degree per day. Over the next few weeks it gradually curves towards the southeast, passing three to four degrees south of the "bowl" of the Big Dipper during the latter part of July before crossing into Canes Venatici in early August -- being at that time near its maximum elongation of 50 degrees -- and into Bootes at the end of that month, passing 20 arcminutes southwest of the bright star Arcturus on September 16. Since the comet is now a month past perihelion and is nearest Earth (1.80 AU) on July 4 I suspect it will fade pretty rapidly during the next few weeks, and thus its period of visual detectability will likely be rather short. With the monsoon weather I will likely be experiencing in these parts I will probably, at best, only see it another one or two times.

So now, the year of 2024 which I have for some time in these pages maintained will probably be my last year of sustained visual astronomical observations, is half over. As for comets, I hope to follow Comet 13P/Olbers for another couple of months, and Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS C/2023 A3 for the remainder of the year (excluding the times when it is inaccessible due to being in sunlight). There is one more comet of the "Dependable Dozen" which I have yet to see and which I am hopeful of adding within the next month or so, and one additional comet that I have some reasonable hopes of seeing before the end of the year. As for anything else, we'll have to wait and see, but as more time goes by my physical issues are progressively making it more difficult to maintain active observational activities. For example, on the same night that I added Comet Camarasa-Duszanowicz the recently-discovered near-Earth asteroid 2024 MK was making a very close approach to Earth (0.78 lunar distances) and was an easily-detectable object near 10th magnitude, however there initially were clouds in that part of the sky and, after finishing with the comet, rather than waiting to see if the sky might clear around there I decided I just wasn't up to playing any more "dodge-the-clouds" and instead put the telescope back inside its storage area and began the return to my residence. As I was returning I saw that the sky in the asteroid's location had indeed cleared, but rather than going back and putting the telescope back out -- which I would have done even just a few years ago -- I instead just continued home.

As I have indicated in previous entries, I'm not at all sure what my astronomical activities will look like after the end of this year. I do expect to continue with my imaging activities with LCO (including with the Global Sky Partners network) -- indeed, quite recently I was able to show that a recently-discovered "asteroid" is in fact a short-period comet. There are going to be some changes in my personal life, for example, in a previous entry I mentioned that my partner Vickie and I had decided to get married this summer: that event will be taking place on August 24, less than two months from now. There are also events that may, or may not, take place in the larger world, although I won't speculate about, or comment on them, here at this time. In any event, I can foresee the possibility of some kind of "sea change" taking place in at least some aspects of my life within the not-too-distant future.

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 June 29.19 UT, m1 = 11.5, 2.7' coma, DC = 3 (41 cm reflector, 70x)

758. COMET 154P/BREWINGTON Perihelion: 2024 June 13.28, q = 1.553 AU

At last! I have finally picked up the 12th, and last, of the "Dependable Dozen" comets I identified slightly over a year ago within the context of my push towards my 750th lifetime comet. Since I achieved that milestone earlier this year with three comets of the "Dependable Dozen" still to go the concept is perhaps slightly moot now, but nevertheless it's still satisfying to bring this chapter to a positive conclusion.

The last comet of the "Dependable Dozen" is a short-period object (current period 10.5 years) that I have seen on three previous returns. It was originally discovered in late August 1992 by amateur astronomer, and personal friend, Howard Brewington, then residing east of Cloudcroft, New Mexico -- not all that far from my current residence. I followed it (no. 171) for slightly over a month at that return, saw it again at the subsequent (and relatively unfavorable) return of 2003 (no. 325), then again during the favorable return in 2013 (no. 530). In the entry for that return I discuss its history and well as that of its discoverer in some detail, and as for the comet itself I followed it for slightly under five months as it reached a peak brightness near magnitude 10 1/2.

Comet Brewington was in conjunction with the sun in late February 2024, and since that time has been slowly emerging into the morning sky. The first reported observations were made on June 2 -- when the comet's elongation was 31 degrees -- by Bernd Lutkenhoner and Esteve Cortes utilizing the Slooh Observatory telescope in the Canary Islands, although they subequently reported observations they had made as early as May 25 (when the elongation was 29 degrees). After reading of the comet's recovery I made a visual attempt in mid-June, however I have to contend with trees in that direction, and by the time the comet's location had cleared those trees dawn was quite well advanced and I didn't see anything. During the current dark run I tried again on the morning of July 5 (by which time the elongation had increased to 37 degrees) and although I still had to contend with the trees and early twilight I successfully detected it as a diffuse object near 12th magnitude.

The geometry of the current return is quite similar to that of the discovery return, with this year's perihelion date being only six days later than that in 1992. The comet is currently located in southeastern Perseus some six degrees east of the star Zeta Persei and is traveling slightly northward of due east at 45 arcminutes per day; it crosses into Auriga shortly before mid-July, remaining in that constellation for the next seven weeks -- passing 15 arcminutes south of the open star cluster M38 on July 27 and reaching a peak northern declination of +36.8 degrees on August 19 -- before crossing into Lynx in early September then into Cancer in late October and into Leo just before the end of that month. The comet was near 11th magnitude when it was discovered in 1992 but seems to be a magnitude or so fainter now, and all things considered I expect it will remain somewhat close to its present brightness until perhaps sometime in September before fading beyond visual range shortly thereafter. For what it's worth the comet is closest to Earth (1.76 AU) in early January 2025 and at opposition near the beginning of February, but will almost certainly be far too faint for visual observations by then.

To follow up on Howard's story that I discussed in the entry for this comet's 2013 return, he subsequently retired from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and for the next several years resided in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and for a while was President of the Astronomical Society of Las Cruces; I last saw him when he invited me to speak to that organization a few years ago. He has since relocated to Bastrop, Texas, within the Greater Austin Metro area. As for his comet, its next return, in 2034 (perihelion mid-November), will be the best one since its original discovery; it passes 0.66 AU from Earth and may become as bright as 9th magnitude. Those readers who have been following my own personal story will know that, in all likelihood, I will have ceased visual comet observations well before then, although this could, theoretically, be one of those "briefly-come-out-of-retirement" comets that I have occasionally alluded to; we'll see . . .

INITIAL OBSERVATION: 2024 July 5.45 UT, m1 = 11.8, 1.1' coma, DC = 2-3 (41 cm reflector, 229x; early twilight)

759. COMET 333P/LINEAR Perihelion: 2024 November 29.30, q = 1.113 AU

Over four months have elapsed since my previous tally addition. This is the longest stretch I have gone without adding a comet to my tally since the late 1980s (although it beats by only a couple of days a similarly long stretch I had in mid-2000). There are several reasons for this long stretch, although certainly one significant contributing factor is a lack of comets for which it was worthwhile to make any serious attempts.

There have been some rather dramatic events taking place in my personal life during these past four months. On Saturday, August 24, my long-time partner Vickie and I were married at our residence here in Cloudcroft. We held the wedding outdoors, and the weather was agreeable -- not at all a guarantee, since we are normally still in the later stages of our annual monsoon season here in the southern New Mexico mountains -- and it was attended by various friends, members of her family, and my sons Zachary and Tyler and their respective families, with former "Earthrise Team" member Richard Kestner (who had officiated at Tyler's wedding last year) doing the honors. All in all, a happy occasion . . . As a somewhat symbolic marker of the occasion, that evening I made an observation of Comet 13P/Olbers (no. 752) -- then a moderately bright binocular object of 7th magnitude located near the bright spiral galaxy M64 -- which coincided with the one-year anniversary of my recovery of it.

Vickie and me at our wedding on August 24, 2024, with my sons Tyler and Zachary, my grandchildren Avery, Ethan, and Santiago, my daughter-in-law Sara, and Santiago's mother Karina.

Vickie and me at our wedding on August 24, 2024, with my sons Tyler and Zachary, my grandchildren Avery, Ethan, and Santiago, my daughter-in-law Sara, and Santiago's mother Karina.

A decidedly less pleasant event began taking place in early September when I started experiencing a pain in the left side of my chest, and soon thereafter a drastic shortness of breath. After a week Vickie convinced me to let her take me to the Emergency Room at the regional hospital, but within a couple of days I was transferred to a hospital in El Paso, Texas. I had apparently contracted a bacterial infection in my left lung which flooded my chest cavity with fluid and almost collapsed that lung. I ended up spending three weeks at the hospital, two of those weeks in Intensive Care, and after being confined to a hospital bed for that entire time I lost a lot of strength in my legs and upon discharge was transferred to an assisted nursing/rehabilitation center in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where I would spend another week and a half. I finally arrived back home on Friday, October 18, after being away for over a month. Since that time I have been slowly trying to return to some sense of normality, and although at this writing I'm not entirely back to that yet, I would like to think I've made quite a bit of progress towards that end.

It was during the time I was confined to a hospital bed that Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS C/2023 A3 (no. 749) made its appearance in the morning sky during late September, and I accordingly missed that entire show. According to the images I saw and reports I read from my hospital bed it apparently put on a rather good showing, and all I could do was gnash my teeth in frustration at the show I was missing. Fortunately, by the time the comet made its evening-sky appearance shortly before mid-October I was at the rehab facility in Las Cruces, and on several nights I was able to convince the staff to wheel me out to the parking lot in front of the facility to observe it. (On one night, with assistance from the Astronomical Society of Las Cruces, I was able to arrange a small "comet observing party" for residents and employees of the rehab facility.) While I did have to contend with some light pollution, since the facility is located on the outskirts of Las Cruces' northeast side this wasn't overwhelming. The photograph of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS that I posted in that object's October 15 update is one I took from the facility's parking lot. Meanwhile, since my return home I have been able to follow the comet on a reasonably regular basis as it fades, and at this writing it is near 7th magnitude and still showing a distinct two-degree tail in 10x50 binoculars.

There were a couple of faint comets that I was considering attempting during the September/early October timeframe, but my hospital stay obviously took care of any such plans. Meanwhile, one comet discovered during that time generated a lot of interest: Comet ATLAS C/2024 S1, discovered by the ATLAS program on September 27, and which calculations soon showed was a Kreutz sungrazer. I was actually able to order up a couple of sets of images via the Las Cumbres Observatory network while I was in my hospital bed, and meanwhile some reports, including visual reports from observers in the southern hemisphere (where it was better placed for observation) suggested that it might have been worthwhile to have attempted observations had I been able to do so. At best, though, any such observations would have been quite difficult, and there is no guarantee that I would have been successful.

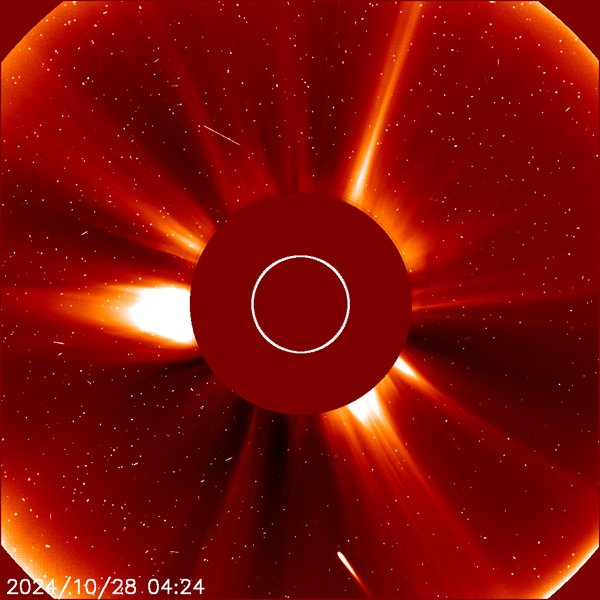

Comet ATLAS passed through perihelion on October 28, and the post-perihelion viewing geometry was such that, while it would have been fairly low in the southeastern morning sky, it would be accessible from the northern hemisphere and conceivably rather spectacular. Unfortunately, it behaved rather erratically as it approached perihelion and showed signs of possible disintegration, including one dramatic outburst to 8th magnitude followed by a rather rapid fading. When the comet entered the field-of-view of the LASCO C3 coronagraph aboard SOHO on the 26th it did so as one of the brighter SOHO sungrazers, and while it was still quite bright when it entered the field of the C2 coronagraph a day and a half later, like all the previous such objects it began to fade, and disappeared entirely within a few hours. Any hopes of a bright cometary display disappeared along with it.

LEFT: Comet ATLAS C/2024 S1 on October 2, 2024, imaged via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. I ordered up this image while confined to my hospital bed. RIGHT: Comet ATLAS in the LASCO C2 coronagraph aboard SOHO on October 28, 2024. Within two hours the comet had begun to fade noticeably. Courtesy NASA/ESA.

LEFT: Comet ATLAS C/2024 S1 on October 2, 2024, imaged via the Las Cumbres Observatory facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. I ordered up this image while confined to my hospital bed. RIGHT: Comet ATLAS in the LASCO C2 coronagraph aboard SOHO on October 28, 2024. Within two hours the comet had begun to fade noticeably. Courtesy NASA/ESA.

The comet that finally ended my long stretch without a tally addition has a rather brief but interesting history. It was originally discovered in November 2007 by the LINEAR program in New Mexico as an apparent asteroid, designated 2007 VA85, that was found to be traveling in a retrograde orbit (inclination 132 degrees); at the time it had the shortest orbital period (8.6 years) of any known solar system object traveling in such an orbit around the sun. (It no longer holds that distinction, although it is still in second place, behind the Apollo-type asteroid (343158) Marsyas which, coincidentally, is currently making a moderately close approach (0.49 AU) to Earth.) It did not exhibit any signs of cometary activity, although it's worth noting that the discovery did not take place until a little over three months after perihelion passage. It was followed until the following June.

On its subsequent return 2007 VA85 was recovered in November 2015. Initially it continued to appear completely asteroidal, however beginning in January 2016 observers began reporting weak cometary activity, necessitating its re-classication (and eventual numbering) as a periodic comet. In mid-February of that year it passed 0.53 AU from Earth, and just before then I picked it up visually (no. 591); initially it appeared as a very faint 15th-magnitude stellar object, but as it approached perihelion in early April it brightened and began to exhibit a faint, diffuse coma, reaching a peak brightness near magnitude 12 1/2.

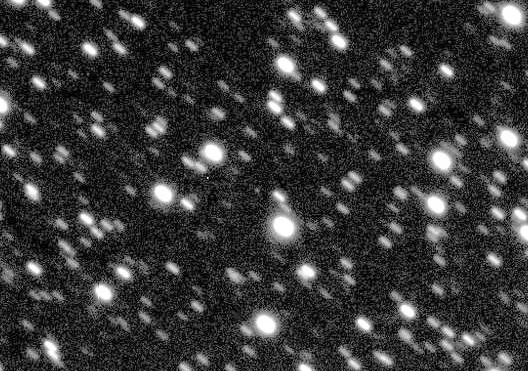

As Comet 333P's current return approached it occurred to me earlier this year that I might be able to make the recovery. On February 29 I submitted an observing request to the Las Cumbres Observatory network, and on a pair of images obtained later that day with one of the 1-meter telescopes at the South African Astronomical Observatory I successfully detected it as a stellar 21st-magnitude object close to the expected position. I was able to obtain confirming images later that same day at the LCO facility at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile and on the following day at SAAO, and all these observations were published by the Minor Planet Center four days later. This is the third periodic comet I have successfully recovered via LCO, following 15P/Finlay in 2021 (no. 702) and 13P/Olbers in 2023 (no. 752); together with the visual recovery I made of Comet 37P/Forbes in 1999 (no. 262) this makes four periodic comets that I have recovered overall.

I continued to image Comet 333P on a semi-regular basis up through late June, during which time it brightened by about a magnitude but remained stellar in appearance. After being in conjunction with the sun two months later it began emerging back into the morning sky in October, and when I imaged it during the middle of that month it had brightened to about 17th magnitude and was beginning to exhibit some weak cometary activity. When I imaged it again at the end of the month it had brightened significantly further and was beginning to display a more typical cometary appearance. While I hadn't quite planned to look for it this early, on the morning of November 6 I had arisen in the morning to observe Comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 (no. 498) -- recently reported to be in a strong outburst, and which I saw near 12th magnitude -- and decided to look for Comet LINEAR which was in the same basic part of the sky, and successfully detected it as a small, very faint object of 14th magnitude that exhibited distinct motion during the half-hour that I followed it.

Las Cumbres Observatory images I have taken of Comet 333P/LINEAR. LEFT: One of the recovery images from February 29, 2024, with a 1-meter telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory. RIGHT: October 31, 2024, from Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands.

Las Cumbres Observatory images I have taken of Comet 333P/LINEAR. LEFT: One of the recovery images from February 29, 2024, with a 1-meter telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory. RIGHT: October 31, 2024, from Teide Observatory in the Canary Islands.

Comet 333P is currently located in central Leo a couple of degrees north-northwest of the star Chi Leonis, and is traveling towards the north-northeast at a present rate of 50 arcminutes per day. Over the next few weeks it accelerates and gradually curves more eastward as it travels through Leo, eastern Ursa Major, Canes Venatici, and back into Ursa Major when it passes half a degree southeast of the star Mizar in the Big Dipper's "handle" on December 6, at which time it will be traveling at slightly over 3 1/2 degrees per day. Two days later it crosses into Draco, and on the following day (December 9) will be closest to Earth (0.54 AU), when it will be traveling at its peak rate of just under four degrees per day. The comet reaches its maximum northerly declination (+66.4 degrees) on December 13 and is in conjunction with the sun (89 degrees north of it) two days later, thereafter becoming primarily an evening-sky object as it begins traveling southeastward through northern Cygnus and then (during the second week of January 2025) Pegasus where it remains for the next few months, being again in conjunction with the sun (32 degrees north of it) in early March.

As for Comet LINEAR's brightness, there is little prior knowledge to go on, especially its post-perihelion behavior. Since it does not appear to be an especially active comet, my guess is that it may peak near 12th magnitude around the time of its closest approach to Earth, and may remain visually accessible until sometime in early January.

I have no expectations of observing Comet 333P on any future returns, but during the forthcoming decades it will continue making occasional moderately close approaches to Earth. It passes 0.58 AU from Earth in February 2042, and in January 2068 it comes to within 0.18 AU of our planet and could perhaps become as bright as 10th magnitude.

As I write these words, I am filled with a significant amount of uncertainty as to how my future activities will unfold after the very near-term future. I have been writing for some time that I would likely "retire" from systematic visual observational activities at the end of this year, and that is now less than two months away. The health problems that I began encountering a couple of months ago, and their aftermath, would seem to be encouraging me to take those plans seriously, and in all honesty, I can't ignore that. Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS and, to a lesser extent, this comet should take me up through the end of the year, and, meanwhile, it is entirely possible that Comet LINEAR could be the last comet I will add to my tally. I have been hoping I could reach at least 760 comets -- a nice round number -- and while there is one comet I know of which has a reasonable possibility of my adding it within the next month and a half, this is definitely not certain. If I do decide to continue on beyond the end of this year at some level, there are some comets coming within the not-too-distant future that should be bright and/or interesting enough for me to make some effort at observing them, but I certainly don't envision any kind of the systematic effort that I have engaged in for the past several decades. In the meantime, I will probably continue with the imaging activities I have been performing via LCO for at least the near-term foreseeable future, and perhaps may still make occasional attempts to recover additional returning periodic comets.